My father does not like to give unsolicited advice, and when I was going off to college, he gave me no warnings about drugs, drinking, or boys.

Article continues after advertisement

He did, however, give me one tip: “Don’t study Latin.” He’d taken Latin in college and had long regretted not learning something more immediately useful, like Spanish. “Learn a language that helps you talk to people,” he advised.

Being an 18-year-old, I ignored him. It turned out to be one of the best decisions I ever made.

For me, studying Latin was less like learning a foreign language—something I’d always struggled with—and more like doing a puzzle.

My first Latin class met at the hangover-friendly hour of 12:15 PM and at the laziness-friendly cadence of three times a week. I’ll admit I chose it in part because I was intimidated by the daily meetings and conversation requirements of most Spanish classes. But within days, I was hooked.

For me, studying Latin was less like learning a foreign language—something I’d always struggled with—and more like doing a puzzle. Unlike in English, the words in a Latin sentence can be in any order—you have to look at the endings of the nouns to understand their function and to piece together the meaning of the whole. I loved the slow, satisfying work of translation, of slotting each word into its proper place until the entire picture was revealed.

My Latin education started with verse: I still love Catullus, famous for his filthy insult poetry, who also wrote beautifully and painfully about grief and unrequited love. But it wasn’t until we moved on to Roman orators and historians that I began to understand what Latin could do for me and my view of the world.

I was a senior in college when I read Cicero’s Pro Caelio, a speech given in 56 BCE defending a man named Marcus Caelius Rufus, who had been accused of a variety of crimes, including murder. The speech is long and convoluted (there’s a reason we waited until senior year to read it), but after a while I began to get the gist: Cicero says that Caelius is innocent, and the real blame for any crimes lies with a woman named Clodia, his ex-lover.

Much of Cicero’s speech revolves around Clodia’s alleged promiscuity—Cicero calls her a meretrix, or prostitute, and insinuates that she is having an affair with her own brother. There’s nothing surprising about a man of any era trying to get another man off the hook by accusing a woman of being slutty. What’s more interesting to me is the way Cicero talks about men.

At one point, Cicero asks how a disreputable woman like Clodia should be punished. “Shall I deal with you severely and strictly and as they would have done in the good old days?” he asks. “Or would you prefer something more indulgent, bland, sophisticated?”

Perhaps, Cicero threatens, “I shall have to call up someone from the dead, one of those old gentlemen bearded not with the modern style of fringe that so titillates her, but with one of those bristly bushes we see on antique statues and portrait-busts.”

The passage aims to stoke a very particular anxiety—that men are no longer real men. They have effete little beards (barbulae) rather than the bushier style their ancestors cultivated. They have grown too modern and sophisticated (urbanus) and lost touch with the rustic (priscus) ways of old. They have forgotten how to deal properly with women.

The conservative desire to return to an earlier heyday—one that is rustic, masculine, and rugged, rather than soft, feminine, and urban—is ancient.

Cicero “hopes his audience will agree with the view that the bearded past was a more moral era than the present,” Judith Hallett, a professor emerita of classics at the University of Maryland, told me in an email. He wasn’t alone in evoking a tougher, beardier era: the elder Cato, a Roman historian who lived from 234–149 BCE, “also employs this rhetorical strategy in evoking a past where women were put in their place,” Hallett said.

Ever since I read the Pro Caelio, though, I think about it all the time. I thought about it when Sarah Palin praised the virtues of “real Americans” in the rural heartland. I think about it now when Trump and other Republicans promise to Make America Great Again, and to return the country to a time when men worked manufacturing jobs and women stayed home.

The conservative desire to return to an earlier heyday—one that is rustic, masculine, and rugged, rather than soft, feminine, and urban—is ancient. It’s so ancient that even the ancients talked about it—even in 56 BCE, apparently, men had already been ruined by modernity.

Studying Latin taught me that contemporary anxieties about manliness and cosmopolitanism date back thousands of years. More than that, it taught me that the idea of a previous Golden Age is just that—an idea, something politicians and orators use to paint some people or groups as original, unsullied, and good, and others as intruding or corrupting influences. I probably could have learned this lesson from history, but I don’t know if I would have understood it as deeply if I hadn’t read it in its ancient, priscus form.

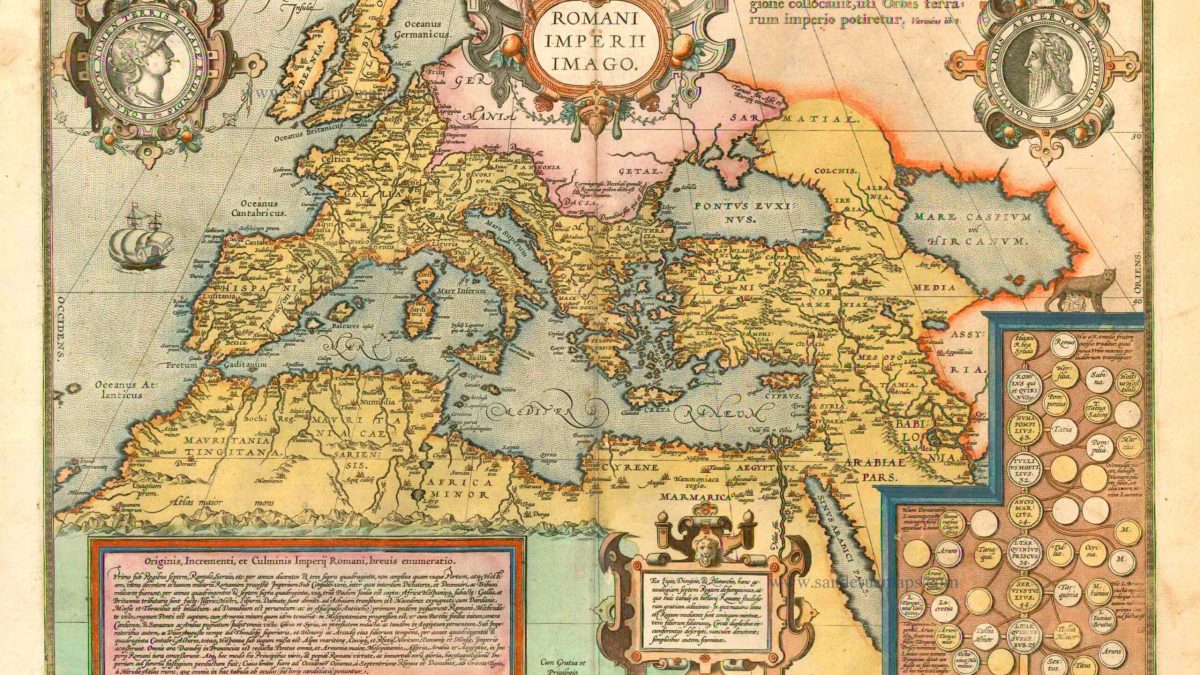

Today, the Latin language, along with Greek and Roman iconography more generally, is often co-opted by white supremacists who claim that they—and not immigrants or people of color—are the true descendants of an intellectually and aesthetically superior race. But the Romans weren’t superior to us; if anything, reading their words should remind us that they were exactly as insecure and anxious as we are, and that ascribing a mythic superiority to the past is an age-old political and rhetorical tactic, nothing more. (Incidentally, the Romans also would not have understood themselves as white.)

I find it moving that the beauty and humor of Latin literature endures, thousands of years after its writing.

Years after my first Latin class, I still think about the Roman Empire almost daily. It’s not just the foibles and prejudices of the Romans that intrigue me; I still love the way Catullus writes about yearning (“my tongue is numbed, a keen-edged flame spreads through my limbs”) and the way Livy wryly reports competing accounts of the story of Romulus and Remus (some say they were reared by a wolf, while others say they were merely raised by a woman who was sometimes called a she-wolf as an insult). I find it moving that the beauty and humor of Latin literature endures, thousands of years after its writing; it gives me hope that maybe the best of our civilization will survive as well, and that our memory will be a source of joy and not just a cautionary tale.

My dad was right about one thing: I do regret not studying a living language in college and beyond. If I’d stuck with Spanish after high school, I know I’d be a better neighbor, a better journalist, and a better resident of my city and of the world. I plan to encourage my children to become fluent in a living language other than English—but I might advise them to take Latin, too.

I want them to understand the patterns of history and to be skeptical of the arguments of the powerful, something my Latin classes taught me. And I want them to understand that what we do and say now can matter, not just today, but thousands of years from now, in ways we cannot begin to imagine.

__________________________________

Bog Queen by Anna North is available from Bloomsbury Publishing.