At 9:39 PM on February 15, 1898, Clara Harlowe Barton was one minute away from a moment that would change her nation forever. That Tuesday night, she sat at her desk at Havana’s Hotel Inglaterra, plying through the pleas for relief in the world’s newest abattoir. Her seventeen-year-old American National Red Cross had just come home from aiding Turkey’s beleaguered Armenians; now stories of “starving Cuba” filled the news. Revolution pummeled the island for the third time since 1868; in order to starve out rebels, the Spanish Crown drove peasants into “concentration camps” and burned their farms. During eighteen months in 1896 and 1897, more than 225,000 reconcentrados died from disease and starvation. The Red Cross put the death toll closer to 425,000.

Article continues after advertisement

That Christmas, Barton had turned seventy-six. She still toured disasters the way high society toured the Wonders of the World. Since the Civil War, relief efforts had taken her to wars, floods, fires, famines, cyclones, and earthquakes. The world revered the straight-spined spinster in the black dress who stood five feet tall; she focused disaster in her bright black eyes and saved lives. But miracles have a cost, and after each occasion she’d collapse and dream of death, its eventual release “the sweetest hour in my whole existence.”

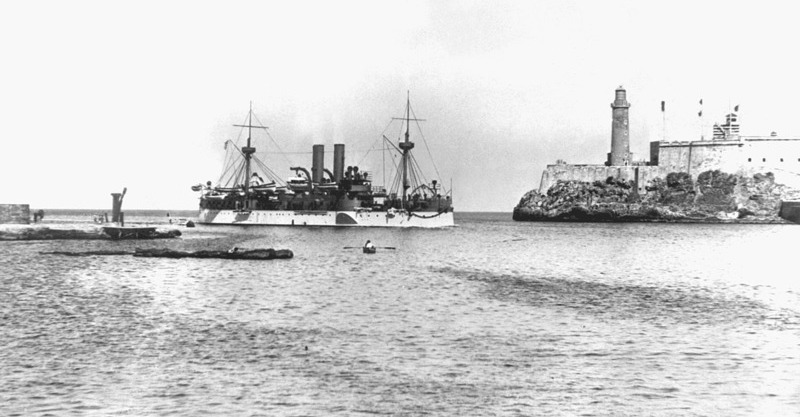

She’d been in Havana six days. On February 9 she’d visited the Palace of the Governor and paid her respects, then boarded the sleek white USS Maine. The solemn, bespectacled Captain Charles Sigsbee squired her around his twenty-four-gun battleship—the soaring bridges connecting three deckhouses, black-painted guns, gilded bow. Sailors in dress whites stood at attention like dolls. The ship had anchored in the harbor as a “friendly act of courtesy” to Spain, but U.S. Consul General Fitzhugh Lee believed she could protect American lives and property in this war-torn land. Away from the ship, Barton was spending much of her time in a warehouse called Los Fosos, four long buildings housing hundreds of reconcentrados who were dying so quickly their graves went unnamed. A “grim, terrible pile of black coffins” stood guard at each entrance; inside, she faced “death-pallid mothers lying with glazing eyes.”

If Cuba’s liberation created for Americans a vision of themselves as emancipators, the Philippine “liberation” turned so savage that the public shut it out of mind.

At least for the moment, she enjoyed a brief lull. The hotel was still, one of those colonial donjons lush with tropical flowers, a fountain, and gardens. Her window peered south toward a dark sea. To the right lay the harbor, its narrow entrance guarded by the grim Morro Castle. At nine PM she’d heard the melancholy strains of Taps, no doubt from the Maine.

How many times had she heard a bugle play that beautiful, sad tune?

*

Afterward, many recalled their exact location at 9:39 PM. At the redbrick German Hospital in Newark, New Jersey, twenty-one-year-old Clara Louise Maass had just been promoted to head nurse; she supervised the student nurses, who lived in shoebox rooms in the colonnaded Trefz Hall. Three years earlier she’d been like them: rising at 5:30 AM, leaving the wards fifteen and a half hours later. Hard work, but an honor, for in 1890 the United States boasted only thirty-five nursing schools with a mere 471 graduates; this, at a time when doctors realized that the two greatest life-saving advances in medicine over the past thirty years had been aseptic surgery and trained nursing. Maass traced her rounds, dressed in crisp blue-and-white stripes, white muslin cap with a black ribbon, thermometer pushed through a buttonhole. This was her uniform—the army of her heroes Florence Nightingale and Clara Barton.

