With 881,000 people living in less than 47 square miles, San Francisco packs a tremendous amount of wealth and cultural influence into a fiercely unequal city. San Francisco is far smaller than Los Angeles, New York, London, or any of the Chinese metropolises where technological devices are manufactured. It’s smaller than Charlotte, North Carolina and Jacksonville, Florida. Its politics tend to be a battle between center-left and progressive factions, subsidized by the stratospheric wealth of policy-shaping tech and real-estate billionaires.

Article continues after advertisement

Although San Francisco was the inheritor of a distinctly American brand of social liberalism, tech elites were countercultural (in the sense that the more conservative ones cast their politics as a rebellion against the woke mainstream). Under this pretense, wearing a MAGA hat in a Google office or entertaining eugenicist ideas about race and intelligence was a way of daring to go where liberals feared to tread. “The most rebellious thing you can be in San Francisco is a Republican,” wrote Elon Musk.

A venture capitalist who ran the prized startup incubator Y Combinator, Garry Tan had used his wealth and professional network to become a San Francisco political power broker, helping to drag the local Democratic party to the right, pouring hundreds of thousands of dollars into the recall of school board members, the recall of district attorney Chesa Boudin, and campaigns benefiting conservative Democrats. On social media, Tan was pugilistic to the point of belligerence, casting his political enemies as corrupt malefactors responsible for the despoliation of his beloved city. He sat on the board of GrowSF, a tech-funded advocacy group with an associated PAC that could make it rain for like-minded politicians.

As the home of the tech industry and the battleground over the perceived failures of Democratic urban governance, San Francisco became a hotbed of elite resentment.

Late one night in January 2024, Tan had some drinks and went on a tirade on X against seven city supervisors, calling them out by name, writing, “Die slow motherfuckers.” It turned out that Tan was quoting a Tupac Shakur line, but the sentiment was clear. Tan apologized the next day and asked to be held accountable. Five of the supervisors received death threats in the mail at their home addresses. The mailed threats read, “Garry Tan is right! I wish a slow and painful death for you and your loved ones.” The mailer included an image of Tan’s post. The supervisors filed police reports. Tan’s supporters said that he couldn’t possibly be blamed for the threats. Tan hired a new spokesperson and was profiled in the New York Times as a local political influencer whose civic passions sometimes got the best of him. In short order, he returned to posting with pretty much the same fury as before, without the semi-explicit death threats.

One spring day, Tan’s critical gaze landed on the work of freelance journalist Gil Duran, a tech-industry muckraker with a background in Democratic politics who was starting to take very seriously the right-wing political ambitions of San Francisco tech moguls. Duran had published articles on Tan and his wealthy colleagues, like Balaji Srinivasan, a tech investor who was promoting an esoteric but stubbornly influential concept called the Network State. Drawing on the anti-state and corporate charter city ideas then coming into vogue, the Network State described a potential “tech Zionism” in which right-wing techies (“Grays”) would buy property, take over local institutions, and cleanse neighborhoods of their ideological opponents (“Blues”). Grays were generally intellectual tech elites who would reap the fruits of technological progress. Blues, who included woke Luddites and other political enemies, would be shut out of the bounty—forced out, in fact. It sounded like an intentionally dystopian mash-up of corporatist and colonialist ideas. Srinivasan’s Network State—and its core idea of capturing or creating parallel, anti-democratic institutions—was attracting adherents on the tech right.

As Duran’s work began to circulate more, Tan, writing on X, asked: who was paying this guy? The writer Susan Dyer Reynolds suggested—through a circuitous series of connections that defied space and time—that Duran was being paid by George Soros. “Interesting,” replied Tan, who had called Duran a “parasite,” “pathetic,” and “an unserious clickbait blogger.”

On X and his blog, Srinivasan speculated about who must be funding a freelance journalist who had the temerity to question the political program being promoted by powerful tech leaders. The chart he devised was covered in slashing arrows that created an impression of a vast web of influence and money underwriting Duran.

