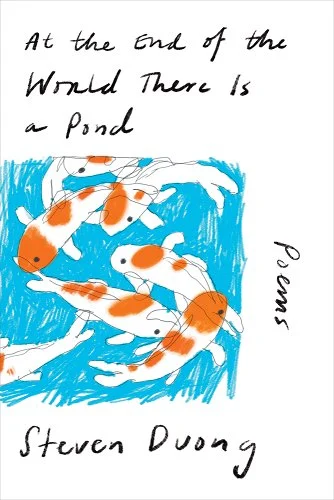

Steven Duong’s debut collection, At the End of the World There Is a Pond, is born out of his obsession with the idea of containment, both of nature and as a second-generation Vietnamese American.

Bridging the esoteric and the intimate, his poetry grapples with questions of the self in the context of familial and literary ancestors. An Iowa Writers’ Workshop graduate, he negotiates ghosts, memories, fiction as meta-narrative in poetry, and the legacy of the Vietnam War for the Vietnamese diaspora in America.

Duong and I spoke on video chat, discussing his connections to the past—ancestral and personal—and how these connections play into his relationship to himself as a Vietnamese American writer and poet.

Sanchari Sur: We should talk about the title. You seem to be saying that at the end of the world, instead of quiet, there is going to be an excess of life. The way you write about water throughout the collection, there’s an excessive flow of water which tends to overflow without regards to boundaries. What is your connection to the imagery of water in your work?

Steven Duong: In something about the pond, there’s this sense of the pond in literature, maybe just in our contemporary consciousness, as being this inert, still, peaceful thing. So, at the end of the world there is stillness, life is gone, things are now inert, but I wanted to counteract that because ponds are such lively places beneath the surface. There is a line in “Novel”—the first in a series of sonnets: “an image in a pond/ made foreign by the mouth breaking its surface,” where I have the pond as this thing with a surface that can constantly be broken. And to enter the pond, you need to break that surface, disturb it, create those ripples. For me, the pond feels very connected to these other bodies of water throughout the collection.

I have this lifelong fascination, obsession, with fresh water aquarium fish. I kept them throughout my life. My dad and I had a fish tank growing up, and my brother had one as well. But there’s something about the way we try to contain these animals, removing them from their natural environment, something like a pond or a river or a lake, and transferring them to a place to be contained and observed. That human-imposed containment is what drives a lot of the poems.

In “Best-Case Scenario”—an after apocalypse scenario—underwater things are drowned and submerged, but there’s also color and a lot of life and a lot of movement in the absence of people. I see the end of the world as not the end of living things in community with one another. Maybe, the idea of the fish tank is to create this natural simulation of animals, or habitat, but so often, we end up having fish from Southeast Asia and Africa, and the African Great Lakes, all in the same aquarium. There’s a simulation of nature, but also of being forced into community with one another. I think that’s also kind of what diaspora is. Diaspora is, by nature, forced because of war, migration, displacement. That forcedness also brings everything together into the pond.

SS: Let’s talk about a different arc in your collection. One of the arcs was the “Novel” poems scattered throughout. They seem to be about a journey of a writer between irreconcilable things bubbling up. Can you speak to this meta-narrative about writing, and why instead of putting them together like your “Tattoo” poems, they are scattered?

SD: I went back and forth with both of those sets of sonnets. The way these ended up featuring in the book, they mirror these two different artistic practices that I have, which are, fiction writing or writing this novel, and the other is tattooing. It so happens that with each of those “Tattoo” poems, I wanted to speak to one particular experience or one tattoo session with a specific person. And these kind of happened in quick succession in the span of maybe a few months. Whereas, these “Novel” poems, I wrote the first one in the winter of 2018. The final “Novel” poem—“Novel (Not even in my dreams…)”—is the last one I wrote for this collection. I’ve been writing a novel this entire time and I’ve used the “Novel” poems as a way to speak to the process, the frustrations, the difficulties of fictionalizing a life, or creating a character that is not exactly distant from my own experiences and identities, but is distant enough that they can be separated by this veil of fiction. I think I needed that distance between the poems too. I wanted the sense that a novel is being written as the collection proceeds, like accruing.

Novel-writing is so different from writing a poetry collection. In writing a poetry collection, there is a sense of accumulation and accrual, but there’s so much curation. Like, you have written 100 poems and are trying to fit 40. Whereas with this novel, it feels like a document that’s accumulating ephemera and characters and ideas and dialogue. I wanted the fictional novel within the universe of the collection, like these sonnets, to feel like they’re growing. I am using the sonnet form as a hyper-concentrated box. And because the “Novel” poems are so hyper-concentrated, it’s like a box, making them suitable for this meta-fiction or meta-narrative.

