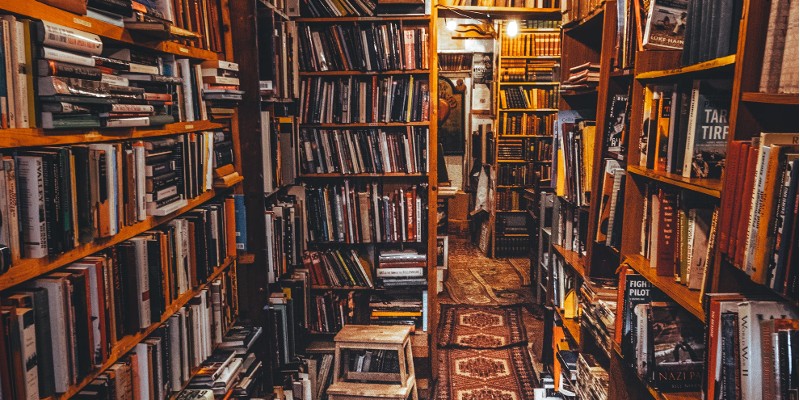

When I was growing up in the Philippines, our small resort town had none of the gleaming bookstores I’d later encounter as a graduate student in America, whose tall shelves containing crisp new releases made me feel inadequate and unlearned. The bookstores I knew were hole-in-the-wall shops tucked inside narrow alleyways of my hometown’s public market or the upper floors of old buildings, without so much as a street sign to advertise their presence. They sold paperbacks with creased covers and yellowing pages, and European novels, translated into English, with tiny, fuzzy print.

Article continues after advertisement

In sixth grade, I found a copy of Balzac’s Old Goriot in the upper shelves of my parents’ library, and was intrigued by its cover image of a walled garden shimmering beneath a wan, mournful light. I then sank into the story of Monsieur Goriot’s misfortunes at the hands of his overindulged daughters, completely forgetting all the chores my parents had asked me to do.

My father, unbothered, would happily water the plants I was supposed to water, preferring to spoil me over interrupting my enjoyment of Balzac. It was a book he hadn’t read: perhaps he had picked it up on his way home from the public market, slipping it inside his bag of produce before retiring it to our library’s upper shelf.

This was how my father had acquired his own literary education as a young man, his hunger for the written word sharpening his sense of what hid in bargain bins amongst piles of fashion magazines and dime-store novels. He had worked as a janitor to put himself through his first year of college, and while assigned to carry piles of books from one floor to another, he’d pause to read some of the books in the pile during moments of rest.

He borrowed, bought on the cheap, and swapped books with his closest friends. His language grew stately and formal from his reading of T.S. Eliot and W.B. Yeats.

The bookstores I knew were hole-in-the-wall shops tucked inside narrow alleyways of my hometown’s public market or the upper floors of old buildings, without so much as a street sign to advertise their presence.

Later, when we moved to the U.S. for a few years, he submitted his poetry to American literary journals. His work was always rejected, and it wounded him: “What matters to them is language, not substance,” he’d say, after receiving yet another rejection note. “I didn’t grow up speaking the English they speak, that’s why they won’t listen to me.”

But the U.S. also had its way of shaping his tastes, of creating a fondness for the largesse of ideas and creativity that came with its power and wealth. While living in the U.S., my father became a fan of The New Yorker, and when we returned to the Philippines he discovered, right beside a dried fish and tobacco shop inside the public market, an open-air stall that sold decades-old New Yorker magazines.

He would bring home an issue from the seventies, pointing out a poem he liked by an author whose name was as unfamiliar to him as it was to me. Never mind if I was just eleven years old; I was already writing my own poetry by this time. It was almost as though he thought of me as a confidante with whom he could share the poems and stories he loved.

He refused to underestimate me, and neither did he underestimate himself: we were citizens of the world, partaking of its ideas and creations, never mind if our magazines and books were all hand-me-downs, cast aside by first-world readers who had access to all the reading material they wanted and more.

One of my father’s favorite second-hand bookstores was on the second floor of an old art deco building. Inside was a bespectacled old woman who later taught me how to knit, who listened to the news on an old transistor radio while my father and I browsed musty shelves crammed with old Algebra textbooks and celebrity memoirs.

I remember the piles of fashion magazines from the eighties and nineties spiraling upwards from the wooden floor near the shop’s window, Cindy Crawford or Linda Evangelista throwing their come-hither looks at the morning light filtering through the window’s fine layer of dust. My father’s fingers had their way of digging up treasures inside this cramped little store: an issue of National Geographic detailing child sacrifices of the Incas, Isak Dinesen’s Seven Gothic Tales, an Algebra textbook that helped me survive freshman high school math, a lesser-known novel by Virginia Woolf.