The suggestion that someone was secretly paying Duran was hilarious to anyone with a cursory familiarity with the attenuated state of the journalism industry. Duran had provoked the VC class’s ire for good reason, but he was not exactly splashing features on the front page of the New York Times. His work appeared in the New Republic (to which I have also contributed), the San Francisco Chronicle, and his own newsletter, which he had cheekily named The Nerd Reich. There was little money in this kind of work, only the satisfaction of uncovering information that powerful people didn’t want the public to know. And maybe pricking their egos in the process. As Duran admitted to me at the time, his newsletter had three paid subscribers. (His fortunes have since improved.)

We do live in a culture where little escapes the cold logic of the market. For the ultra-wealthy, pretty much anything could be acquired for a price; their worlds were anointed to their specifications. If a relatively unknown freelance journalist was suddenly intruding on their good time, perhaps someone had put him up to it. Yet suspicious as it might have been to some, Duran was publishing articles about the authoritarian designs of tech VCs just because he thought it was information the public should know. The irony was that someone in this situation was getting paid to spread skewed political narratives. As mentioned previously, Susan Dyer Reynolds, the journalist who had posted about a misconceived connection between Duran and George Soros (there was none), was being paid by some of Tan’s political allies via a GoFundMe launched by venture capitalist Jason Calacanis while also receiving funds from Neighbors for a Better San Francisco.

Duran had bigger concerns than who might be paying a local blogger. He was focused on Srinivasan and his role as the promulgator of the Network State ideology, which dovetailed with other right-wing libertarian tech movements that sought to claim land and political sovereignty for tech elites. “It is very much a right-wing ideology, but not exactly Republican,” said Duran.

The ideology was corporatist, with the startup as the platonic economic-political formation, which made startup founders herculean figures. It was dismissive of a political culture that seemed obsessed with wokeness and against tech’s unrepentant pursuit of innovation and profit. It had a sense of religiosity, but God had been dethroned by AI—or at least by the promise of creating Artificial General Intelligence, also known as AGI, a greater-than-human intelligence that many seemed to think was only months or years away from emerging. AGI would change everything—many industry leaders openly talked about it somehow saving humanity or bringing about the end of the world. If an all-powerful AGI saw humans as an impediment to its own flourishing, it might kill us all. Whether any of this was even possible didn’t matter. Venture capitalists and AI company executives controlling billions of dollars and vast, resource-guzzling data centers had convinced themselves of it. Some called AGI “the last invention,” which would fix all problems facing humanity.

Duran described this belief system as a logical terminus for a group of coddled men possessing limitless money mixed with limitless self-regard. “They’ve kind of reached a point where they have so much wealth, and so much egomania—and, in some cases, so much drug-addled thinking—that they decide they’re going to rule the world, and that democracy is an outdated form of software,” he said.

“They think that because they have an algorithm and an app, they can be the rulers of the world,” San Francisco supervisor Aaron Peskin told the New York Times. “Good luck with that.” Peskin would become a top electoral target for San Francisco’s tech elites in the 2024 election cycle.

For Duran, this rising tech authoritarianism wasn’t a passing political fad but the culmination of shifts in wealth distribution, political power, and the computerization of society that had been decades in the making.

“These people have enough money to be dumb and dangerous for a very long time,” he said. “They have to start finding ways to seize territory and power and create a different world that doesn’t look anything like the United States we have today. I think what we’re seeing here in San Francisco politics is like the emergence of that strategy.”

In the 2024 election, Silicon Valley’s boutique tech-fascist ideologies found themselves in convenient alignment with Donald Trump and the Republican Party. They shared the politics of resentment, a sense of elitism masquerading as populism, and disgust for the Democratic Party. They didn’t like taxes or the government interfering in their corporate affairs. As Trump surrounded himself with VCs and tech executives, he began preaching the virtues of Bitcoin and echoing their talking points on AI policy. He gave the keynote speech at the country’s biggest Bitcoin event, promising to fire SEC chair Gary Gensler and to establish a national strategic Bitcoin stockpile. He had dinner at the palatial San Francisco home of David Sacks and, impressed by Sacks’ portfolio, listened as a roomful of centi-millionaires and billionaires urged him to name JD Vance, a venture capitalist and Peter Tiel disciple, to be his vice presidential running mate. North Dakota governor Doug Burgum, a software mogul and VP contender who was also in attendance, could only look on as his name went unmentioned.

