“Basketball is like poetry in motion, cross the guy to the left, take him back to the right, he’s fallin’ back, then just J right in his face.” If you dig basketball, you might know this quote from the fictional Jesus Shuttlesworth in He Got Game.

Article continues after advertisement

Hell, it might even be a bit overplayed at this point. Even so, this line has followed me around for years. First, when I was playing, whether it was a Sunday pickup game or an NCAA tournament game, and my body took over, taking me and the ball places I didn’t know was possible: I was floating, I was twirling, I was showtime; I was unconscious. And that experience, that high, it was often the only thing keeping me alive. I could step on the court and forget the facts of myself for a while.

Now, I think of that line again when I watch the game being played how it’s meant to be played, when it’s beautiful and instinctual, unselfish and insightful, emotional and collaborative, when it’s five players on the court working as one, reading each other’s minds and bodies. That’s the shit I love.

Watch her play for even one minute, and it’s like encountering the most beautifully strange, unignorable first line of a poem.

And here’s the thing, not all basketball is poetry, let’s be clear on that. Some teams, some players just don’t have it going on, and that’s alright, they find their place outside the world of art. What I mean is, there are players, and then there are visionaries; Chelsea Gray, aka Point Gawd, #12 on the Las Vegas Aces, is a visionary, a seer, and to look away, for even a second, from the court where her handles deceive and her passes dazzle, is to risk missing out on magic, on the delight and holy surprise of witnessing a creative genius at work. Watch her play for even one minute, and it’s like encountering the most beautifully strange, unignorable first line of a poem and feeling destabilized, feeling delighted in that destabilization, knowing that if this is where brilliance lives, you never want to be stable again.

A prayer: There’s never been another player like her, and there never will be again.

Her poetry is everywhere, all the time. When I watch her, I feel like I’m witnessing something beyond me, something heavenly and incomprehensible, something beyond thought, and touch, and spirit. I feel the same way when I read “Meditations in an Emergency” by Cameron Awkward-Rich. Every time I read it, something in me rearranges itself to make room for more heartbreak, for more tenderness. Hand on my heart. Hand on my stupid heart.

Anne Carson said, “A poem is an action of the mind captured on a page. It is a movement of yourself through a thought, through an activity of thinking, so by the time you get to the end you’re different than you were at the beginning.”

I am changed after I watch Gray play; I am changing as I watch her play. I am made and unmade, repeatedly, for forty minutes. I am watching a poet work in real-time. It’s vulnerable and spectacular; it’s terrifying.

When she catches the ball at the three-point line and gives you a convincing pump fake that gets you in the air, how is that not like enjambment in a poem? When the reader thinks they’ve arrived at the end of the line, but no, the poem faked them out, it keeps going. There is more to the story.

And when she shakes you down and penetrates the paint, when you’re sure she’s going up with the right, but then she hits you with a spin move so quick you forget your name for a second—that’s a volta, baby, and it makes your head spin like the first time you read Thomas’ “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” and learned what the good night really was, how it wasn’t very good at all.

And when the shot clock starts winding down, and the Aces need a bucket, the ball is almost always in her hands, the hands of a playmaker. And when she stands at the top of the key, lulling you to sleep, when she crosses, right to left, then crosses again, left to right, before leaving you to nurse your bum ankles, that’s repetition, baby. The repetition of that double cross gives her game significance, and rhythm, and Gray, well, she’s dancing her ass off out there, she’s making it all look so easy, like she’s the only one who can hear the music, like she’s both maker and appreciator of the song, a wandering troubadour. And she’s got miles to go before she sleeps, she’s got miles to go before she sleeps.

Man, and when she’s feeling herself, when she’s making behind-the-back passes, behind-the-head passes, no-look passes that fake out everyone, even the ref—that’s free verse, no constrictions, no form, no prescribed meter or rhyme. She’s just out there doing her thing, and damn, does it look good on her. Not everybody can do it, I mean, not everybody can handle that kind of freedom, but Gray? She’s a stampede, and you better get out of the fucking way.