His favorite anthology of English verse lacked a cover, and when he placed it in my hands after reading my first attempts at poetry, I had to turn the pages with care, lest an entire section fall out. If I was struggling with a poem, he’d guide me through each line, bringing my attention to each turn of phrase, each word choice and placement, each rise and fall of breath as he read a poem aloud.

I became attuned to language the way a student of sailing grows attuned to the water’s chop, to the wind’s particular inclination and mood. English was my father’s second language, and it was also the language in which he was first introduced to the written word. It was a language that spoke to us and inhabited our thoughts as it became a vessel for our ideas, our flights of fancy, our deepest yearnings.

Our reading list was predominantly white and English-speaking, with some Europeans, Indians, Latin Americans, Chinese, and Japanese thrown into the mix. The Russians loomed large in our imaginations, impressing us with their eagerness to ask the big questions, to convey the entire tragedy of a person’s life within a single gesture or line of dialogue.

The disappointments of Turgenev’s, Chekhov’s, Dostoyevsky’s, and Tolstoy’s characters reminded me of the quiet disappointments of the people in my life, and it felt strange to think that the people I knew could also be characters in these yellowing pages, that their heartbreaks and joys were equally worth sharing with the world.

And yet it seemed liked nobody cared about the stories of people from our little corner of the world, judging by the books that made it into our second-hand bookstores from the libraries of American and Australian readers.

It wasn’t until college that I made a deliberate effort to read books by Filipino authors, feeling guilty about my Westernized tastes and my neglect of a literature that sometimes failed to speak to me. Writers like Kerima Polotan, F. Sionil Jose, Nick Joaquin, Antonio Enriquez, Edith L. Tiempo, and Cirilo Bautista wrote in English, while also expressing a sensibility I wouldn’t necessarily call American or British.

These were writers who, like my own father, had acquired their literary education from English-language books assigned to them in school or discovered in second-hand bookstores. English enabled these writers to engage with a larger international exchange of ideas—an exchange which would otherwise dismiss their very existence.

But they didn’t just use the colonizer’s tongue passively. Wilfrido Nolledo, Erwin Castillo, and Cesar Ruiz Aquino pushed the limits of the English Language with their experiments in grammar, semantics, and point of view to embody the uniquely hothouse atmosphere from which their perceptions and sensitivities arose. The more I read their work, the more I gained confidence in my own worldview, which was informed both by my very Filipino experiences and by the language in which I had learned to convey these experiences, which happened to be English.

It was during the first year of my MFA program in the US that I felt the limits of my third world literary education closing in on me. My classmates would casually mention Denis Johnson and Jennifer Egan over drinks, while I’d nod and quietly pretend to know who these people were.

The books I’d read in the Philippines no longer mattered in this space: they were the writers of yesteryear, their stories and poems buried within the shifting literary landscape. The copies of Ploughshares, Missouri Review, and Best American Nonrequired Reading I’d gotten ahold of at pop-up bookshops in the Philippines were five, sometimes fifteen years old, and the authors I’d discovered through these journals and anthologies were now mere afterthoughts, if at all, in the heated conversations of my peers.

I was anxious to impress them, and ashamed of the dated influences that had made their way into my work, the way a poor kid is ashamed of the scuffed shoes they have to wear on their first day of school. Hand-me-downs had helped gain me entry into an elite creative writing program in America, and I felt like a poor scholarship kid playing catch-up with classmates who knew they belonged in this space.

It took me a few more years to take pride in the voice I had honed through the books and magazines my father and I had found in bargain bins and open-air stalls. By this time, I no longer cared about chasing the latest trends and coolest names in literature, instead settling for the books that spoke to me, whatever year they’d been published.

It took me a few more years to take pride in the voice I had honed through the books and magazines my father and I had found in bargain bins and open-air stalls.

Outside the academy, I was learning to trust my gut, to be guided, like my father, by sheer instinct while sifting through the mountains of reading material produced every year and during past years. For how was I to hone my voice if I were to follow every passing fad, knowing that my tastes and obsessions remained constant, gifting me with my own true north?

When I returned home shortly after my father’s sudden passing, I rediscovered my father’s books in my childhood home, dogeared and lovingly chosen from the crammed shelves of bookstores that had long shuttered. He was no longer around when I cracked open The Magic Mountain, a novel he’d read twice in different translations and frequently commented on, but when I discovered his squiggly handwriting fighting for space in the margins of Settembrini’s and Naphta’s arguments, I felt his voice gently guiding me towards the values he held dear.

We are part of this conversation, he seemed to be telling me, reaching across the vast distances of time and space to pull me deep into this book. Tell me, aren’t they both charming?

______________________________

Returning to My Father’s Kitchen by Monica Macansantos is available via Curbstone Press.