Oh, to have been born in a small, stylish country with good food and favourable sea breezes. No empire, no holy faith, no condescension, no fatal ideologies. The fish is grilled, the extended family roll in on their scooters, the wine looks amber in its glass as the socially democratic sun begins its plunge into the sparkling waters below.

This was not my fortune. I was born to one dying superpower and am now living in another. I was born to an ideology pasted all over enormous granite buildings in enormous Slavic letters and now live in one where the same happens in bold caps on what was once Twitter and what purports to be Truth (Pravda?) Social. America, Russia. Russia, America. Together they were kind enough to give me the material from which I made a decent living as a writer, but they took away any sense of normality, any faith that societies can provide lives without bold-faced slogans, bald-faced lies, leaders with steely set jaws, and crusades against phantom menaces, whether Venezuelan or Ukrainian.

I have written dystopian fiction before, and my latest novel, Vera, or Faith, is a continuation of the natural outcome of my birth in Leningrad and my removal, at age seven, to Reagan’s America. I think I have predicted the future with fairly good aim in novels such as Super Sad True Love Story, where social media helps to give rise to a fascist America, although my timeline when that book was published in 2010 was 30 years into the future, not a decade and change.

But before I wrote that book, there was a period of some optimism where, I confess, I got things terribly wrong. I imagined, in my least cynical moments, that Russia would become more like America over the years, or at the least more habituated to pluralism and the rule of law. Of course, the very opposite happened. America is becoming Russia with every day. The tractors I would watch on Soviet television leading to ever more heroic harvests are now tariffs that will bring manufacturing back to our land. The dissidents who were the Soviet enemy within are now the vastly fictionalised Tren de Aragua gang members who supposedly terrorise our land, and indeed all migrants deemed insufficiently Afrikaner. Politicians in all countries lie, but the Russian and American floods of lies are not just harbingers of a malevolent ideology, they are the ideology.

Vera, the titular character of my new novel, is a 10-year-old girl growing up in an America that is just slightly different from our own. Her best friend is an artificially intelligent chessboard named Kaspie (after the chess player), the car that drives her to school is an ingratiating AI named Stella, and the lessons of her school are preparing her for a constitutional convention that will allow certain “exceptional” Americans, ie those who can trace their heritage to the colonial era but were not brought to the country in chains, five-thirds of a vote. This is being done, Vera is continually told, not to diminish her rights (she, being half-Korean, would not qualify for the enhanced vote), but to honour the Americans who are exceptional by nature of their birth.

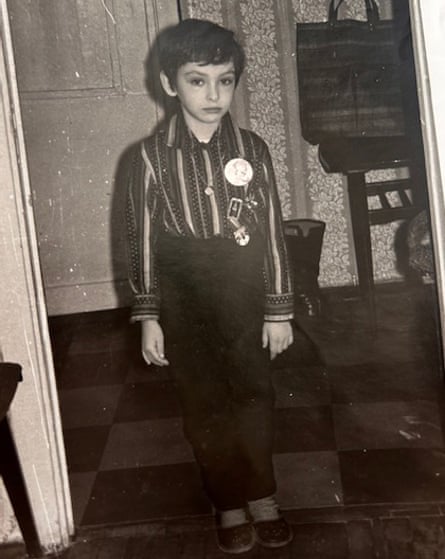

One reason I wanted to write from the point of view of a 10-year-old character – who, as it happens, is also half-Russian by heritage – is because of the way living in an authoritarian regime changed my own life. There was daily cruelty in the courtyards, classrooms and workplaces of the Soviet Union (not to mention the daily fisticuffs over nonexistent products in the food stores), but there was something else you could never forget even as a child: ubiquity. I grew up a stone’s throw from the biggest statue of Lenin in Leningrad; Lenin looked down at me from the walls of the kindergarten classroom in which my mother taught music; and the very city in which I lived had been renamed after him.

When I wrote Vera, my own son was 10, and Trump was every bit as much a part of his life as Lenin was of mine, from talk in the playground to conversations at the dinner table to the discussions of his social studies class. It is unsurprising that Trump’s sometime ideological consigliere Steve Bannon has chosen Leninism as a model for his hero’s rule. All mode of social inquiry, even at a fifth-grade level, must lead back to the scowling man on the television and telephone screen. My parents and I may have different styles of childrearing and certainly different politics, but despite our disagreements I will always honour them for getting me out of the Soviet Union at the right time. The question for my son as well as the fictional Vera remains: is it time to do the same with our children? Or is there still room to stay and fight?

Of course, there are large, some would say crucial differences between the Soviet Union of the 1970s and the Trumpistan that America has become today. Much as the comparisons of the contemporary United States with Hitler’s Germany are incomplete (though getting more complete by the day), Russia and America are hardly twins either. And yet, their increasing similarities raise the question of how the similarities that seemed nonexistent at the end of the cold war are becoming unavoidable now.

