I conceived of my novel in a very different world. When I began writing my first draft, I was tutoring English in the region of Ukraine where my family came from. I went to Ukraine in search of clarity around my own diasporic relationship to the nation.

Article continues after advertisement

Although I never achieved that clarity, I found something much better. I tutored English at a one-room schoolhouse in Ukraine between a lake and a vegetable garden. The school’s enrollment fluctuated but never hit double digits. Friendships came easily through my broken family-heirloom Ukrainian and deepened when I became fluent. Each day, I thought: “I have to write about this place.”

The embryo of my novel was a lighthearted coming-of-age story following a boy around my students’ age. It was contemplative, more atmospheric than propulsive, and devoid of any kind of violence. There was already a war in Ukraine, but it was seven hundred kilometers to the east, distant both geographically and psychologically, and it seemed to be slowing to a halt.

When the pandemic struck, I wound up back in my childhood bedroom in Massachusetts. I quietly continued working on my first draft. I fantasized about returning to Ukraine and finishing my novel immersed in its setting.

The war gave me tunnel vision, and my novel was hidden in the dark periphery.

The world stirred back to life, and I moved to Denmark to finish my bachelor’s degree. Of all the exchange programs my university offered, Denmark was the closest to Ukraine; at the time, a plane ticket to Kyiv was comically cheap, if you were willing to fly certain off-brand airlines. I planned to bounce back and forth between the two nations with cosmopolitan, European ease.

My plan never came to fruition. One evening, a few weeks after I moved to Denmark, my student texted me, nervous about a competition the next day. We chatted for a little while, sent each other a handful of memes, and bade each other good night.

Nine hours later, he called me. The competition was cancelled and he was with his family in the basement. Russia had invaded.

I stopped writing for a year.

My hiatus wasn’t a conscious decision. The war gave me tunnel vision, and my novel was hidden in the dark periphery. I spent the year visiting my friends, my students and their families as they scattered across Europe. I handed out sachets of baby formula at a refugee camp. I briefly took up smoking.

I still held class for whichever students could show up. When they had electricity, they appeared one by one on my computer screen in shelters and basements. The content of our meetings was less academic and more therapeutic.

I spent a few weeks sleeping on my childhood best friend’s floor in Berlin, where I was volunteering at the Hauptbahnhof. One night, unable to fall asleep, I asked her: “What the hell am I supposed to do with all of this?”

The answer, of course, was to write. But, when I opened my first draft, I couldn’t bring myself to type; I just stared at it, reevaluating its existence. What I had already written was irrelevant, almost offensively so. And the very act of writing felt like a frivolous use of time.

Fiction can convey truths that journalism cannot.

The following February, I volunteered at a camp for Ukrainian kids in Romania, just over the border from Ukraine. Miraculously, all of my students were able to come. On the one-year anniversary of the invasion, we sat around with tea and biscuits, neglecting a game of Uno and exchanging stories of the last year of our lives.

“You guys should write a book,” I said.

“We’re busy,” one of my students answered. “You do it.”

My student’s blessing—or his command—galvanized me. I exhumed my first draft and reexamined it. I decided that it could be redeemed, but only if I took it in a completely different direction.

I decided to repurpose it and turn it into the foundation for an entirely new novel. I wanted to bring both peacetime Ukraine and wartime Ukraine into a single work. I had met multiple Americans who had never heard of Ukraine before the full-scale invasion. It infuriated me that the country I loved—and, in some ways, to which I belonged—was only associated with its neighbor’s campaign of destruction.

I spent six months finishing my second first draft. I spent as much time researching as I spent writing. I’m intimately familiar with peacetime Ukraine, but I only knew wartime Ukraine from afar, and I needed to render it with the depth and precision it demanded.

I conducted interviews. A few dear friends who survived war crimes shared their experiences in detail and allowed me to use them in my book, which was an act of unbelievable generosity. I interviewed an acquaintance who escaped Ukraine on foot; we sat for four hours with a contour map as he walked me through every step of his journey. Each of my interviewees offered a similar explanation for their willingness to speak: even if it was painful to relive these experiences, literature is a force for peace and solidarity. Fiction can convey truths that journalism cannot. The rest of the world needs to understand what has been lost, and what Ukrainians are still fighting for.

The context in which a novel is published is largely out of the author’s control. In my case, it took four years of sporadic writing, six months of disciplined writing, and three months of editing until my manuscript was presentable. Another year and a half elapsed before I held a physical copy.

The world will change as you write, and your novel may have to adapt. Or your novel may begin to morph of its own volition, and you will have no choice but to follow it. That’s why flexibility is so crucial and why you shouldn’t treat your original outline as gospel. You may find that the novel you finish is better than the novel you started.

__________________________________

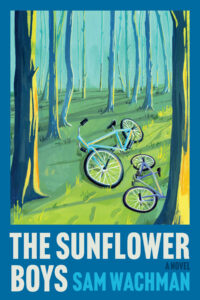

The Sunflower Boys by Sam Wachman is available from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.