Some of the tech leaders presented themselves as moderates, but they politicked and spoke like right-wing reactionaries, especially on social media.

As the home of the tech industry and the battleground over the perceived failures of Democratic urban governance, San Francisco became a hotbed of elite resentment and an unlikely source of cash for the Trump campaign. The city’s dwindling middle and working classes blamed tech millionaires and billionaires for pricing them out of a once-vibrant city and promoting regressive policies on homelessness and criminal justice. Millionaires and billionaires in turn blamed progressives for making it difcult to build housing and turning the city into a supposedly lawless zone of violent crime, public drug use, and social disorder. Tech elites proposed tried-and-failed punitive strategies to address homelessness (bans on outdoor camping) and drug use (arrests, incarceration, forced treatment). The left tended to emphasize a housing-first policy that prioritized finding shelter for homeless people. Tech elites thought this rewarded drug use and irresponsible personal behavior.

The two sides were not quite irreconcilable. Garry Tan told a reporter that he’d had a rewarding meeting with one of the supervisors whom he threatened in his infamous X post. But that gesture toward detente seemed unlikely to stem the very real anger expressed by Tan and his colleagues. Tan and his political opponents were at odds for good reason. They had vastly different ideas about the causes and solutions to San Francisco’s problems. They disagreed about who should wield power and the management of the city’s limited resources. These were classic political differences, but they had been amplified on the social-media stage. As a wealthy, well-connected political player with a large audience, Garry Tan was key to this new dynamic.

“There’s a deep polarization taking place, and the tech people with all their money are throwing a lot of gasoline on the fire, to try to move everybody’s politics toward the right,” said Duran. “And to pretend that they have solutions to the problems.”

Some of the tech leaders presented themselves as moderates, but they politicked and spoke like right-wing reactionaries, especially on social media. Tan referred to himself as a moderate or centrist.

Elon Musk adopted the same label. In March 2024, Musk posted on X what sounded like a declaration of war.

This is a battle to the death with the anti-civilizational woke mind virus.

My positions are centrist:

Secure borders

Safe & clean cities

Don’t bankrupt America with spending

Racism against any race is wrong

No sterilization below age of consent

Is this right-wing?

Musk also seemed to refuse to interrogate his own political positions. In another post, he seemed baffled that people might have problems with Alternative for Germany, or AfD, the far-right, deeply anti-immigrant German political party that was the closest thing the country had had to a Nazi party since 1945.

“Why is there such a negative reaction from some about AfD?” Musk asked Naomi Seibt, a right-wing German activist and influencer in her early twenties. “They keep saying ‘far right’, but the policies of AfD that I’ve read about don’t sound extremist. Maybe I’m missing something.” (Seibt worked as a paid spokesperson for an anti-climate science campaign launched by the libertarian Heartland Institute.)

Musk would become a vocal supporter of the AfD—to the point where he was denounced for electoral interference by Chancellor Olaf Scholz. In the run-up to the February 2025 national elections, Musk appeared via video at an AfD rally and urged Germans to move beyond “past guilt” and to vote AfD to protect their civilization from outside invaders. AfD finished second, the best result for a far-right German political party since the Nazis came to power.

__________________________________

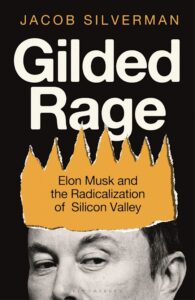

Excerpted from Gilded Rage: Elon Musk and the Radicalization of Silicon Valley by Jacob Silverman. Run with permission of the author, courtesy of Bloomsbury Continuum, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. Copyright © Jacob Silverman, 2025.