In tiny Iola, Kansas, thirty-two-year-old Frederick N. Funston signed on the dotted line. From August 16, 1896, to January 10, 1898, the five-foot-four-inch congressman’s son had fought in the same conflict Barton now tried to relieve. In his eighteen months combating the Spanish imperial army, he’d survived seventeen battles; had seventeen horses shot from under him; been wounded in both lungs, an arm, and a hip; and contracted malaria. When he returned to New York, he weighed two-thirds of his normal 120 pounds and coughed up blood. The next morning, he’d hop the Kansas City Express to formalize a three-and-a-half-month lecture contract with the theatrical manager J. A. Young. The “little fellow” who’d soon become one of turn-of-the-century America’s most controversial characters had decided to mount the stage.

Within sixty seconds, events were set in motion turning two strangers into Funston’s prey. Both would be famous, both see themselves as liberators, and both be disparaged with racial slurs. The younger, David Fagen of Tampa, was a nineteen-year-old phosphate miner who worked hellish ten-hour shifts for one dollar a day. He wanted out, and saw that escape through the army. He’d travel the globe while proving to whites that the “Buffalo Soldiers” were anyone’s equal.

Another man, older by six years, argued with fellow patriots in a Hong Kong café. Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy, the Philippine Revolution’s unlikely embodiment, had evolved from an unknown provincial mayor to become the leader of eight million Filipinos. He was slim, stubborn, clever, and a little vain: even today, historians cannot agree on the man who became the Philippine George Washington. Nonetheless, in 1896-1897 his army fought Spain to a standstill, and he’d accepted exile in exchange for an end to the war. Now he wanted back, debating how to return. At the moment, all doors seemed closed to him. In an instant, Fate showed the way. Events of the next minute sucked American writers into its slipstream.

More famous and soon-to-be-famous writers would be crammed together in thought and proximity than in any other sixty-six-day span in U.S. history, and it changed the way Americans saw themselves. “There is precious little glory in war,” an unknown Frank Norris would write in six months: “I’ve made a roof for myself to sleep under, out of boards that were one glaze of dried blood, though I didn’t find it out till morning.” Within a year, he wrote McTeague, the ultimate condemnation of the American Dream. “I heard somebody dying near me. He was dying hard,” wrote Stephen Crane, already famous for The Red Badge of Courage. Where he’d plucked that novel from his imagination, the death rattle of a nearby army surgeon in a Cuban firefight would be all too attendant, James Pinckney, had just helped him don the coat; Sigsbee described Pinckney as “a light-hearted colored man, who spent much of his spare time in singing, playing the banjo, and dancing jigs.” Sigsbee realized that the man playing Taps was a marine bugler named Newton, “given to fanciful effects” when playing standard bugle calls. Both men were part of that comfortable onboard routine that barely brushed his consciousness. In another thirty minutes, both were dead.

At 9:40 PM Sigsbee hoped he’d apologized to his wife sufficiently. He sealed the envelope, and a huge explosion tore from amidships, followed by a sickening lurch. A “bursting, rending, and crashing sound or roar of immense volume” filled his ears. The Maine trembled and angled up, then listed to port, throwing him from his chair. The cabin’s eight electric lights snuffed out. Smoke and blackness enfolded him. Then he heard screams.

*

“Every war is ironic, because every war is worse than expected,” wrote the critic Paul Fussell—and even those who welcomed what spun from this moment’s cataclysm would stand aghast at the consequences. All three young nations snared by the conflict were more similar than any cared to admit, their volunteer forces born in waves of sentiment, each convinced it alone promised freedom—the second and most merciless of man’s ancient creeds.

All three believed themselves liberators—and made choices that echo today. Americans broke promises implicit in the way they imagined themselves. Cubans hoped to manipulate the northern giant, and learned otherwise. Filipinos were the most tragic, naïve in their choice of saviors, realizing too late that they’d exchanged one master for another.

What Cubans call the War of Necessity, Americans call the Spanish-American War. The difference suggests the fraught nature of memory. U.S. historians describe it variously as America’s first true war of empire, a commercial recasting of “manifest destiny,” a global assertion of machismo, or an adolescent yowp of “war fever.” The diplomat John M. Hay called it a “splendid little war,” proving once again that “winning” was a natural outcome of America’s virtues. The “manifest destiny” that swept away Native Americans to create a transcoastal nation fulfilled Heaven’s plan: “Away, away, with all these cobweb tissues of rights,” wrote the newspaperman John O’Sullivan, referring to the rights of Indian tribes. “The American claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us.” If Providence gave Americans the right to civilize a continent, why not the world?

The short war in Cuba gained the United States the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico; turned the nation into a Pacific power; and created beliefs that America was a stern yet benevolent country tasked by Destiny to enforce peace and bring prosperity to the world. If Cuba’s liberation created for Americans a vision of themselves as emancipators, the Philippine “liberation” turned so savage that the public shut it out of mind. It is easier to forget unsavory truths than to face them. The new Philippine Republic believed that the United States would deliver them from Spain, as it had the Cubans. Instead, the war that resulted transformed the archipelago into a post-apocalyptic wasteland of famine, disease, ecological disaster, and hundreds of thousands dead.