SS: What is your personal relationship to tattoos and tattooing, and how does that reflect in your poems?

SD: My personal relationship with tattooing is kind of fraught. The first tattoo I received was on my eighteenth birthday. It was a contentious thing. With my family, there was this whole big fight, and I don’t want to get too deep into it, but it resulted in a lot of animosity and a sense of alienation with my family. Over time, that’s shifted and changed, but I guess my initial experience was this is such an individual expression of my creative desires and interests, and it was met with so much resistance and animosity from those close to me. As I have grown older, been tattooed more, and through my own tattoo practice, my relationship has changed. I’ve become a little bit less precious about them. I have worked with artists that I like. But as a practice that I engage in, I find it so rewarding. There are always those same kinds of questions that come up in every tattoo session with every new person, “What was your first tattoo? Is this your first time doing this? When was the last tattoo you received? What does it mean?” etc. I mean, those questions always arise, and then it always leads to these very interesting conversations when you’re sort of forced into intimate proximity with somebody. But people that are featured in these poems, some of them I know very well, and some of them were new friends. It allows you this intimacy in a really short amount of time, just because it’s such a physical practice. And it’s so much feedback. So, I am adjusting something so that this person is comfortable. So, adjusting the design and the actual line work, and the shading and the strokes, so that the person ends up with the representation that they’re pleased with. There’s so much give and take to it. In the same way with those “Novel” poems, where I wanted to capture something about novel writing in those poems in addition to their concerns with experience, identity, and how to lead a meaningful life as an artist or a writer, with the “Tattoo” poems, I wanted to capture that intimate experience with the person being tattooed.

SS: I want to talk about another theme in your work, that of addiction or pills, especially in your poems, the ghazal, “Ode to Future Hendrix in the Year of the Goat,” and “Oxycodone.” They talk about addiction as an act to escape in some contexts, and a lens through which to mediate the world in others. Can you speak to this theme?

SD: The experience of addiction and recovery are very individual, everyone has a different journey with addiction and recovery. But oftentimes, the recovery portion of it depends upon or requires community with other addicts, taking them with 12 step programs and other rehabilitative measures. But with these poems specifically, I wanted to speak to songs that feel like they are celebrating the experience of addiction. They’re taking the experience of drug use and substance use and creating a really pleasing image. An image that’s really beautiful and kind of scary and self-destructive. I mean, it’s an old trope, I guess, of the beautiful tortured artist. I was thinking of the song “Codeine Crazy” (by Future) with “Ode to Future Hendrix in the Year of the Goat.” It’s one of those songs that constantly lurches between this celebratory tone about wealth and drug use and sex. Then, in the space of like one or two lines, it lurches into this really dark and self-destructive and honestly quite tragic and insightful angle, and it becomes about addiction as opposed to being about drug use. And I kind of wanted to capture that here in poem alongside this image of the devil and hungry ghosts. I wanted to engage in the romanticization that these kinds of songs engage in while framing it as a blessing, or a prayer. This poem is about the art that comes out of addiction, and the “Oxycodone” poem is about the addiction experience itself. It’s more intimate, speaking directly to the drug. It is something Future does in their songs, personifying the drug. I wanted to write a poem of addiction that treats the drug almost in the way you treat a lover, or a long-time friend.

SS: In your poems, “Extinction Event #6 at the Shanghai Ocean Aquarium,” “Veneers” and “The Unnamed Ghost,” memory seems to play itself out primarily in terms of its transformative nature. However, there are fleeting instances of memory as they are encountered or reimagined by the speaker. There’s also an element of haunting that suffuses these moments in these poems. Can you speak to the function of haunting and memory in these works?

SD: My impulse to write about ghosts and hauntings probably has a lot to do with the religious practices in my family growing up. So, my folks are a variant of Buddhists, but there’s also this folk religion that we practice at home, sometimes referred to as ancestor worship. I hadn’t encountered that term until later in life after I had done ancestor worship for however long. But it’s this thing where you set out incense on the day of—let’s say—your grandfather’s death and for a moment while you are honoring this ghost with incense and fruit and offerings, you set the dinner table as if the whole ghost family is going to be dining there, wishing them well, and hoping that they’ll protect you. And then they vacate the seat, you take the seat, and you eat the offering. I hadn’t thought about it too deeply until later, after I’d stopped living at home. But I think I grew up thinking of ghosts and spirits as these entities that are loaded with significance for my family, but with me, there’s something casual about them. They visit on the same day every year, they have a routine, they sit down and eat. I didn’t know my ancestors but I wanted to engage with them on the page.

