Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, SC on June 2, 2025.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

CHARLESTON, South Carolina — June 17 marks 10 years since a deadly mass shooting at Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church shocked the nation. A white supremacist, intent on starting a race war, opened fire during Wednesday night Bible study, killing nine Black worshippers as they bowed their heads in prayer.

“I was here the night when it happened, but I left before he came in and did the damage,” says longtime church member Theodora Watson.

“I still don’t forgive him because you took something out of us and out of this church,” she says of the shooter Dylann Roof, now on federal death row for the murders.

Church member Theodora Watson at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church on June 2, 2025.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Twice a day, the church bells toll nine times, one for each of the Black worshippers killed, now memorialized as the Emanuel 9. They are the Rev. Clementa Pinckney, Cynthia Graham Hurd, Susie Jackson, Ethel Lee Lance, Depayne Middleton-Doctor, Tywanza Sanders, Daniel Simmons, Sharonda Coleman-Singleton and Myra Thompson. Five others survived — Polly Sheppard, Tywanza’s mother Felicia Sanders and her granddaughter, and the pastor’s wife, Jennifer Pinckney and one of their daughters.

“The church was violated,” says Melvin Graham, brother of Cynthia Hurd. “The family was violated, the community was violated.”

Even a decade later, the memories are fresh for the parishioners here, and it’s hard for them to welcome strangers as their faith demands.

Melvin Graham, Jr., brother of Cynthia Graham Hurd, one of the nine Black worshippers killed at Emanuel AME. He wears a charm with Cynthia’s image on his necklace. “When she was executed, I made a promise to be her voice,” he says.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

“I try to help people understand that we as the church still experience trauma,” says the current pastor, the Rev. Eric Manning. “Every day I come into what was a crime scene. The space where people lost their lives.”

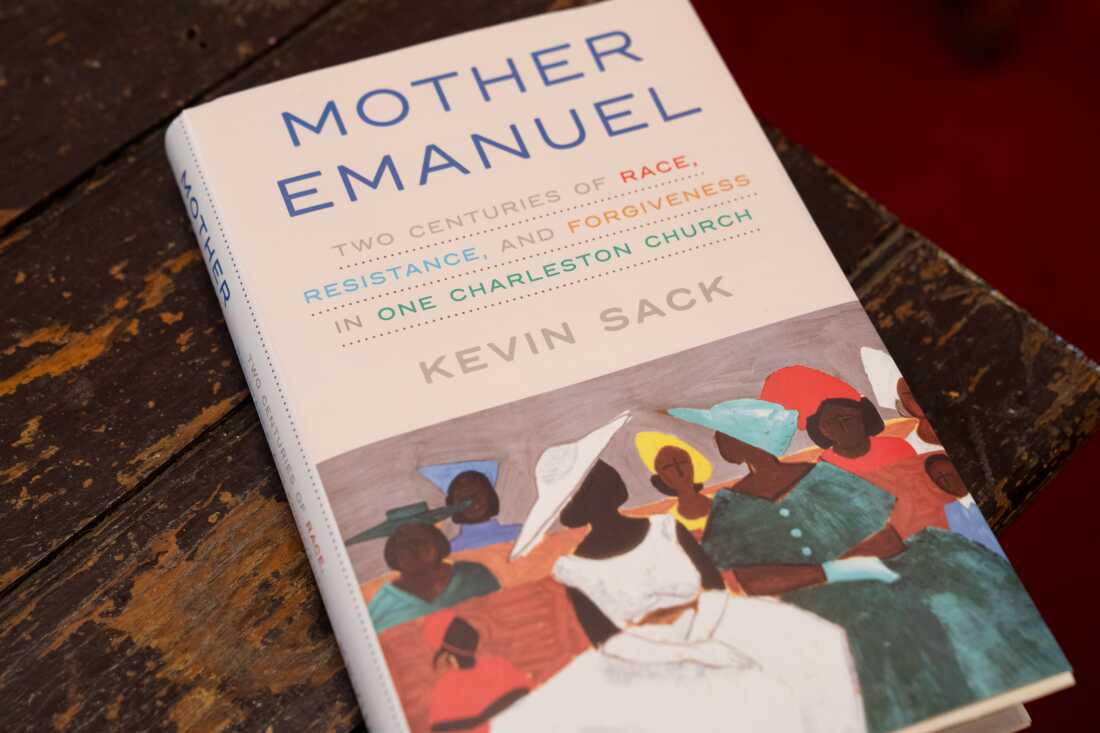

Reporter Kevin Sack’s new book frames the tragedy by looking at the historical legacy of the oldest Black congregation in the South, known affectionately as “Mother Emanuel” for its role is establishing the AME faith.