To start with, these are vast lands that stretch from sea to sea. Their size alone is enough to fuel messianic complexes, manifest destinies, divine rights. And religion, which can easily morph into ideology and then violence, drives the stupidity of both nations. In both societies, religion helped normalise the bondage of other human beings: slavery in America and the institution of serfdom in Russia. Inequality is baked into the national psyche of both, despite Russia’s experiments with state socialism: the idea that human beings must be parsed into a multitude of categories. Obviously, other countries have caste systems, but none has the capacity to impose its worldview on the rest of the globe with such stubborn resilience. The Soviet Union loudly professed the brotherhood of nations, but Russian racism remained thick and outlandish on the ground (ask almost any African exchange student), and was converted with great ease into a hatred of Ukrainians, with Russian television using animated images of Ukrainians rolling in the mud with pigs and references to a racial slur that can be compared with the worst used in the States.

Trumpistan dives right into this morass with the falsehood that some commonplace tattoos found on Venezuelan bodies supposedly signify gang orientation, but really emphasising that some people – brown or black or non-Christian or non-straight – can never fully claim the mantle of Americanness. There are, indeed, “exceptional” Americans, those that look like Trump and much of his coterie, and then there are those who semi-belong, or who may stay as long as they are useful, and then there are those who don’t belong at all and can be deported at will.

Trump loves Putin with good reason. Putin takes the messianic ideals that are found at the nub of both American and Russian societies and he makes something out of them that Trump can only find beautiful and instrumental to his own power and corrupt dealings.

As both countries enter headlong into postindustrial, likely artificially intelligent ages, Putin subverts the meaninglessness of Russian working-class lives with loud (though sometimes nonsensical and contradictory) narratives, rooted in a perceived insult to the messianic ideals of the fatherland. When, during his debate with the doomed Kamala Harris, Trump said that Haitian immigrants – those who would never be true Americans even if granted citizenship – are “eating the cats … eating the dogs”, he almost surpassed his master in terms of the clarity and shamelessness of his message, as well as an understanding of the audience for whom these comments were intended. It is most interesting to see older Russian-speaking immigrants in America, who fled the authoritarian USSR of their younger days, embrace Trump precisely because of the clarity of his message, their inability to deny a great leader shouting slogans that, if you take away their ideological direction, look much like the ones that lined the walls of our metro stations or the front pages of the newspapers we sometimes used as toilet paper.

after newsletter promotion

When I wrote Vera, there was one thing I couldn’t quite do to my 10-year-old heroine, which is to subject her to the threat of violence. She was simply too young for that, and also, because her family was financially privileged, less likely to face such a threat. But as I write this, in June 2025, Trump is taking the final steps of authoritarian progression in his attempt to label any protest against the unconstitutional nature of his rule as an insurrection that must be put down with military force. These attempts, as we can see, can be easily accepted by his followers, many of whom drink from the well of (often Russian-born) misinformation. There are parts of our population who are aching to shoot a brown “un-American” person at the border, in the same way many Russians without a purpose in life dream of profitably shooting a Ukrainian.

And whereas Putin has relied on his own praetorian guard, the Rosgvardia (or Russian National Guard), so Trump is stumbling toward his own force in the fiercely racist and loyal Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or Ice, which, in cities like Los Angeles and elsewhere, happily spreads the fuel with which our democracy may soon burn.

I want to take a step back and return to the mythical country with which I began. My favourite country in the world, Italy, is ruled by a political party with ties to Mussolini. Other countries I love are not paragons of social democracy and have little love of the “outsider”, although they may rely on exactly such people to care for their parents or raise their children. But the danger of America and Russia lies in the ferocity with which we believe, a ferocity that in Russia is fuelled by a justifiable anger (and built-in fatalism), given how the population has been ruled throughout the entirety of Russian history, and in America is enhanced by a population that, despite its relative wealth, reads below a sixth-grade level and is easily susceptible to manipulation. Ignorance, to add a pinch of Orwell to the proceedings, is the strength of both regimes. Convincing these populations that slavery was but a feeble blip on the radar of American history or that Ukrainians are porcine savages who precipitated Russia’s invasion requires a groundwork set by centuries of hatred and exploitation.

So where should my Vera live? It is hard to say, because living under these regimes is already preparing our children for the two choices they will inevitably face – to fight or to conform. And is it right to ask a child to give up her birthright, the right to live in a country that invented the grace of the blues, the easy slide of denim jeans, the sweet, almost religious voices of Walt Whitman and James Baldwin? That is a lot to ask of a 10-year-old.

The beauty of writing about a child is that you can see the monstrosity of the world adults have built filter through their innocence. But no child stays innocent for ever.