Author’s Note: Some names in this essay have been changed to maintain privacy.

In 1973, when my Uncle Ricky was nineteen, he robbed an ice cream shop in Tennessee. Too much Butch Cassidy and Bonnie and Clyde rags-to-riches stories. The silver screen had promised a kind of outlaw glamour, false hope for something better. But real life wasn’t like that at all. Broke as shit, and feeling as though he had nothing worth losing, Ricky waved his gun at two girls behind the counter, demanding they empty the cash register into his bag. He left without firing the gun and the money he walked away with was declared petty, but still, it was armed robbery. Ricky was sentenced to 52 years in prison.

Sometimes, when I can stomach it, I try to imagine what it must have felt like for him to receive news that in one fell swoop, his free life was already over. Without a fully developed frontal lobe, he was told he wouldn’t step foot in another arcade, or even a grocery store until he was 71 years old unless he was granted parole. Still, when I envision that moment, it makes perfect sense to me that Ricky made his first escape two years into that original sentence.

I first got involved advocating for my Uncle Ricky’s case in January 2023, fifty years later but nowhere near his release. It was an untethered winter for me. I was headed to New Haven, Connecticut for the spring semester where my girlfriend, Daisy, was set to complete a three-month research fellowship at Yale.

I was spending the week before our departure with my family in Colorado. Sleeping beside my mom in her bed and doing facial peels with my fourteen-year-old nephew. I spoke to my Uncle Ricky on the phone when he called my mom during their weekly Wednesday time slot.

My mom and Uncle Ricky are two of seven siblings—each with their own call day. Their white Southern family grew up exceptionally poor in Knoxville, Tennessee, where Ricky had told me stories about collecting pieces of coal by the train tracks to warm their house. Other times, all seven kids would crawl into their mom’s bed and pull the covers over their heads to share their body heat. While my granny always worked—at a grocery store or local shops—it was hard being the primary caregiver. My grandfather had done a stint in jail, and not long after his release, he stood up from the dining room table, declared he was sick of starving, and left the family. Seven kids being supported by one measly income had left the family in a kind of poverty that made you feel like you were born into a dead end, where the only options out looked like joining the military or trying to get rich with guns or drugs. All the sisters accepted their fate, worked low-paying jobs, had children, kept the cycle going, but Ricky went down the bandit route. Sure, he knew it could get him into a lot of trouble, but life was tough enough just getting by that it was hard to care about the risks.

An inmate from a Tennessee penitentiary is calling, an operator said. Then I heard my uncle’s pre-recorded, deeply Southern, “This is Rick.” I hit accept and the operator warned that the collect call was ten minutes long. It would be recorded and then terminated automatically.

“Well, hey there Shellers,” he said.

I asked him for any updates. There was no time to waste.

“Still haven’t heard nothing back from the parole board,” Ricky said. “But I’m hopeful. I’ve heard about some guys getting out because the prison needs more beds for incoming men.”

Ricky’s first escape from Tennessee sounds just as surreal as his robbery: he caused a distraction during an inmate softball game, throwing his bat in the air and running like hell to Alabama in 1975. By then he was 21. In the following 30 days, he robbed three convenience stores trying to survive life on the run, then was arrested again. Ricky spent four-and-a-half years in an Alabama prison before he escaped during a 1980 farm detail—sneaking off and fleeing to Virginia, where my grandmother and five of his siblings had relocated.

It’s been said that my grandma always left the back door unlocked for Ricky, just in case her baby boy came home. Unbelievable almost, that one day he actually did. It still moves me to picture my grandma getting her wish. I don’t know all the details, but as a kid, I liked to picture her waking up to find Ricky, standing in the kitchen, flipping pancakes, free as a bird.

In those years he was out, Ricky was determined to stay straight and get his life together. He worked under a fake name at Norfolk shipyards for two years, fell in love, and had my cousin in 1981. Then the shipyards started fingerprinting and Ricky had to quit. With a family to feed, and a fear that he couldn’t hide for long, my uncle did what a lot of us would have done—he went back to his old survival tricks. He’d been caught and arrested every time in the past, so what else, other than desperation, could have motivated him? Ricky completed a string of robberies and was arrested for good in 1982.