It’s a question for ethnic American writers or writers of diaspora, how do we honour and represent the stories of our ancestors? For me, there’s a big legacy of the Vietnam War, and migration and displacement that occurred during and after the war. Although it’s not explicit in a ton of the poems, I was interested in the ways that these spectral memories and ghosts can be present without necessarily taking over, like this Western idea of possession. It’s not like that, like they are there but they are—

SS: Copacetic.

SD: Yeah, exactly. I wanted that to be present in the poems. So, I am speaking about memory as if it was a ghost. It’s like giving form or giving shape to something very conceptual and abstract like its personality or personhood is one way to sort of make sense of it. It also ties into these ideas of containment, and how do we find forms for stories that we can’t tell otherwise?

I’ve been teaching poetry and fiction to undergraduates over the past couple of years, and I often talk about poems as ways to give shape to something that is formless, but just for a moment. You’re giving it enough shape to exist for the span of the poem, and then once the poem is done, the barriers break, and the formless thing becomes formless again.

SS: Another theme that stands out is that of reification or transformation in poems such as “Anatomy,” “Ordnance,” “The Failed Refugee,” among many others. Can you speak to the way the past functions for you as a poet and the way you write it into your poems?

SD: Growing up, the past was something very rigid. The way the Vietnamese diaspora in the States understands Vietnam after the war is, we had a country called Vietnam, and when Saigon fell and the northern communist regime took over, that was the day we lost our country. That’s the language they use, the language of loss of a country that we had and no longer have. It almost feels like the narrative of post-Civil War South. Like, this was a way of life and now it’s no longer there. So I grew up understanding that past, the Vietnamese past, as gone, and if you were to go to Vietnam, it’s a different place completely. Some of these poems that are set in Vietnam or engage with some of my travels in Vietnam, I began to realize the road between the past and the present is continuous. It’s not straight, but continuous, and that it didn’t stop existing when all these people left. There’s also a sense too while growing up, that we have to preserve our language. And I think that’s important to ensure that future generations in a diaspora have access to the culture of their home countries, etc. But there was a sense of, ‘we are the ones preserving it,’ when there’s an entire country that speaks the language.

But a big part of the way my poems in this collection deal with the past is that it once felt rigid but is now able to be transformed or revived into something new. In “The Poet,” I was thinking about this poem by the Vietnamese American poet, Hai-Dang Phan, one of my first poetry teachers. His book, Reenactments (2019), deals with the legacy of the Vietnam War and war re-enactments in ways to represent the history of conflict and war. Some of those poems deal with civil war re-enactments, but some of them also deal with Vietnam War re-enactments. The work of Diana Khoi Nguyen treats the past as not this inert thing but this malleable, living, evolving organism. Also, Toni Morrison and her representation of the past and different manifestations of the history of slavery and slave trade in the U.S. I feel it’s easy to sometimes view these histories as trapped in a museum or whatever. But I think it was important for me in my poems to write about the past as an alchemically unstable substance.

SS: I am curious about your poem, “The Black Speech,” which seems to be a critical renegotiation of Tolkien, where you seem to be reclaiming the seemingly racist legacy of the Lord of the Ring movies and his books with your own memories of The Hobbit, a gift from your Kung Fu teacher. Can you speak to your relationship with Tolkien in this poem?

SD: This poem begins with observation. I was in Thailand and I was traveling with a friend. We saw this guy with the script on the ring around his arm. It gave me a space to talk about Tolkien and my relationship with fantasy novels. I grew up on Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and Piers Anthony. Part of what drew me to fantasy as a kid was the fantastical breadth of culture. Part of getting older and re-reading some of these, and also understanding the contexts in which they were written, is also understanding that part of this narrative of Lord of the Rings is saving the West from destruction against the forces of evil in the East. It’s not subtle! [Laughs] So, part of it is engaging with the fact that these things that are beloved to me are steeped in a white supremacist, sometimes Christian, worldview. But also these things gave me permission to imagine other worlds. And seeing somebody create their own languages, there was something really free and beautiful in that creation.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.