Nonfiction is a strange, alchemical business. In the knowledge that a good writer can make any subject sing, one of the books I’m looking forward to most in 2025 is The Season: A Fan’s Story (W&N, November), in which Helen Garner watches her grandson, Amby, play Aussie rules football during one Melbourne winter. Such territory sounds, I know, slight and even parochial; on paper, I have less than zero interest in footy down under. But this is Garner we’re talking about: Australia’s greatest writer of nonfiction. It’s certain to be epic.

November, though, is a long way off. Get a more immediate fix of Garner with the first UK publication of her collected diaries, How to End a Story (March, W&N), a book that concludes with one of the most candidly brutal accounts of the end of a creative marriage I’ve read. And if you’re in the market for memoir – diaries being autobiography’s first draft – some good ones are en route. I’m eager for Adelle Stripe’s Base Notes: The Scents of a Life (White Rabbit, February), an olfactory account of growing up in the north of the 1980s; Joe Dunthorne’s Jewish family memoir, Children of Radium: A Buried Inheritance (Hamish Hamilton, March); and Geoff Dyer’s Homework (Canongate, May), a portrait of the author as a working-class boy who keeps passing exams.

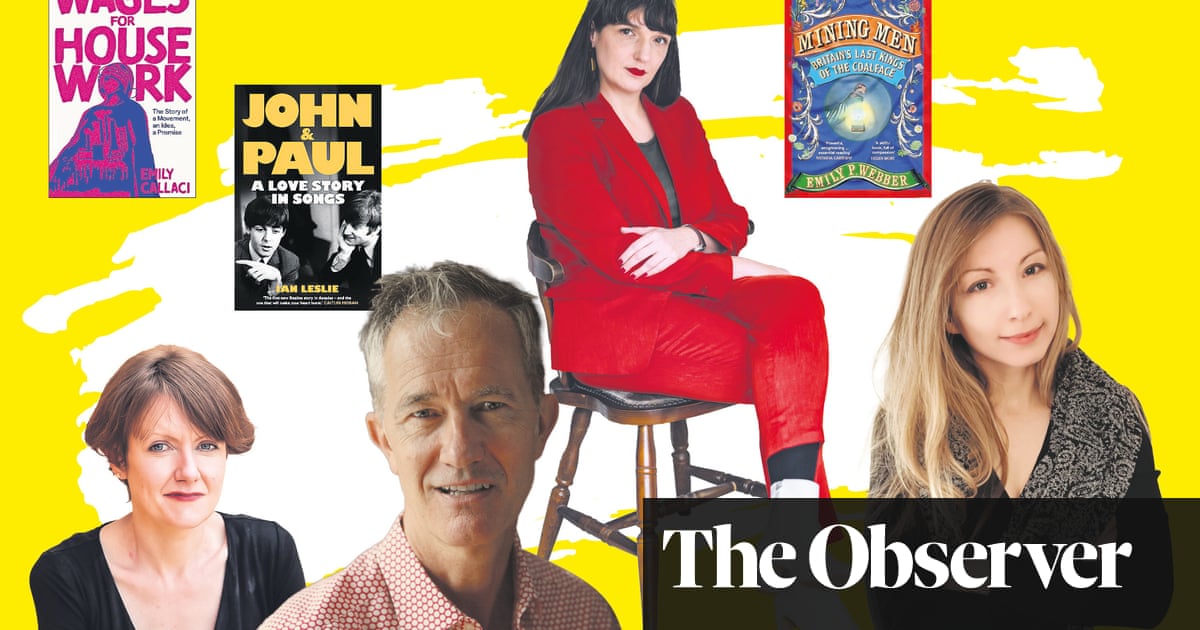

Adjacent to such individual stories, but equally rich, is Mining Men: Britain’s Last Kings of the Coalface (Chatto & Windus, February) by Emily P Webber, in which the author, a historian, deploys interviews and archival research to situate the strike of 1984-85 in a longer history of an industry that only 50 years ago still employed more than 250,000 workers.

