As soon as I read the newspaper account of the Nagamo Trail Murder in January 2019, I knew that I wanted to write about it. I’d been spending summers in northern Minnesota for more than a decade. At least once a week, my partner and I rode our bikes on the Nagamo Trail looking for eagles, foxes, and loons near the place where teenagers Micah Waldon and Brittney Moran walked Brandon Halbach into the freezing-cold woods around 3 a.m. on a January morning and shot him at close range in the face.

Article continues after advertisement

I knew the world of the eagles and loons pretty well but I didn’t know the world of the kids.

Thinking about it, I realized that nobody did. I couldn’t think of any representations of the lives of young people in this forlorn and isolate place on TV or in print. The Iron Range of northern Minnesota, where this crime took place, was a traditional bastion of Democrat values but in 2016 an overwhelming majority of voters in the northern counties flipped their party allegiance and voted for Trump.

I’d read Truman Capote’s 1966 non-fiction novel In Cold Blood in the 1970s and the first thing I did in early 2019 was read it again.

The journalists followed, arriving for two or three days at a time to research think pieces about life in the northern Midwest, a region that has been known since the Reagan 1980s as America’s Rust Belt. Their reports showed us statistics and photos of boarded-up stores on the main streets, but they didn’t offer much clue about the texture of life in the region, what it might actually be like to grow up and live there.

I’d read Truman Capote’s 1966 non-fiction novel In Cold Blood in the 1970s and the first thing I did in early 2019 was read it again. Capote brilliantly captured those novelistic qualities—the faces, the houses, the rhythms of speech—in his depiction of mid-20th century rural Kansas and it was rightly considered one of the great books of its time.

When a prosperous farming family was murdered in their own home in cold blood for no reason at all by two young male ex-cons, the image of a neat, safe, mid-20th century rural American life was shattered. Clearly, there was a dark, nihilistic underside to the culture. As one of the killers remarked to Capote about his victim. “I thought he was a very nice gentleman. Soft spoken. I thought so right up until the moment I cut his throat.”

Norman Mailer achieved a similar thing in his non-fiction novel about Gary Gilmore The Executioner’s Song—although, by the time the book was published in 1979, the seedy, psychotic world of Gilmore and his two girlfriends, Nicole and April Baker, hardly came as a revelation.

Rather, Mailer’s recordings of them felt like an extreme but iconic depiction of 1970s countercultural underclass Americana, where teenage girls are drugged and gang-raped without registering much on the surface at all. When Gilmore famously said, “Let’s do it,” just before he was hooded and shot by a firing squad, it was as if he’d summed up the nihilism and apathy of an entire era.

The best true crime stories act as ports of entry to entire communities. By unraveling the events of the crime, we come to know not just the victims and perpetrators but their friends and families, the police, the public defenders, and the prosecutors.

When I started researching The Four Spent the Day Together, Micah Waldon, Brittney Moran, and their friend and accomplice Evan Stanton were already in prison. I reached out to the three of them right away. Micah asked me to talk with his mom Crystal King instead. I rented an office on the main street of Harding, MN and hired a research assistant who’d just graduated from Harding High School.

Cameron Lusk, who’d just turned eighteen, was the same age as Brittney and Micah. Luckily, she knew everyone and she was respected and liked by the entire town. As a favor to her, many of Micah and Brittney’s old friends and classmates stopped by the office to answer my questions.

In a small town like Harding, a crime involving local children of local families shatters the relatively placid and usually numb routines of daily life. Everyone has an opinion.

But there was a gap between us—our culture, our language, our understandings. My heartfelt and searching questions elicited very short replies: I don’t know… I can’t remember… He was quiet… She was a liar… Maybe he was shy. Even though abortion remains legal in Minnesota and there was a Planned Parenthood office nearby in Duluth, in Harding, among these respondents, a teen pregnancy automatically equaled teen parenthood.

I’d partly grown up in Milford, Connecticut—a small blue-collar American town not very different from Harding—and I thought that perhaps I could access the world of the kids by traveling back to my own troubled adolescence. But our worlds were too different. The best I could do was to hang around Harding and listen.

In a small town like Harding, a crime involving local children of local families shatters the relatively placid and usually numb routines of daily life. Everyone has an opinion. I turned to the social media pages of Micah, Brittney, Brandon, and Evan’s friends in search of more candid remarks. I looked at the notorious MN News and Gossip Facebook page that thrived at the time, where friends and neighbors competed to better trash and malign the kids and their families.

During our prison visits and email writing, I learned that Evan Stanton’s father was homeless and his mom was in prison for selling the six-year-old Evan and two of his siblings into child prostitution. Evan had been in foster care and intermittently homeless for most of his 21-year-old life. I tracked down his father in a motel for the homeless and recorded his trajectory from jail to prison to jail on petty, addiction-related offenses between two states in the northern Midwest. In an early draft of the novel, I wrote an account of Bob Stanton’s life using his language and thoughts in a free indirect style… but my friends found it incomprehensibly numb and boring.

For each of the three offenders, I discovered dozens of mitigating circumstances that explained how they came to be there. But at the same time, none of these mitigating circumstances changed the fact that they’d killed Brandon Halbach, cut short his one-day-short-of-34-year-old life and broken the hearts of his friends, child, and family.

I don’t think I’ll ever understand what happened during the day those four young people spent together, or that anyone will. But in the tradition of the true-crime genre, researching the murder opened a door onto life in what geographer Phil A. Neel calls “the hinterland,” and the extreme bifurcation between those who will leave and those with unclaimed futures who will be left behind.

__________________________________

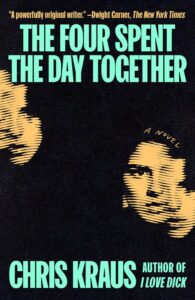

The Four Spent the Day Together by Chris Kraus is available from Scribner, a division of Simon and Schuster.