When I was a little girl, my mother explained that my Uncle Ricky was in prison for the rest of his life because of a “three-strike-law,” which was not the same as receiving a life-sentence. As a child, I understood this as a warning not to get into any trouble, especially not more than once, because the consequences would be severe. I didn’t think much of it beyond law-being-law, until I was an adult and started to learn about the prison industrial complex and how punitive our country is towards disenfranchised people.

This law stated that “any person convicted of three separate felony offenses of murder, rape, or armed robbery…shall not be eligible for parole.” Many prisoners, just like my uncle, were given parole dates during their official convictions—Ricky’s had been set for 1994, twelve years into his sentence—only to eventually be notified that this newly instituted law had been retroactively applied to their cases by the Department of Corrections, not the court or judge. These men were now going to spend the rest of their lives in prison.

Then, in 2018, something unexpected happened.

After serving 38 years, Ricky received notice that he had been illegally denied parole for the last 26 of them. The “three-strikes-law” was found to be defunct and unconstitutional, a gross overstep of the Department of Corrections. My Uncle Ricky was one of 260 men who would be freed in Virginia at its overruling.

A blessing, as my uncle, who was then 68, had undergone two heart bypass surgeries and survived colon cancer, had been given only a few years left to live by an oncologist.

Ricky completed all the necessary steps to reenter society. Fulfilled rehabilitation classes, filed paperwork to approve of his future residency, and applied for parole in Tennessee, where that original ice cream shop sentence still awaited him. It seemed reasonable enough that the state might consider his time in Virginia a concurrent sentence, especially considering that 26 of those years had been illegally overserved, an injustice that had also prevented his being extradited to Tennessee way back in 1994 to finish out his sentence.

Our family hoped that Ricky would live out his final years in my aunt’s spare bedroom in Heathsville, Virginia—helping her with chores, repairs around the house, gardening, eating home-cooked chicken and dumplings (my grandma’s recipe) and learning the ways technology has changed since 1982. Instead, he was extradited to a special-needs facility in Nashville, to serve a sentence he cannot outlive.

On the phone, Ricky told me it had been three years and he was still waiting to hear back from the Tennessee parole board. I pictured my uncle in his baby blue prison uniform, the surgery scars from two heart bypass surgeries under his T-shirt, and the after-effects of colon cancer leaving him unable to live in a standard federal prison. Easy to imagine the hope he’d felt given his freedom in Virginia, and just as easy to imagine the anxiety of being denied parole, or dying before his paperwork was ever looked at.

You have one-minute remaining on the call, the operator said.

“I have a lawyer friend,” I told him. I rushed it all out: A girl named Lily. She practiced law in New York, but I could still contact her. I’d tell her the situation. She might be able to help. Give some advice.

“Oh, Michelle,” he said. His voice was like a prayer. “I would be so grateful to you. Just for anything. Even just to know what she thinks.”

I didn’t understand yet how much faith this small gesture of getting in touch with Lily would restore. It’s nearly impossible to get legal guidance or support when you’re a flat broke, regular joe, when your whole extended family lives paycheck to paycheck. It had just been my Uncle Ricky and some of his prison pals writing letters and filling out the applications and his limited research ever since this Virginia misstep was brought to light.

We needed help.

“I’ll write and tell you what she says,” I told him, then we were disconnected.

This was his life now. He would be in prison until the day he died.