The Splendid War created this, becoming the template for every American “small war” in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It was a “war of choice” that started in a wave of idealism and disintegrated into brutality. America’s dependence on overwhelming force would form the assumption that, as in Cuba, war should be quick and relatively bloodless. Instead, outgunned opponents became an insurgency: the U.S. response throughout the coming decades would proceed with such near-identical ruthlessness as to seem scripted. Though usually treated as separate conflicts, the wars in Cuba and the Philippines should be seen as a continuum—one that begins with two similar Cuban and Filipino poet-martyrs who shape their nations’ identities and ends with the United States entering as a savior, only to become a scourge. One is reminded of the opening of T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, where the ideal of a people “devoted to freedom” heats first to an “unquestioning possession” and then to an “overmastering greed” for victory. “By our own act,” Lawrence wrote, “we were drained of morality, of volition, of responsibility, like dead leaves in the wind.” As we’d already done to Native Americans, in order to save them, we had to kill them.

Not until the conflict in Cuba and the Philippines did America’s love of war become so bold that one can track the transformation.

How did this happen so quickly, affect the individual American, and shape the national character? The consequences were as momentous as casualties were light: overnight it seemed the nation morphed into an imperialistic power in the mold of the European empires it disparaged. This was the war in which General Jacob Smith demanded, “I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn”; in which American doctors and a nurse martyred themselves against yellow fever; in which black Americans watched prejudice grow worse; in which an exhausted Clara Barton wrote, “Had the nation gone mad?” Others felt uneasy about a change they did not understand. On October 12, 1899, Minnesota governor John Lind tiptoed around his misgivings when welcoming home state volunteers from the Philippines: “The mission of the American volunteer soldier has come to an end. For the purposes of conquest he is unfit, since he carries a conscience as well as a gun.”

The United States was born in revolt; it survived the cataclysmic rebellion of 1861-1865. But not until the conflict in Cuba and the Philippines did America’s love of war become so bold that one can track the transformation. On June 2, 1897, Theodore Roosevelt told students of the Naval War College: “All the great masterful races have been fighting races, and the minute that a race loses the hard fighting virtues, then…no matter how skilled in commerce and finance, in science or art, it has lost its proud right to stand as the equal of the best. No triumph of peace is quite so great as the supreme triumphs of war.” The speech was published to glowing reviews and would be, in one form or another, justification for military buildup throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

With the events in Cuba and the Philippines, the United States increasingly became a “culture of war” with a sense of global purpose, prone to jingoistic eruptions. The rhetoric of war became that of patriotism: “God has not been preparing the English-speaking and Teutonic peoples for a thousand years for nothing but vain and idle self-contemplation and self-admiration,” claimed the Roosevelt ally Albert Beveridge. “No, he has made us the master organizers of the world” in order to govern “savages and senile peoples.” Even the Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper scribe William Allen White would rationalize the change: “It is the Anglo- Saxon’s manifest destiny to go forth in the world as a world conqueror. He will take possession of all the islands of the sea. He will exterminate the peoples he cannot subjugate. That is what fate holds for the chosen people. It is so written. Those who would protest will find their objections overruled. It is to be.”

The culture of war became indelible: a new Orwellian world in which, according to Paul Fussell, war becomes “peacekeeping” and the acceptance of any act “in the name of freedom” a citizen’s duty. “Those who challenged the authenticity of American altruism were by definition evil-doers and mischief makers,” observed the historian Archibald Cary Coolidge. “So fully were Americans in the thrall of the moral propriety of their own motives as to be unable to recognize the havoc their actions often wrought on lives of others.”

It’s easy for moral certitude and blindness to be one. At its heart lay a darker certainty: those who needed our help were lesser beings—because they were not American. It lay in the order of things that they accept American guidance; dissenters were not only misguided but corrupt, and thus enemies. The myth plays out often—in my life, from the Bay of Pigs to Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan. The leaders we elect always act surprised when things go awry.

Since one classical definition of mental illness is the tendency to repeat obviously self-destructive behavior, one wonders how deeply our cherished myths make us willfully blind and mad. Though those in power rarely heed historical lessons, neither do the Americans who vote them in. “A people unaware of its myths is likely to continue living by them,” warned the cultural historian Richard Slotkin, “though the world around that people may change.”

*

There are places where resentment shapes our image. Cuba and the Philippines rank high. Three nations forged modern identities in those years; each saw itself as freedom’s messenger. If the memory of the two wars is barely preserved in the United States, it lives in the collective consciousness of Cubans and Filipinos. In both nations, anger prevails for the injustices of those calling themselves saviors. The bitterness of the broken promise persists through centuries.

__________________________________

From Splendid Liberators: Heroism, Betrayal, Resistance, and the Birth of American Empire by Joe Jackson. Copyright © 2025. Available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, an imprint of Macmillan.