The humble comma, normally so easily overlooked within a page of text, is clearly Charlie Porter’s weapon of choice for his debut novel. Here, he wields it to propel his narrative forward in the kind of urgent, endless staccato rush that sometimes requires the reader to look briefly up and away, if only to gulp at some fresh air.

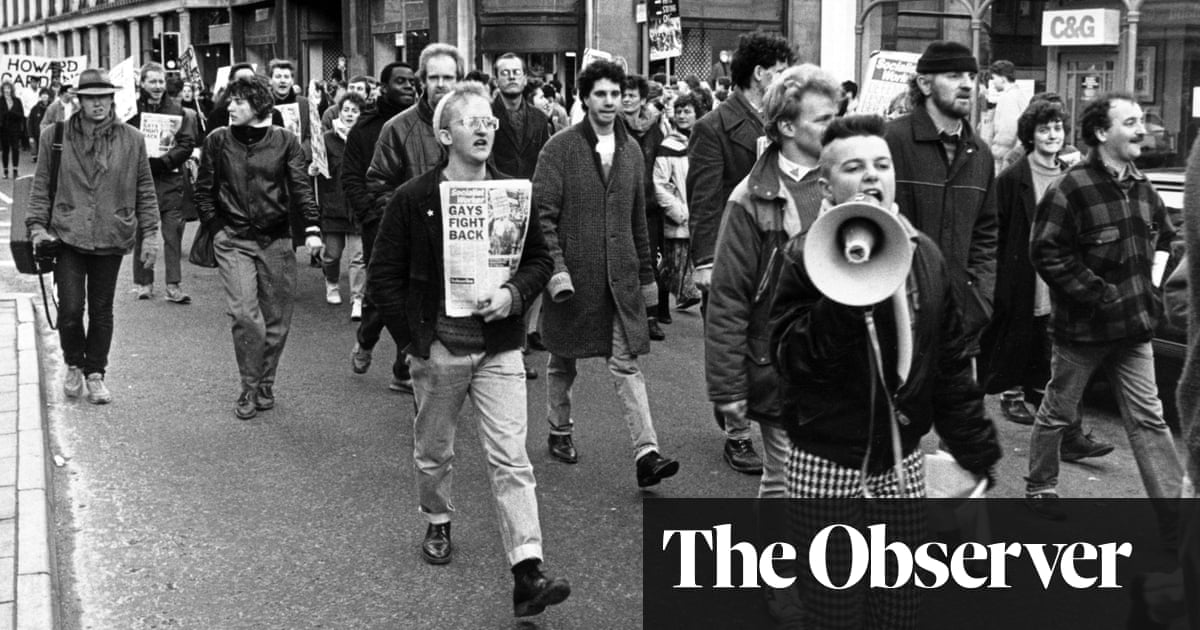

Nova Scotia House, the 51-year-old journalist’s first work of fiction after two books on fashion, tells the story of living through the Aids crisis of the 1980s and early 90s, and how those who survived it will be forever accompanied by the ghostly presence of those who didn’t.

Johnny is 19 years old when he meets Jerry, 45, the older, wiser guide who introduces his young charge to London, the gay scene, and a sense of community – a queer community – he has long sought. In his first nightclub, for example, Johnny experiences “people more people, noise like I had not known it, a hard wall, relentless, so many bodies, light mostly red, smoke steaming from bodies, smoke from cigarettes, chemical smoke in the air, Jerry grinning maniacal, in my ear he said, follow me, and Jerry took my hand…”

Jerry, Johnny says, “was the first man I loved, the first man I loved who died. If we normalise Jerry’s death, we eradicate Jerry. If we normalise the nightmare of HIV, we eradicate its victims.”

Porter tells Johnny’s story from the sober – and mostly sad – vantage point of 30 years later. He continues to live in Jerry’s flat, No 1, Nova Scotia House, not merely out of sentiment but because he never quite got his act together enough to leave, and move on. We don’t learn what it is he does for a living, but are instead given the sense that life is passing him by, and that most of his connections now come via dispiriting hookups found on his phone. “Will I see anyone. Don’t care. Sounds rude, it’s not rude.” Mostly, he pines for something deeper, but this he feels is impossible in a city ravaged by redevelopment, obliterating existing neighbourhoods and pricing out natives. Still, he tries. “I want a beer and I want that guy to come over and I know he won’t come over so why do I bother when I know he won’t be coming over. The game is the game. Can I get out. Do I want to get out.”

Nova Scotia House is intensely claustrophobic, its jittery rhythm an incantation to all that we can lose in life, even as we are still busy living it: youth, hope, optimism, alongside the helpless yearning for a better tomorrow. Its pages are steeped in alienation, and soaked in melancholy. What is it like, Porter posits, to be almost 50 and still feel that the world around you remains so cursorily hostile? How do we maintain our tribes?

But while the writing style can seem suffocating, there is purpose to it. It pulls you in, then holds you appalled, hypnotised. It is of course the critic’s bad habit to read autobiography into fiction, but Porter has conjured such intensity here, and such tangibly real characters, that it feels like the gospel truth. This is a book that works both as a tribute to those who died of the cruellest disease, and as a more general lament to love, loss and remembrance. It is profoundly, bracingly human.