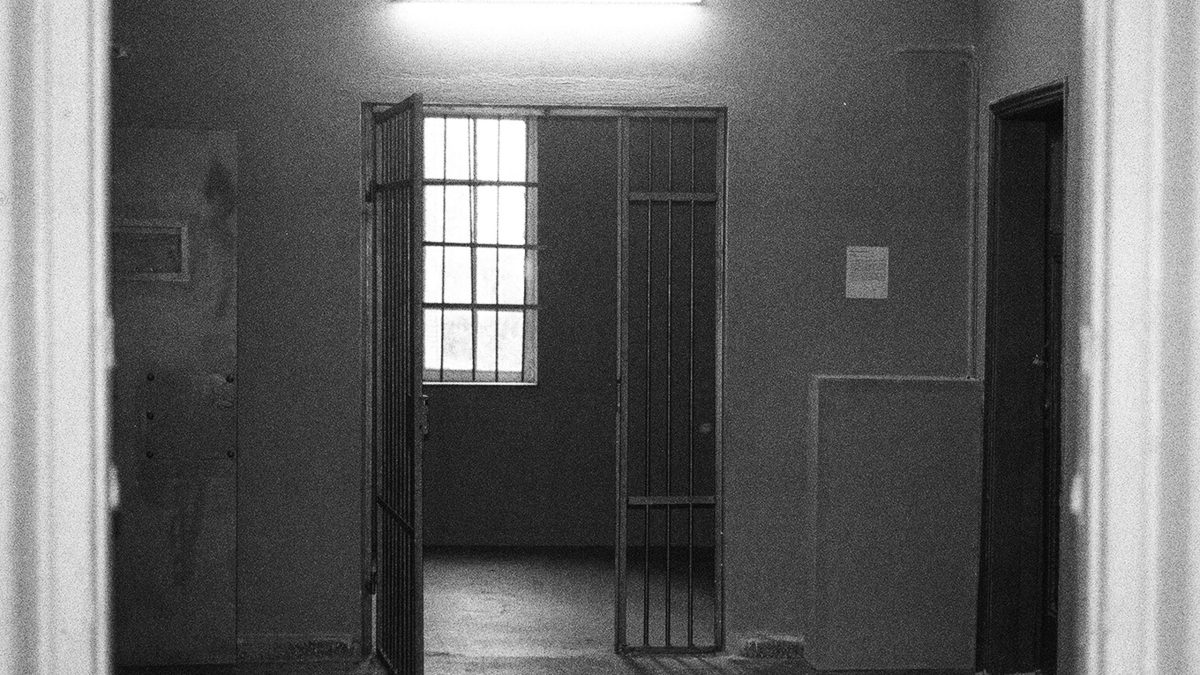

We visited Uncle Ricky in prison often when I was a kid, and, after my family left Virginia in 2001, we saw him every summer. These visits were best back in the 90s when the rules were looser. We played Snakes and Ladders and Candy Land. I could sit on my uncle’s lap and hug him freely. My grandma was often with us, or an aunt and cousin. I didn’t mind the experience of being patted down, going into a private lady’s room with a guard and flashing my belly. Or walking from barbed wire building to barbed wire building while stifling my desire to wave to the men holding rifles on the roof tops. I loved sitting at the small plastic tables with my uncle and gorging ourselves on vending machine food. We always had a Ziploc bag filled with quarters so Ricky could have anything he wanted. He always wanted a cheeseburger. My sister and I would fight over who got to microwave it for him.

We also talked about my cousins who found themselves in trouble with gangs and drugs. Uncle Ricky often voiced his regrets about his past, and wished the next generation in our family would see how his life had been wasted in prison and choose differently. Ricky said if he could, he’d go back and do it all over, but that was nonsense. This was his life now. He would be in prison until the day he died. It wasn’t all bad though. He had people inside that were his family now, too. He’d found God and had become a Christian. It gave him a feeling of a spiritual existence beyond the prison. It made his struggles have purpose. It wasn’t a particularly happy life, but he’d made his peace.

Daisy and I arrived in New Haven in February 2023. We met Daisy’s mom for lunch at a Thai restaurant in town. She’d been diagnosed with a rare form of uterine cancer and was set to start chemo the following week. I thought of my uncle having been sick inside a prison. Who took care of him? I wondered. Were people kind?