When she’s really showing out like that, when she’s got the announcers shouting “CHELSEA GRAY IS IN HER BAG,” she might, after a particularly jaw-to-floor play, one that disrupts our ideas of physics and possibility, hold an invisible video camera to her eye, evoking a highlight reel—and you better believe that’s an apostrophe, calling on the artistic geniuses of past, present, and future. O, playmakers! O, innovators! O, truth-tellers!

And when somebody scores on her, when she comes back down the court, eyes full of wicked heat, when she uses that same damn move against her defender—one you didn’t even know she had in her repertoire, one she maybe didn’t have until her fury made it possible—when she scores that bucket, that’s rhyme baby, the second line of a heroic couplet made possible through muscled bodies, will, and desire, the desire to reach another plane, to birth and destroy.

And when she’s on fire, when she knows good and well nobody can touch her, let alone stop her, when she comes down the court with a smile on her face and pulls up for a three from three feet beyond the arc, when she then pickpockets the ball handler on defense and throws a full-court no-look pass to a teammate for the easy lay-up, when she hits another three and then another, and when the announcer, intoxicated and awed, screams for the third time that game, “HOW DOES SHE DO IT?”—that’s a refrain, baby. The refrain that carries the team through the game, carries us through our experience of greatness, the refrain that we understand we will never quite get an answer to—the howness, the magicians-never-reveal-their-secrets of it all. The refrain that keeps us coming back for more.

When the Point Gawd does a little cross, cross, between the legs, cross, between the legs, step back jumper in your face, when you foul her on the shot and the bucket is good, it’s an and-one, and when she does a little shoulder shimmy on the floor, that celebratory dance is an ode to herself. And good for her. Part of being a genius, in my opinion, is knowing when you are and are not worthy of celebrating.

Your game is sublime, intoxicating and big-hearted, inducing a sort of rapture in me, a sort of non-loneliness.

I want to talk about Chelsea Gray’s 2022 season, how she showed up and showed out only to be snubbed when it came time for All-Star picks. She took that shit in stride, had a playoff performance fans will tell their grandkids about, led the Aces to a WNBA championship, and was ultimately named Finals MVP. She made sure everybody knew what a mistake they made—god, what could be more poetic than sweet, victorious revenge? That historic playoff run was a sonnet, an argument for her place among the greats, among the living gods. (Shall I compare thee to a planet blazing so bright nobody can look at it directly?)

And she got that place she so deserved. “I don’t think anyone on planet Earth can stop her,” said the Seattle Storm coach right before the Aces eliminated them.

A prayer: Have mercy on us, those of us who one day have to learn to let her go.

I don’t believe in god, but I believe in the Point Gawd, I believe in my living room as a house of worship, I believe that Martin Shaw was only half right when he said we “make things holy by the kind of attention we give them,” that he was neglecting, or perhaps unaware of, the innate holiness of Chelsea Gray, which isn’t dependent on who and who is not giving their attention over to her.

O, Point Gawd, if I can no longer play the game, if my torn and weathered knees no longer allow it, if playing means I am compromised, like an unruly ghost, like an echo that gradually quiets, it’s okay—really, I mean it—because your game is sublime, intoxicating and big-hearted, inducing a sort of rapture in me, a sort of non-loneliness, and well, truth be told, the hold I have on this life is tenuous, at best, and sometimes, having a tip-off marked on the calendar is enough for me to hang on, just a little while longer. I make it through entire seasons this way: one Chelsea Gray is in her bag at a time.

__________________________________

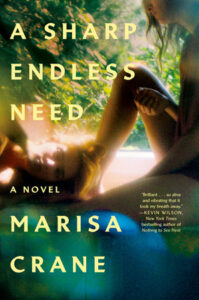

A Sharp Endless Need by Mac Crane is available from The Dial Press, an imprint of Random House Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Featured image: Lorie Shaull, used under CC BY-SA 4.0