Many of next year’s popular science books sound on the thin side to my ears, and somewhat derivative to boot. So let me just pick one: Music As Medicine: How We Can Harness Its Therapeutic Power (Cornerstone, January) by the American-Canadian neuroscientist and musician, Daniel Levitin. It comes with quite the jacket quotes. “For many years I’ve wondered why a bunch of frequencies organised into a piece of music has the ability, even without words, to make the listener cry and become emotional,” says Paul McCartney. “Dr Levitin… has some fascinating insights into this great phenomenon.” While we’re on McCartney, incidentally, there’s major excitement in our house about Ian Leslie’s forthcoming John and Paul: A Love Story in Songs (Faber, March). Leslie is such a good writer and thinker. I predict his analysis of Lennon and McCartney’s volatile relationship (a quasi-marriage?) will be a Beatles book for the ages.

Looking at Women, Looking at War: A War and Justice Diary is a vital work of reportage by the poet Victoria Amelina (William Collins, February), who died in July 2023 after a missile strike on the restaurant where she was eating in Kramatorsk, Donetsk. Comprising interviews with women (journalists, lawyers, human rights defenders) whose job it is to document war crimes in Ukraine as the war with Russia grinds on, it might usefully be read in conjunction with Kenneth Roth’s new book, Righting Wrongs (Allen Lane, February).

Roth, the director of Human Rights Watch for three decades, examines repression in countries such as China and Rwanda, highlighting the (perhaps surprising) power of “shaming” as a response to state brutality. Meanwhile, in 30 Londres Street (W&N, April), Philippe Sands, the lawyer (he has acted for Human Rights Watch) and prize-winning writer, draws out the nefarious ties between the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet and the SS officer Walther Rauff, who fled to Chilean Patagonia from Germany after the war, in another of his utterly gripping narratives.

Three books by Andrea Dworkin – including her first, Woman Hating – will be re-issued in February as Penguin Modern Classics, an accolade long overdue. And for readers keen to revisit second-wave feminism, other options are available. I like the sound of Wages for Housework: The Story of a Movement, an Idea, a Promise (Allen Lane, February) by Emily Callaci, a professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Wages for Housework! was a global movement of the 70s, as feminists across the world called for care to be rewarded just as production is, and reading about it now is bound to be both energising and salutary, so much lost as well as gained for women in the years since. As if to underline this, Victoria Smith, the author of Hags, also returns in 2025 with (Un)Kind (Fleet, February), a timely account of so-called kindness culture, and all the ways in which it conspires against women.

Is biography, lately rather down on its luck, due a comeback? When Sue Prideaux’s daring new life of Gauguin made the shortlist of the 2024 Baillie Gifford prize, I suspected that it might be, and the evidence so far is encouraging. In the summer, Michael Haag will publish a new life of that most unfashionable of writers, Lawrence Durrell (Profile, July), while in Hidden Portraits (Faber, March) Sue Roe reappraises the lives of Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot and four others, all connected by their relationships with Picasso.

Francesca Wade, the author of Square Haunting, returns with Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife (Faber, May), and Frances Wilson, whose recent life of DH Lawrence was so extraordinary, will publish Electric Spark: The Enigma of Muriel Spark (Bloomsbury, June). Dianaworld: An Obsession by Edward White (Allen Lane, May) takes a kaleidoscopic look at Diana, Princess of Wales, via her in-laws, her servants, and her fans. Not quite biography, but almost, is It Used to Be Witches by Ryan Gilbey (June, Faber), a book that celebrates the outlaw spirit of queer cinema from the 1950s on.

Finally, to one of the big publishing events (if not the biggest) of 2025 – a new book by Robert Macfarlane. In Is a River Alive? (Hamish Hamilton, May) Macfarlane answers the question of his title with a loud yes as he travels from northern Ecuador to southern India to north-eastern Quebec. In each place, beautiful and miraculous waterways are under threat, and must urgently be defended. Personal as well as political, it’s almost as certain to shift readerly perspectives as it is to be a bestseller.