Lily had been receptive to me reaching out. “Somebody has the power to let your uncle out of prison,” she told me over the phone. “We just need to figure out who that is.” I’d called her as soon as my uncle and I were disconnected. She asked me to collect every lick of information on Ricky I could find: his charges, his medical records, any reports of the three-strikes mess. My aunt sent me his entire digitized file, which I combed through obsessively.

I had just received an email update from Lily before we met Daisy’s mom. She had reached out to a few organizations and spoke with an attorney from one called Families Against Mandatory Minimums, who outlined the different types of parole and clemency options available in Tennessee.

Lily learned that medical furlough was only granted to individuals diagnosed with a terminal illness and less than a year to live. The more realistic options for my uncle would be executive clemency based on illness or geriatric parole. For clemency, the state wanted evidence that the applicant not only had a serious, life-threatening condition but has also made significant progress in self-improvement and could be trusted to live lawfully after release.

Geriatric parole was another route available to people over 70 who have chronic, incurable conditions that suggested they were unlikely to live much longer. However, individuals convicted of murder or violent sexual offenses were ineligible.

Lily told me there was a complication: my uncle was serving time for a charge labeled a “Crime Against Nature,” which historically has referred to some type of sexual offense. “It’s unclear whether this would fall under the category of a violent sexual offense since the statute may be outdated or no longer exist,” she wrote. At the end of her email she asked me to find out more.

Over spring rolls, I told Daisy’s mom that I was trying to help my uncle get out of prison. I said he was sick and that he’d only been given only a few years left to live. “He had cancer,” I said. Looking for a way to connect. To stir up empathy for this convict and his crimes. I wanted to humanize him. He’s like you.

“Well,” she said, grimacing and putting her hands up. “He did the crime.” It was not cruel. There was a tone of regret, and the question, what can you do? I thought of phrases she didn’t say but didn’t need to, like, suffering the consequences of one’s own actions. I knew that focusing on the decisions my uncle made as a stupid kid allowed for a feeling of justification. Plus, we can’t be sorry for everyone. We can’t let in all that grief. We can’t! Or we might have to look at the whole and ask why these systems of punishment make no effort of rehabilitation. Why our government would rather spend $44,000 annually to house an inmate when allowing them to live in halfway houses or simply supporting them as they get back on their feet freely are both cheaper options than prison. Why there is no culture of forgiveness for our former or current inmates. Why even the word “inmate” strips away any feeling of sympathy.

When I first went through my uncle’s file, I found his commutation letter, a personal reflection required for resentencing requests. It was from 2020, handwritten and scanned. “Now at the age of 67, and having lost 44 years of my life to incarceration, it is extremely easy to recognize what a wasted life I’ve lived,” he wrote. “The maturity which has emerged during my life has brought the realization of my failing to live up to who I could have been as a productive citizen and human being.” I couldn’t stop crying all afternoon.

I won’t romanticize the idea of who my uncle could have been or what his life would have amounted to had he not spent the last four decades in prison. It would have been humble. It would have been raising his son with his partner, whom he loved. Who he still calls and speaks to. His life would have been working the shipyards and manual labor. Paycheck to paycheck. He would not have been college-educated or the CEO of some company. But had my uncle been given a shorter sentence from the get-go, rehabilitated, and then released, he would have been kind. I believe that. He would have stayed close to my family. He would have had a good, happy, vibrant life.

And, despite his crimes, every last one of them, I still believe he deserves that.

There is no culture of forgiveness for our former or current inmates.

That week, I couldn’t stop thinking about a memory from when I was nine years old. My family had recently moved to Colorado. My Uncle Ricky, in place of seeing us regularly during visiting hours, started writing us all letters. He always sent us birthday cards, and once over the stretch of a year, he sent me and my sister dozens of Whoppers candy wrappers, flattened and empty, each with a promo running on the back—250 points could buy one movie ticket. 500 could buy two.

“I’ll never eat another chocolate malt ball again,” he told my mom over the phone when he’d successfully sent us enough for two tickets. Do you know how many bags of candy he’d had to buy from the commissary to send us to see Shrek? How much of his own money he’d had to spend while making pennies at his prison job? Or spending the small amount of money my aunts rallied to send him each month? How precious and generous that was?

