This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Article continues after advertisement

As I think about embracing authenticity and imperfection—both in life and in art—the metaphor I keep coming back to is kintsugi, which translates to “golden joinery.” Kintsugi is the centuries-old Japanese art of mending broken ceramics with gold. You’ve probably seen examples, either up close or in photos: ceramic bowls repaired with gold; depending on where the breaks occurred, they almost look veined with it.

The artist doesn’t hide the cracks, but fills them with lacquer dusted with powdered gold, silver, or platinum, so that it gleams where it was pieced back together. The artist honors the object’s history—what it went through to become what it is now, including being broken. And the artist gives the object new life.

So what does it mean to honor the history of a piece of writing? If you’re like me, your poem or essay might go through anywhere from two to two hundred drafts before you’re satisfied enough with it to call it “done” and send it out. Each revision, ideally, gets us closer to the piece we sense is there, waiting. The piece that will do the psychic or spiritual work we want it to do. But each revision can also pull us farther away from the initial spark that drove us to the page. This tension, this push and pull, is what makes revision dynamic and exciting: we’re hunting something but aren’t quite clear about what it looks like or how to find it.

When I think about accepting the gift our poems give us in the guise of error, I think of the advice that we Midwesterners know all too well about driving in ice and snow: Steer into the skid, not out of it.

We can honor the object’s history by allowing the process to show. In this way, the break isn’t something that happened after the piece was finished—after the bowl was formed and fired and glazed. The breaking is part of the writing process, part of the story of the object being made. Maybe the piece of writing wasn’t finished, not fully itself, until the break.

We often say, “make it or break it.” I’m on the side of “make it and break it.” Or make it by letting it break and seeing what might come of it.

Perhaps kintsugi in writing is when the writer makes a mistake but decides to keep it, and in fact calls attention to it, leaning into the mistakes—mishearings, misreadings, misunderstandings, even typos—and filling the breaks with gold. The error—if we may call it an error—leads to new insights, layers of meaning, or exciting associative leaps that make the poem more of itself, not less than. The mistake, in fact, is a gift. The break, or breakdown, allows for a breakthrough.

“Written Deer” from Goldenrod is one example. I was reading poems by Wisława Szymborska when I came across this line: “Why does this written doe bound through these written woods?” The question made me want to push further into the setting—the written woods—and to consider what it means to both create and experience (or write and read) a place. I draft all of my poems longhand, often writing very quickly, and in my messy half-print, half-cursive handwriting, world and word were almost indistinguishable. As the poem came into focus, this conflation made its way into the poem’s argument. I could have left this error out of the poem, but it led me to consider what these two things have in common: “Either one could be erased.” That stark realization felt important to me, so it’s in the poem.

Written Deer

Why does this written doe bound through

these written woods?

—Wisława Szymborska

My handwriting is all over these woods.

No, my handwriting is these woods,

each tree a half-print, half-cursive scrawl,

each loop a limb. My house is somewhere

here, & I have scribbled myself inside it.

What is home but a book we write, then

read again & again, each time dog-earing

different pages. In the morning I wake

in time to pencil the sun high. How

fragile it is, the world—I almost wrote

the word but caught myself. Either one

could be erased. In these written woods,

branches smudge around me whenever

I take a deep breath. Still, written fawns

lie in the written sunlight that dapples

their backs. What is home but a passage

I’m writing & underlining every time I read it.

Sometimes miswriting or mistyping a word can lead to a new insight that wasn’t accessible before. What may seem like a mistake may in fact be the most important point in the poem, the place where the poet discovers new territory. Or the part where the poem introduces the poet to its subject.

“How Killer Blue Irises Spread” by Kelli Russell Agodon was inspired by a misheard health report on NPR. The story behind the poem is this: A poet, also the mother of a young girl at the time, was listening to NPR and misheard the title of an upcoming segment. She thought she heard the announcer say “How Killer Blue Irises Spread” and panicked, worrying because there were blue irises growing in their garden, where her daughter played. The NPR segment was actually “How Killer Flu Viruses Spread”—but Agodon leaned into the misunderstanding and tried to imagine all the ways that blue irises could be dangerous or actual killers, and we see these imaginative leaps in the poem. This sense of play—the pleasure the poet had writing this piece—would not have been possible without the error.

When I think about accepting the gift our poems give us in the guise of error, I think of the advice that we Midwesterners know all too well about driving in ice and snow: Steer into the skid, not out of it. To keep from losing control you have to turn in the direction you’re sliding, even though you desperately want to wrench yourself in the opposite direction. In this poem, Agodon steers into the skid.

A poem is not only a temporal experience but a human experience—and we are imperfect. By allowing imperfection into our poems—by letting some of the breaks and repairs show—we are also allowing our humanity into our poems, and allowing for a different kind of intimacy between the reader and writer. Dylan Thomas wrote, “The best craftsmanship always leaves holes and gaps in the works of the poem so that something that is not in the poem can creep, crawl, flash, or thunder in.”

I read poems and essays to witness someone else’s mind at work, and these moments of error or brokenness, these switchbacks, help me see that work. In a sense, the gold that “fixes” the breaks in our work is the very material it is made of: language. And in Thomas’s words, the breaks are openings.

Allowing ourselves to falter, to be disoriented, to find a new foothold—that strengthens us, too. And of course all of this applies to living as much as it does to writing. We’re going to make mistakes. Instead of trying to hide the breaks, or revise a piece to “correct” the error and make it impossible to detect, we have another option, as these poems show us.

I hope you’ll let some of the seams show in your next piece of writing. I hope you’ll let some of the history remain. Challenge yourself not to buff out every scratch and sand down every splinter. Accept the gifts that arrive packaged as missteps. Acknowledge the breaks and let them shine.

_______________________________________

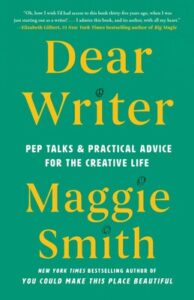

Excerpted from Dear Writer: Pep Talks & Practical Advice for the Creative Life by Maggie Smith. Available via Washington Square Press. All rights reserved.