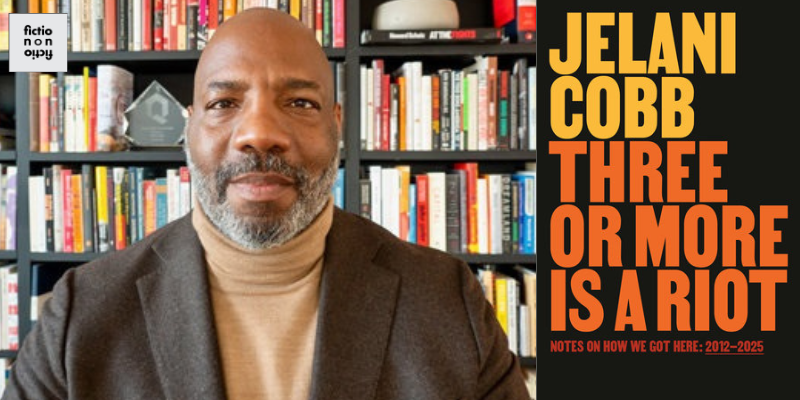

New Yorker staff writer Jelani Cobb joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his new essay collection, Three or More is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here: 2012-2025. Cobb recalls how he began the project by trying to understand how George Zimmerman’s killing of unarmed black teenager Trayvon Martin in 2012 set the tone for the era to come. Cobb considers how history’s exceptions skew narratives, so that writers miss the bigger picture. He reflects on how discourse about race shifted between the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations and considers the juxtaposition of Martin’s murder with Obama’s presidency. Cobb also speaks on the significance of transparency in journalism, calling for reporters to show their work to reinforce public trust. He explains his preference for a lowercase “b” in “black” as a racial term, given that the word is not a proper noun, does not designate a nationality, and that capitalization may perpetuate inaccurate racial ideologies. Cobb reads from Three or More Is a Riot.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/ This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, and Bri Wilson, Emma Baxley, Hope Wampler, and Elly Meman.

Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here: 2012-2025 • The Matter of Black Lives: Writing from The New Yorker, edited with David Remnick • The Essential Kerner Commission Report, edited with Matthew Guariglia • The Substance of Hope: Barack Obama and the Paradox of Progress • The Devil and Dave Chappelle and Other Essays • To the Break of Dawn: A Freestyle on the Hip Hop Aesthetic • “Lessons of Later-in-Life Fatherhood” | The New Yorker, June 14, 2025 • Full text of Jelani Cobb’s 2025 Reuters Memorial Lecture: Trust Issues. Credibility, Credulity and Journalism in a Time of Crisis

Others:

Lincoln • Django Unchained • Gwen Ifill

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH JELANI COBB

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Another thing that’s really fundamental to the structure of the book is that it’s a chronologically ordered set of comments and essays and many of them have the postscripts or annotations at the end of them from the Jelani Cobb of now revisiting the work and annotating. There’s an essay about Black Panther and then an annotation that refers to the sequel, which appeared after his untimely death, and the diamond company De Beers getting Lupita Nyong’o as an ambassador and so they’re taking up space at the premiere of the sequel. Or you wrote an essay about Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln and you reassess your original criticism of the film. There’s a lot of cultural commentary in here and political commentary, and, often, the intersection of those two things, and then these revisitations. Can you talk about your approach to not only curating but reassessing your own work, and how important that was to your overall process? We’ve had guests on the show who talk about collections of their body of work and we’ve had people say “I would never, ever look at my stuff again. I hate it.” How was it for you?

Jelani Cobb: It’s very difficult. There are a couple of things that I don’t like to do. One is that I hate to hear the sound of my own recorded voice. A lot of people feel that way. I really, absolutely hate to see myself on video, and I don’t like retracing my steps through something I wrote. But I did it for this because I thought it was important to be honest and to actually say “I missed this. I thought that this was blue, but it turned out to be red. I thought that this was up, but it really was down.” And in some way, once I got into doing that, it was freeing to just walk through and say “Yep, this is what I thought then and I think it’s an accurate assessment of what was going on.” You get to understand what your batting average was like at a particular time.

I feel on some level, all writing is memoir. I wasn’t writing about myself and I’m allergic to writing about myself, although I did write for The New Yorker, a piece that we didn’t include because it really didn’t fit with the theme of the work, but I wrote a long piece about fatherhood, and it’s deeply personal about my own experience as a father, and about my relationship to my own father. But I wrote that after 13 years at The New Yorker. So I said, “Talk to me in 2038. I’ll write something else personal.” But these pieces were implicitly autobiographical because they represented my thinking at a particular time and my analysis. Often, like the pieces about Ferguson, I was writing as I was processing; there was still stuff on fire as I was sending out copy. It is good sometimes, once the ashes have stopped smoldering, it’s good to revisit that and say, “Well, what does this really look like? And what did you know? What did this turn out to be?

Whitney Terrell: One of the repeating themes that I noticed is this idea that you mentioned, speaking in one of those parts where you’re revisiting the Lincoln movie, where you say “history is too often skewed to the exception.” I feel like you keep coming back to that. You talk about it in terms of Django Unchained, the Tarantino movie, you talk about it in terms of the movie Lincoln itself. I wondered if you could just talk about that idea as it reappears through the essays.

JC: I picked that up in undergrad in a historiography class taught by a professor—I’m going to blank on this woman’s name, which I should have had tattooed on my arm, because she was so influential—but this professor pointed out the way that we look at exceptional things, which is great. If you are walking down the street in Manhattan, and you see someone in an Abraham Lincoln-style top hat, you’re going to notice that person. Well, maybe not in New York. In New York, anything could be anything. But if you were walking down the street in most parts of this country and you saw someone with a Lincoln-esque top hat on, you would stop and notice that person because they’re not dressed the way everyone else is.