I should tell you one more thing about my uncle’s first robbery. I’m sorry it’s late. I was scared to tell you before, worried he’d lose your empathy. When my uncle robbed that ice cream shop in 1973, he made the cashier perform oral sex on him. That’s what Lily was referring to on his record as a “Crime Against Nature.” I’d never heard this until I’d had to ask him what it meant.

What do we do when our loved ones fuck up? When they fuck up in ways that don’t align with our morals? I believe that those who commit sexual assaults should be held accountable. I believe in the trauma that survivors experience long into the future. I think of this woman and I wonder how this changed her. What is her name? What is she doing right now? Of all the things my uncle has done, this one challenges me the most. Of all the things my uncle did I know that this one challenges him the most too.

“There is no excuse,” he told me over the phone. His voice was sorrowful. “I feel ashamed. I regret it deeply. I was so young and stupid. At that moment, my adrenaline was so high.” I imagined my old uncle furrowing his brow, shaking his head. Leaning up against the wall, as he used the telephone in the common area, thinking of a mistake he made 53 years prior. “It’s a stain upon my life.”

I tried to have empathy. Couldn’t I remember being young and reckless? Feeling hopeless? I thought of that precise moment in my uncle’s life as an example of what humans will do for a false sense of power when they’ve lived their lives without it. I agreed with my uncle when he said there was no excuse for his behavior. And still I believe he has paid for his mistakes with the last four decades of his life. How do we talk about rehabilitation in this world? How do we say it was a mistake never made again? The robberies, yes, those went on. But he never committed any other sexual assault. Nor battery or murder. Never another person physically hurt. Nobody touched.

Lily continued to be helpful. She didn’t think any of the new details meant that my uncle didn’t deserve to be released. “This is now a 70-year-old sick man,” she told me. “He’s already spent 44 years of his life in prison. He doesn’t need to die in there to learn his lesson.”

We carried on, emailing organizations in Tennessee that might be able to help. There were many dead ends. Many more ghosted Lily, even though she was writing as a lawyer and not my Uncle Ricky reaching out as an “offender.” She told me she was getting frustrated by the discourteousness. That it took no time at all to respond and say, “Sorry, I can’t take on the case.”

Uncle Ricky told Lily that he prayed for her every day. He was extremely grateful for her hard work despite our no luck. To help, Ricky had friends looking into other law schools. It was a whole machine, trying to do research from within the prison, and keeping us all in touch. “I trust God’s plan,” he told me every time I spoke to him on the phone. But I could hear the restlessness in his voice. “Whether that’s my dying here in prison or being a free man.”

Then there was a small hope. In early 2024, Lily emailed me and said that Choosing Justice Initiative seemed interested in my uncle’s case. They had emailed her back and asked follow-up questions. It was an organization Uncle Ricky had asked her to reach out to. I read through their website: A Nashville non-profit law firm working to end wealth-based disparities in the criminal legal system. It was the most hopeful Lily had been all year. I felt hopeful too. I gave her all the information I had to help fill in any gaps. I called my aunt in Virginia to fact check. Lily sent it all over to the org. Fingers crossed, she wrote.

Once the three-strike rule was applied to his case, my uncle lived under the impression that he would die behind bars. It took hard work and a lot of time to accept that fate. For a majority of those years, he lived in a prison close to most of our relatives. He had regular visitors. He was never out of our family’s reach. When my grandmother passed away in 2010, three of my aunts sat at a table across from him and broke the news in person. They shared their grief for two hours. But when Ricky’s brother died in January of 2024, he received the news via phone call, all alone. I pictured him in his cell, his grief as big as a house. It was my uncle’s dying wish to visit Ricky one last time, but Tennessee was too far, too hard to get to.

Aside from that, Ricky knew the Virginia prison he was in for decades. He’d learned the ropes and had friends. He’d gotten diagnosed with cancer there, received treatment, survived, had open heart surgery and recovered in those walls. It was a place he knew as home. My uncle’s parole from Virginia may have given him hope he might live as a free man again, but it also isolated him from our family and completely uprooted his life.

