The following review is for a book published in 1963 and this review, and the book, mentions some very questionable attitudes toward age differences, along with sexualization, paedophilia, and physical assault.

For a while there, I studied Anthropology at university. Why? I was curious. Reading this book felt like my own anthropological expedition, albeit 20-odd years after I studied the subject. I realise it is a sample of one, but it was a fascinating insight into the world of romance novels according to one woman in 1963.

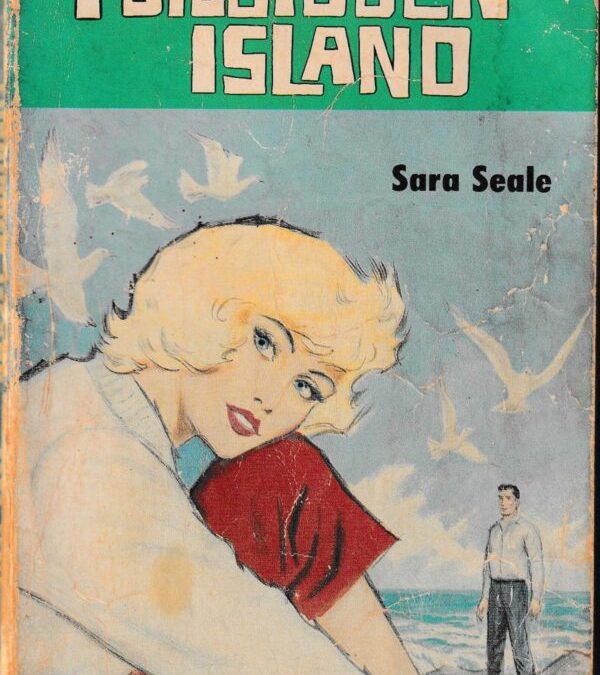

I present to you: Forbidden Island by Sara Seale

For the princely sum of two shillings and sixpence (British currency pre-decimalization), this book could have been yours 62 years ago. Converted to Pounds and Pence (by my father, relying on ancient memory alone) this is 25 pence. I have no concept of what it would be in today’s money. But this is a romance novel blog, not an economics one. Feel free to sound off in the comments with the answer!

I confess, I love this cover. The frank look of our heroine at the reader. The tiny man at the back. Nevermind that in the book our heroine has long hair and eyes the colour of peat smoke. And that our hero only wears kilts. Small details.

The blurb is a good one in that it gives you a good idea of what to expect.

And here we have our first dose of WTF. David (not the hero) is our heroine Lisa’s cousin, guardian AND soon-to-be fiance. In the book, this is treated as a totally normal thing. No big deal! IN FACT, the deceased Uncle Toby (the original guardian) wrote in his will that if David and Lisa marry anyone other than each other, they lose out on the inheritance from Toby. Matchmaking from the grave! And this is just in the first few pages!

Lisa finished school and then spent a year in Switzerland at finishing school. After that, she moves back to London and stays in a series of hotels or with David’s friends. David doesn’t have a set abode. He is urbane, a bit neglectful and far more interested in having affairs with other women. This is something that Lisa looks upon with benign disinterest. She’s not bothered by Mrs Gilroy and her like. David and Lisa are planning to become engaged. Lisa has always been a bit infatuated with David and it seemed only natural to fall in with his plans.

They take a trip to Scotland to see the sights. At one stage, David is called back to London ‘on business’ (the man does NOT work: he’s called back by Mrs Gilroy) so he leaves Lisa in Scotland and off he zoots.

While Lisa was still in finishing school, David would send her letters. In some of these letters, he wrote most passionately about a small Scottish island called Culoran. Tales of the island were abruptly cut off, but Lisa’s fancy was caught. So having been abandoned in Scotland, she decides to travel to the island by herself.

Only once she gets to the island, the laird there, Sir Charles Kiltyre, decides to take her hostage. It seems that while David was staying there he ‘dishonoured’ one of Charles’ subjects and now David must travel back and make reparations by marrying the girl. So feudal! So fucked up!

The blurb is not wrong: Lisa’s imprisonment is gentle for the most part. She stays in the castle with Charles and his grandmother. There are a handful of loyal servants. And then of course the people that live on the island. They are all loyal to Charles and would not help Lisa escape.

Despite this, Lisa spends fully half the book trying to escape. She even has an escape attempt just before the end, but at that stage she is running more from her feelings for Charles than anything else.

Lisa is 19 and Charles is 34. That by itself is pretty gross, but it is made infinitely more gross by the constant talk of how Lisa is not yet a woman and still a child.

There is a particularly memorable line uttered by Charles (brace for ick factor) when he first sees Lisa:

“… and looked curiously at Lisa, seeing not the woman he had expected, but a child uncomprehending of adult ways, with her slight, sexless body and her indecent lack of skirts.”

(She’s wearing trousers.)

When they finally confess their feelings to each other, Charles shares:

“You’ve always been a woman for me, Lisa – even when you kicked my shins,” he told her with great tenderness. “Don’t be sorry that you are a child too, for I think I’ll always love the child the best.”

Either this is a book for paedophiles or conceptions of childhood v womanhood were very different then to what they are now. It’s startling to read with today’s perspective.

That shin-kicking Charles mentioned?

Charles and Lisa climbed the mountain on Culoran together and when they were at the top, Lisa was irritated with Charles and so kicked his shins but nearly fell off the mountain in the process.

What was his response?

“You daft little wild cat, you can’t play tricks like that in the mountains!” he exclaimed and before she was aware of his intention, he had dropped on one knee, thrown her across the other, and spanked her twice, very hard.”

I mean, what does one even say.

He eventually apologises for it, but…. Wow.

I’m a big fan of historical romance, but reading old contemporaries is a different way of approaching it. There were countless references in the book that underscored the time period. My favourite was this mention of accessories when Lisa was disembarking from a train in summer:

“She was aware that her new hat had slipped to the back of her head and that she had lost one glove in the train.”

To match the feudal lord’s views on a woman’s ‘chastity’, this is how Lisa felt about Charles towards the end of the novel:

“If you loved a man, she thought, then it was good that he should be father as well as husband, good that beneath the woman the child should never be lost”

And then just to add a little salt, her views on colonisation. Charles is saying that he’s proud to be Scottish.

“Perhaps,” she said demurely, “all conquered countries feel like that – to bolster their defeated spirits.”

To focus on the romance plot for a bit, there are instances where both Lisa and Charles are separately in peril and the other worries for them greatly. This is the full extent of any romantic feelings until the last page of the book. There is a kiss as punishment. There is softening towards each other, but riddled with perpetual misunderstandings. There is none of the deepening emotional connection that is common in today’s romance novels. I’m curious if this book is representative of the time in that regard. If Lisa falls in love with anyone in this book, she falls in love with the island. She is captivated by its beauty and wildness. That is about the only part of the book that would qualify as a romance today.

This book was a fascinating if grim insight into what 60 years of feminism can do for a genre. It’s also given me insight into what feminism has done for me. When I first read this book, I was little older than Lisa. At the time, I felt swept away by the romance of it. I read and loved this book when I was in my early 20s. I look back on it now, startled that I ever felt that way. For context, at the time, Wuthering Heights was my favourite book, so I was deeply in need of a feminist intervention. Thank heavens for university.