“As I was covering the aftermath for The New York Times, I just got fascinated by the incredibly rich history of this place,” Sack told NPR.

Titled Mother Emanuel: Two Centuries of Race, Resistance, and Forgiveness in One Charleston Church, Sack’s new book tells the story of how Mother Emanuel has been at the forefront of the struggle for racial justice since it was founded in an “act of bold subversion” by enslaved and free African-Americans in the 1800s.

The Rev. Manning says healing can only come if the congregation leans into that tradition.

The Rev. Eric Manning says Mother Emanuel’s legacy is to be “a light in the pathway of darkness.”

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

“We need to be intentional to make sure that we are carrying a message of hope, of resilience and of restoration,” Manning says.

Those themes — hope, resilience, and restoration — are woven throughout Kevin Sack’s biography of Mother Emanuel AME, as he told NPR’s Debbie Elliott during a recent interview from the polished pews of the historic sanctuary.

Author Kevin Sack (R) is interviewed at a book release event at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, SC on June 2, 2025.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

The following exchange has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Interview Highlights

Debbie Elliott: This is not just the story of that tragic moment and that heinous crime. How would you describe what you were trying to do with this book?

Kevin Sack: I was deeply affected by what happened here that night. It started to occur to me that there was a way to use the church as a vehicle to tell a much broader, larger story of African-American life in Charleston over a two century period. The property on which this building was constructed dates back to about 1865. But there was a predecessor congregation, only known as the African Church, that dates all the way back to 1818. And it was created during enslavement in an act of bold subversion. Free and enslaved Black Methodists withdrew from white controlled Methodist churches in this city and decided to create an autonomous congregation that we can control ourselves and where we can worship in the way that we wish.

Elliott: So it had symbolism that Dylann Roof chose this church?

Reporter Kevin Sack says he was moved to write “Mother Emanuel: Two Centuries of Race, Resistance, and Forgiveness in One Charleston Church,” after covering the aftermath of the deadly racist attack on the church ten years ago.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Sack: I don’t know that he knew it, but it had incredible symbolism. It’s the oldest African Methodist Episcopal Church in the South, one of the oldest Black congregations of any kind in the South. The church had a significant role in sort of every major era or movement that we document as part of the Black liberation struggle in this country, starting with the resistance to slavery. There was a slave revolt that was plotted in Charleston, known as the Denmark Vesey Conspiracy. The people who have spoken from this pulpit are remarkable. Booker T Washington spoke here in 1909. W.E.B. Dubois spoke from this pulpit in 1921. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1962. His widow came back in 1969, the year after his assassination, to lead a hospital workers strike. Throughout its history, the church has been a bulwark of protest against oppression and discrimination.

Elliott: This church has produced a lot of politicians over the decades, including the pastor who was killed on June 17th.

Sack: That’s right. Clementa Pinckney, who was the pastor at the time of the shootings, was an incredible prodigy. He was the youngest African American ever elected to the state legislature. He was serving his fourth term in the state Senate. At the time of the shootings, he was considered to be a guy with limitless possibilities for the future. The tragedy of his life being cut so short follows this pattern that we see right in the Civil Rights Movement of dynamic young leaders being cut down way before their time.

Kevin Sack’s new book is “Mother Emanuel: Two Centuries of Race, Resistance, and Forgiveness in One Charleston Church.”

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Elliott: You write that, “for a moment, June 17th seemed to be the night old Dixie died.” How has the idea of Charleston as a kind of model for reconciliation evolved over these last 10 years?

Sack: A couple of important symbolic achievements came in the aftermath of this event. The Confederate flag that was flying outside the statehouse in Columbia was brought down because of the close association between the shooter and the flag. There also was a resolution by the city council here to apologize for the city’s role in slavery. Interestingly, though, the vote on that resolution was seven to five. I do think there was a Charleston before 2015 and the Charleston after 2015, and they’re not exactly the same place. But it continues to be a city that is working its way through a very long and very oppressive racial history.