Sick, he was placed in a special needs facility with men he had no history with. He received almost no visitors. He remained hopeful, wishing, yearning that the courts of Tennessee will have it in their heart—in their humanity—to let him live out his last few years a free man. I wondered if the hope of freedom had destroyed his peace. I wondered if it was worth it to be paroled at all if my uncle dies in Tennessee. You win, I wanted to tell the state governor, the district attorney general, the courts. He gave you his life. Give this man a free death.

“God’s plan” my Uncle Ricky said. Every time we spoke. “It will be up to God whether or not I walk out of here.”

Daisy’s parents are both doctors. They told me that after med school, when they started working in hospitals and losing some of their patients, they had to find a higher power and give up the arrogance that they could save everyone. God’s plan, God’s will, whatever you want to call it. You have to put it in someone or something else’s hands, or you’ll drive yourself mad. I thought of this every time my Uncle Ricky hung up the phone or signed off on his letters. I wondered if him keeping his faith is equivalent to keeping his sanity.

So, I started praying with each email sent out, each letter written. I lit a candle in my apartment. I bowed my head. I gave it to something bigger than myself.

Choosing Justice Initiative eventually emailed back in April, 2024. The email was four paragraphs long. Robust. But it was bad news.

How do we talk about rehabilitation in this world? How do we say it was a mistake never made again?

“IMO, it will be hard to convince prosecutors in East Tennessee to have any sympathy or mercy for him,” the lawyer wrote in her email. “I expect they’ll look at his story and see a man who escaped from prison and went on to commit a string of violent crimes in other states. They will not view the amount of time he spent in prison in VA without parole eligibility as any kind of injustice.”

I was bruised by the response. Lily didn’t forward me the email for two days, because she said it had felt hurtful to her too. She asked me to tell my uncle the news, so I wrote him a letter explaining the situation. I was not as harsh in my language. I didn’t say that Choosing Justice thought prosecutors wouldn’t have any “sympathy or mercy” for him. That in this woman’s honest opinion, the courts will not see a man who escaped and was done wrong by the Virginia courts, but rather a man that escaped and then went on to commit a “string of violent crimes.”

I tried to calm myself down by considering the number of cases that showed up on Choosing Justice’s desk. The amount of people, just like my uncle, asking for help. “In a world of endless resources, I’d be happy to take on his case,” the lawyer wrote at the end of her email. But in this world—where money was tight and they must make decisions based on lack—they could only take on cases with the highest likelihood of success. I thought of my uncle’s robberies—crimes that also took place in a world where money was tight and decisions were based on lack. I wanted her to see the irony of that.

At the end of my letter, I told my uncle I was still holding out hope. However small. Regardless of how long it took. There was nothing left to lose in knocking on doors, sending the letters, even if we had to put together the clemency application on our own. I signed off to my uncle with the phrase, “I put my faith in God’s plan.”

It took another six months before we heard a “yes.” It came from a professor at the University of Tennessee, who agreed to assign law students to Uncle Ricky’s case. “How could we not jump in?” she wrote in her email. “It is a heartbreaking situation and, while I’m not sure we have the answers, we can certainly look.”

I cried with relief at these words, and anxiously waited four long days until my uncle called and I told him the news. “I can’t believe it! I just cannot believe it, Michelle!”

Before we hung up he asked, “Will they visit me?” And I felt his loneliness reverberating through the phone lines.

Ricky’s still in there. Waiting for the law students to collect all the data, to make their case, but it’s coming. For now, we do our best to get by, and hold on to the possibility of something good. Freedom. A bedroom in his sister’s house. Driving a car. Grocery shopping. Cooking his own meals. Going to a movie theatre. Walking for as long as he wants in nature. Seeing a body of water. Swimming in it. I picture this. My uncle sun-kissed and wrinkled, standing in the sea. And I hold the belief in my heart that it will be true.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.