But what that does is cause you to overlook the fact that there have been 12 people who’ve walked by you wearing navy blue sweaters. And what is that about? Has there been a run on navy blue sweaters? Was this a plan by some clothing manufacturer that said “navy blue, we’re going to push navy blue this year,” or burnt orange, or whatever color it is that people have, but because it’s so commonplace, you don’t notice it? But the fact that it’s commonplace also means that it’s important. The famous example is that we have a ton of books about the invention of the automobile and the way that it changed lives, and very few books, comparatively, about the fact that humans rode horses for two or three millennia before that and how incredibly durable that relationship was. How did we manage to adapt our lives to this equestrian mode of transportation over all of this human history?

So when we think about Lincoln and his exceptionality, which is unquestionable and intriguing and fascinating, there are ten different reasons to be enamored or at least intrigued by Abraham Lincoln. Does his exceptionalism get in the way of us understanding the 19th century and where the average person was at that time? I think it does. That’s deeply convenient. Lincoln—whom I deeply admire although not for the reasons, I think, that most people deeply admire him—Lincoln allows Americans to focus on the way that slavery ended, as opposed to the extent to which it had persisted for nearly two centuries at the point of Lincoln’s decisive proclamation.

VVG: You’re talking about not only exceptionalism in terms of character, but also exceptionalism in terms of time. How our fixation on these particular moments helps us to escape from the question of what people are doing in between them.

JC: That’s exactly it. It’s like the John Lennon lyric, “Life is what happens while you’re making other plans” or somesuch. I would hazard a guess that if you talked to 50 couples who have been happily married for 30 years or more, and you ask them about their marriage, I’m going to bet that no more than three of them are going to talk about the wedding. The wedding is the big ceremony. It’s this incredible day. We had photography, we got this, we got that. That’s not what the marriage is.

Or if we think about graduation, if we talk about the most important things that we experienced in college, graduation probably wasn’t one of them. It’s like sleight of hand. “Pay attention to what’s happening here,” and that blinds us to these other subtle kinds of shifts, and these things that are equally or probably even significantly more important that happen gradually or happen slowly, or they happen in the quiet moments in between the big punctuations. I also think for writers, there’s a lot to be mined in those moments.

WT: Trying to cover up the real history of what slavery was seems to be a project for some people in this country, rather than something to be avoided, and particularly for this current administration. But I want to move on to the middle part of the book. The Winter in America section has a eulogy for Gwen Ifill who you describe as “a standard bearer for journalism, a mentor to young reporters and a profoundly decent colleague.” You write about the particular cruelty of her death at a time when her personal and professional qualities were most needed. You’re the dean of the most important journalism school in the country. Could you talk about how journalism has changed in the nine years since Ifill’’s death, and does the loss of a journalistic beacon mark a turning point for you in the trajectory of the media?

JC: Gwen Ifill was an embodiment of the virtues that we try to instill in the journalism school. She was open-minded, she was thoughtful, she would ask tough questions. She was deeply invested in the ethical mandates of our profession. And her loss came at a moment where I was counting the troops, almost, because we’re in this battle for the preservation of democracy, for the preservation of civic life in this country, to sustain our mission and our role as the fourth estate. I habitually think about the people who I think are exemplars, who I think are the best people at this and her loss represented that. And we’re still in this battle. We’re still in a moment where people think that we’re the enemy of the people, or that we’re “fake news,” or that we go to our offices and just make up things and hit publish and send it out into the world. And that was what I was thinking about at that moment nearly a decade later, that’s still what I think about when I think about Gwen. Or very often, it goes in the opposite direction. I think about the battles that we’re fighting in journalism, and then I think about Gwen.

WT: I do want to ask you one specific thing that I’ve been thinking about a lot. I consume a lot of my news on YouTube now through channels like The Bulwark, for instance, or places that I consider pro-democracy. But you can go on YouTube, start a YouTube channel and just make things up, make things up about people, make things up about political figures, make things up about tragedies, make things up about the French president’s wife, and create money for yourself. It increases your following to lie and to spread disinformation. There are incentives that are there that would not have existed at a time when you had to go through a gatekeeper of some kind like an editor at a publication who doesn’t want to lie. How is journalism going to get past this issue?

JC: I have a potential solution for this. I’m ready for it. I’ve been making this argument. I gave a speech last spring at Oxford, the Reuters Memorial Lecture, and in it, I said, we have a crisis of credibility in that people don’t trust the news. At the same time, we have a crisis of credulity, because people do trust other people who are not the news, who absolutely do not warrant the faith that the public places in them, or some portion of the public places in them. My solution to that was for everyone to show their work, or at least for the public to demand that everyone show their work. For journalists, when we produce a story, if this is a digital print story, it should have a hyperlink that says “How I reported this story: I got a tip that sent me to follow a Freedom of Information Act request with this agency which gave me these documents, which caused me to call this Congressperson and ask these questions. The entire conversation is here. You can listen to the audio, and that sent me to this regulatory agency, and I found that there are these toxic chemicals that are in this playground.” All of that stuff, we should put it in the foreground.

Where people are saying, “How do we regain the trust of the public?” We don’t. We just ask the public to distrust equally. Therefore, when a person, a charlatan, tries to sell you a conspiracy theory or tries to whip up your anger and contempt at some religious group or some ethnic group, be skeptical of them too, and ask, “How do you know that? Where did that come from? You show me your work.” And the advantage for journalism, at least for good journalism, is that we can show our work and our counterparts really cannot. I think that’s the best we can hope for.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy.