Mafalda is a young girl who hates soup and hypocrisy and loves democracy and the Beatles. She’s a precocious six year innocently questioning how the world works—often to the exasperation of her parents. She and her friends struggle to learn chess, try to become telepathic, and worry about war and overpopulation. After making a passionate plea for world she realizes that “the U.N., the Vatican and my little stool have the same power to sway opinion.” And she has the same hairstylist as Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy

Article continues after advertisement

Mafalda is the star of the titular comic strip, originally published in Argentina from 1964-73, newly translated into English from Elsewhere Editions, the children’s imprint at Archipelago Books, in its first foray into comics.

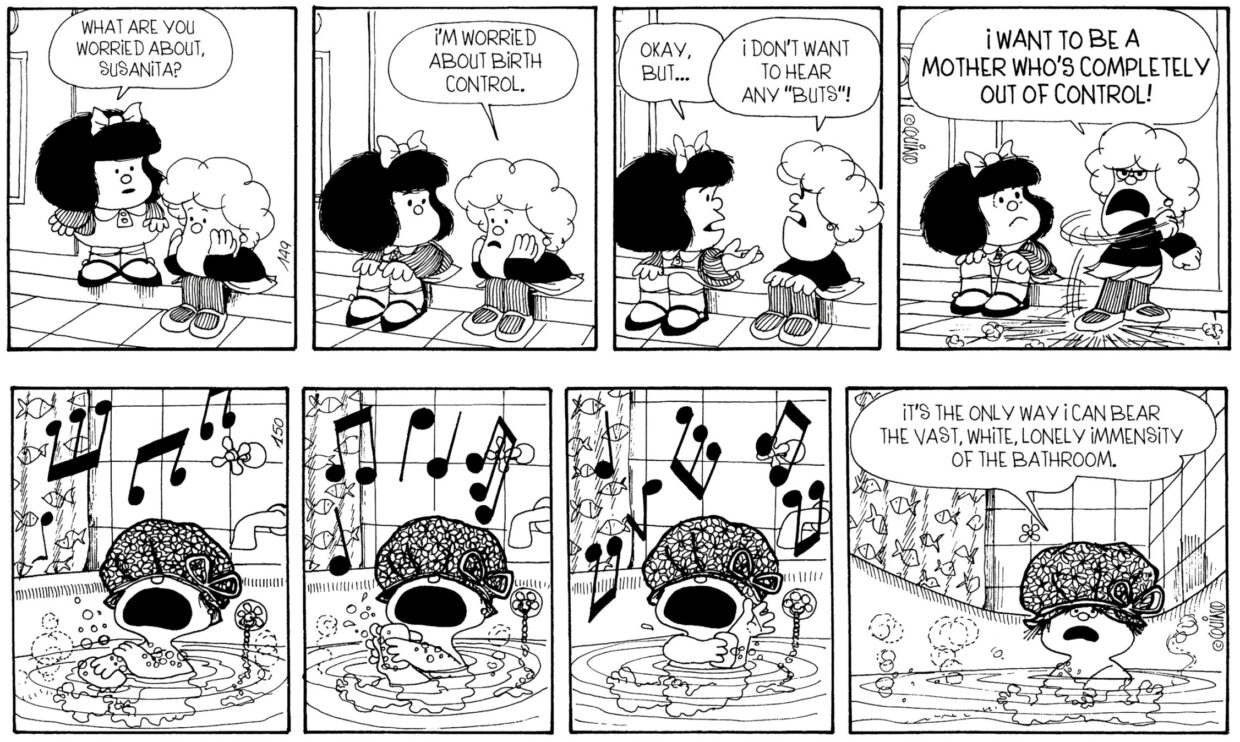

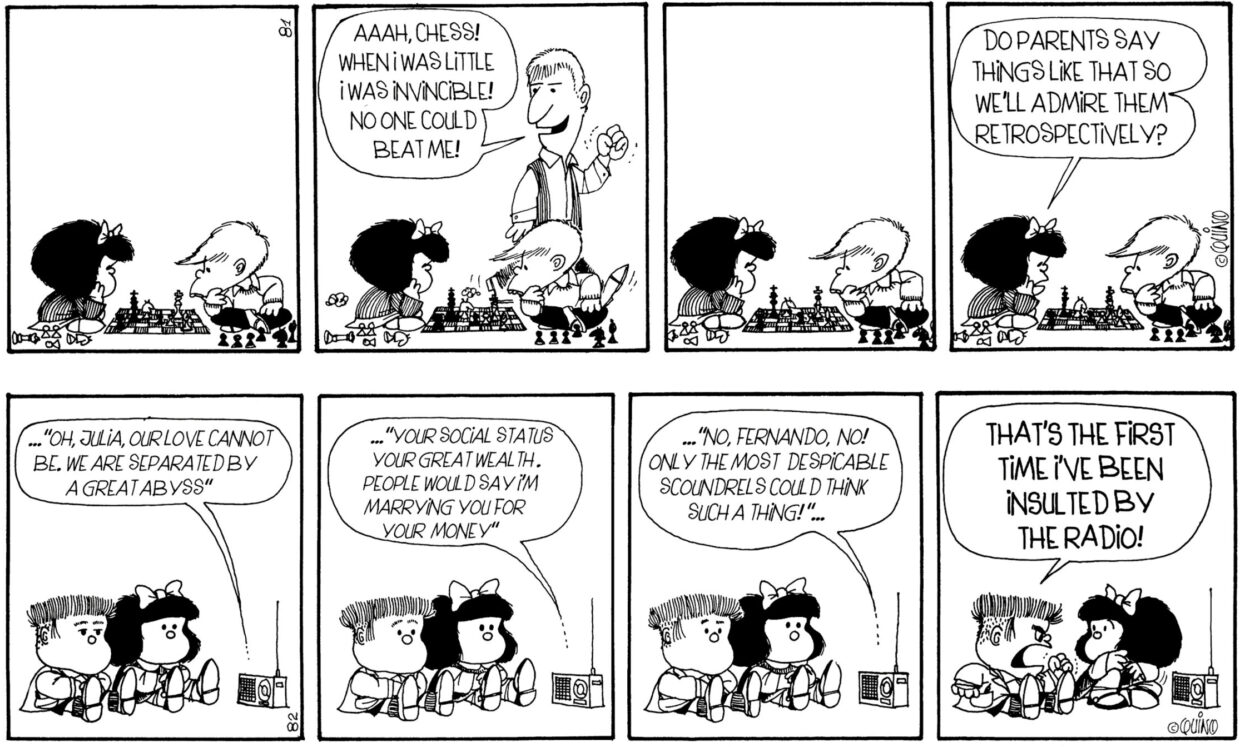

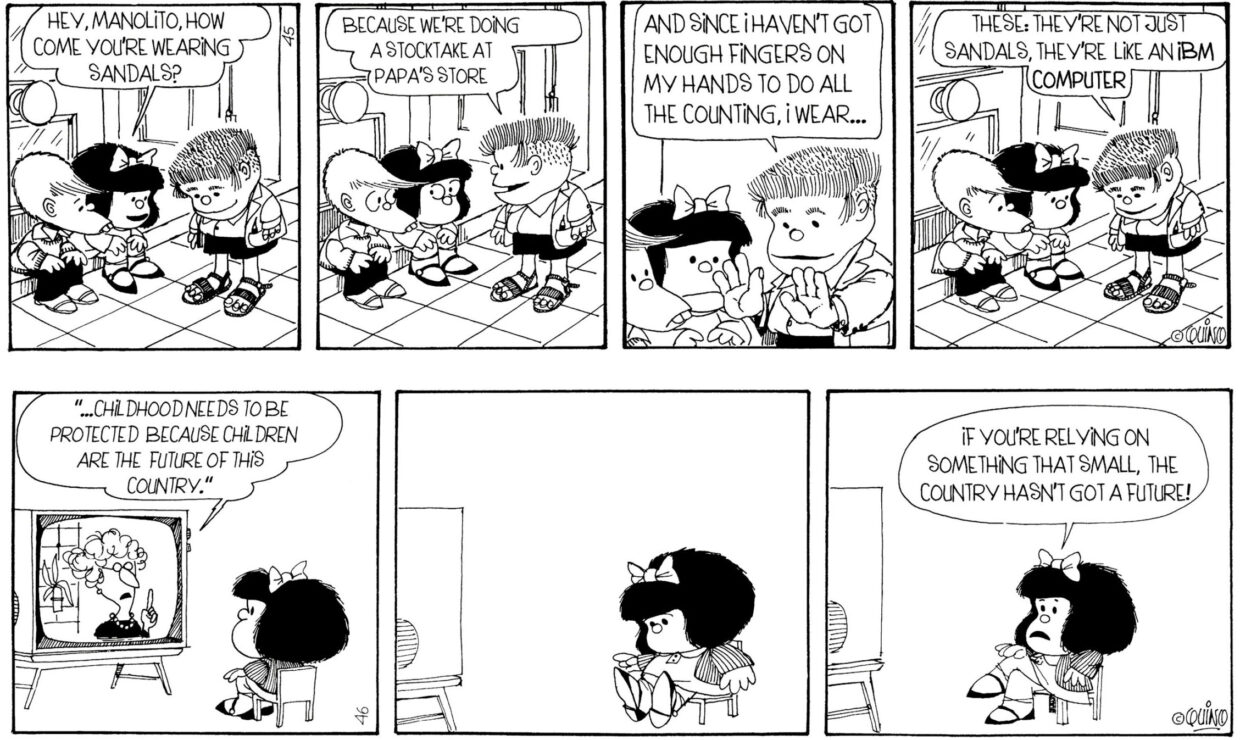

Mafalda has long been compared to Charles Schultz’s Peanuts. Both are aimed at children, but are complex enough to be appreciated by adults. Both are simply drawn, but never simplistic. The interactions of the child protagonists have metaphoric and politic overtones. The humor in Mafalda toggles from complex wordplay to visual humor to political allegory.

Mafalda is beloved around the world, too, around the world, particularly in Latin America, where she remains a powerful political image.

Umberto Eco called Mafalda a “hero of our time.” The Mexican writer Álvaro Enrigue wrote that “I understand the world, still, through the eyes of Mafalda.”

Mafalda’s creator, Quino, born Joaquín Salvador Lavado Tejón, was an Argentinian artist and cartoonist who, over the course of his life, produced a body of work that included cartoons, editorial comics, animation, and books translated into dozens of languages. He received honors from around the world including the Prince of Asturias Award and the French Legion of Honor. In an obituary for The Comics Journal, Juan Manuel Domínguez wrote that “For Argentina, he was both our [Charles] Schulz and our [Saul] Steinberg.” Which gives a sense of both his acclaim and his range. He was, as Liniers, the Argentinian cartoonist behind Macanudo, told me, the rare cartoonist “who could draw well and funny.”

“I was born after it ended, but when I was a little kid, the collections were everywhere. From my generation onwards, it’s how you learned to read,” Liniers said. “It was the first book that I really enjoyed on my own.”

Mafalda is a story of children, but it is also a deeply political strip. It’s this aspect which has dominated so much of the conversation around it over the decades. “I always described it as Peanuts plus socialism,” Liniers said. But it’s also more allegorical than other “political” comic strips.

“There was a strip where Mafalda has a turtle. And the name of the turtle is Bureaucracy. And so she calls, hey, Bureaucracy. And there’s six or seven panels where she’s just waiting. And by the end, the turtle shows up and she gives her a little piece of lettuce. I remember thinking that that strip was funny because the name was weird. I had no idea what bureaucracy was. She didn’t name the turtle Daisy or whatever. She called it Bureaucracy. That’s so funny,” Liniers said. “That’s the thing. He had all these different kinds of humor. It was a very, very smart strip.”

The political aspect is what has attracted so many to the comic strip. Umberto Eco wrote:

Mafalda is truly an angry heroine who rejects the world as it is. To understand her, it is convenient to draw a parallel with another great character whose influence is not alien: Charlie Brown. Charlie Brown is North American, Mafalda South American. Charlie Brown belongs to a prosperous country, to an opulent society in which he desperately tries to integrate himself, begging for solidarity and happiness; Mafalda belongs to a country dense with social contrasts, which despite everything would like to integrate her and make her happy, but she refuses and rejects all offers. Charlie Brown lives in a childlike universe of his own, from which adults are rigorously excluded (with the exception that children aspire to become adults); Mafalda lives in a continuous dialogue with the adult world, a world that she does not esteem, respect, that she renders hostile to her, that she humiliates and rejects, claiming her right to remain a child who does not want to take over a universe adulterated by her parents.

“Our publisher Jill Schoolman first encountered Mafalda while traveling in Buenos Aires,” Emma Raddatz, the Director of Elsewhere Editions, told me recently. “She returned with Quino’s Todo Mafalda, a 650-page dandelion-yellow doorstopper, and all of us in the office began paging through. From there I encountered her wherever I went. Whenever I mentioned her name to Spanish-speaking friends, editors, writers, their eyes lit up, ready to tell me all she meant to them.”

The comic is being translated and overseen by Frank Wynne, who for decades has been an award-winning writer and literary translator, but earlier in his career was a comics editor at Fleetway and Deadline magazine. “I first read Mafalda in French in France, because Mafalda was translated into French from the 1960s all the way through. I read all of Mafalda in French long before I ever learned Spanish,” Wynne said, speaking of the strip with the same excited and affectionate tone I heard from so many.

“I was very passionate about it. So much so that actually while I was editor of Deadline, I got permission to run a number of the four panel strips, which I translated myself,” Wynne said, remarking sheepishly that it was possibly illegal. “[Jill and Emma] couldn’t have known all of that, but they came to me and said, would you like to translate all of Mafalda? And while I did not actually give them my right arm since I needed to type, I might have done if they’d asked nicely.”

For Wynne, the translation has involved some challenges when it comes to the politics, but not in obvious ways. “There are lots of references to Vietnam in this. And lots of references to a lesser extent to the civil rights movement. But equally, I mention Argentina in it several times though Quino never mentions that she’s in Argentina,” Wynne said. “When they’re playing at her being president and Manolito and Philippe come in with toy guns and say, this is a this is a coup d’etat. And she says, get out, I have them say, that’s not how we do things in Argentina, Madam President”

“If you don’t say in Argentina, that doesn’t work,” Wynne said. “The notion that playing at doing a coup d’etat and expecting the president to behave in a particular way is something that only works in Argentina and they would have understood that then. I’m not footnoting. It is called it’s what’s called stealth glossing. You are adding a piece of information stealthily without actually saying, look, look, you need to know this piece of information.”

“For kids to get it, you need to do that,” Wynne said. “The thing is that kids will get this up to a point, but kids were never Quino’s primary audience. In the same way that Peanuts is not primarily for children.”

“Within the comic, the characters are different parts of Argentina,” Liniers said. Having grown up in Argentina, you can see both what the strip was at the time it was created and what it stopped being. “You have like the bourgeois with Susanita, you have the young rebel left wing with Guille, Mafalda’s brother. Manolito is this capitalist. And even with all this difference, they managed to be good friends, right? They sort of like each other sometimes. By 1973, I think Argentina’s society was completely fragmented. The extreme right and the extreme left had made those relationships feel almost impossible.”

Mafalda is timeless in so many ways, but I keep thinking about the ways that Calvin and Hobbes’ personalities were representations of their namesakes’ philosophies. I mentioned to Wynne that I thought of politics in Mafalda the way that I think of theology in Peanuts, which appeared in a variety of ways both overt and allegorical over the course of the strip. As if to prove my point, Wynne smiled and quoted a decades old Schulz strip where the punchline is Linus stating “hoping to goodness has no theological foundation.” Wynne smiled. “That is not a joke that a child would understand.”

Isabella Cosse wrote what is considered the definitive book on the strip, Mafalda: A Social and Political History of Latin America’s Global Comic. Translated into English by Laura Pérez Carrara, the book considers the strip from a variety of angles and how it became such a global phenomenon across generations. To see the strip as “a paper-and-ink creation that took on a life of its own and has become a global myth.”

Cosse argues that “the comic strip channeled a resistance to that order through a nostalgic echoing of the 1960s that asserted the continued relevance of that generation’s utopian dreams.”

She writes, “The comic strip offered a philosophical and atemporal reflection on the human condition, which also operated productively on decisive phenomena of the 1960s—authoritarianism, generational conflicts, feminist struggles, the expansion of the middle classes, and the challenges to the established family order.”

One topic I raised while talking with Liniers was Mafalda’s place in Argentinian comics, which is one of the great comic traditions in the world. The 1940s to 1960s are considered a Golden Age, with Argentinian cartoonists—along with artists from Italy and elsewhere who lived and worked in Argentina—producing comics that are still read the world over. For decades since then, Argentinian artists like José Muñoz have been among the most important and influential cartoonists in the world.

Liniers names both Mafalda and The Eternaut, which recently became a Netflix series, as two of the great comics to come out of Argentina during that era. “They are very different because one is a science fiction adventure with realist drawing, and the other one is a satire and a little kid strip. But in their difference, it kind of encompasses everything in the middle.”

It occurs to me that Mafalda and The Eternaut—and many other Argentinian comics—are deeply political works that use allegory and genre tropes in ways that suggest a conversation with Latin American magical realism. But in Mafalda, we see the world through children’s eyes, which make it new and startling.

“Mafalda spends a lot of time looking at the world and thinking, this makes no sense. But her approach to it not making any sense is much more adult than your average six-year-old—and frequently much more adult than the actual adults,” Wynne said. It’s this sensibility that shapes the comic.

Mafalda is such a singular character and a singular world. There is so much depth, so many kinds of humor, to be found in this simple looking strip. Throughout the writing and researching of this article, I’ve kept Mafalda on my desk and keep returning to it, flipping through it and reading strips at random. I have yet to get tired of it.

“Book two opens with a four panel strip of Mafalda standing on a stool holding a light bulb. And in panel two, her father comes in and says, what are you doing? She said, I’m Liberty. He said, well, who will you be if you fall down and break your neck? And she says, Liberty,” Wynne said. “There is a things will probably not get very much better strain in Mafalda. That is important,” Wynne said when we spoke about the comic.

Quino ended the strip in 1973 and with his wife, left for Europe. Many other writers and artists fled the country during this time. For years, Quino said that he quit the strip to avoid repeating himself, but in later years he cited politics as a reason for his decision. “After the coup d’etat in Chile, the situation in Latin America became very bloody,” he said in an interview quoted in his BBC obituary. “If I had continued drawing her [Mafalda], they would have shot me once, or four times.”

This was not paranoia or self-aggrandizement. Liniers named The Eternaut as the other great comic of that era, and its writer, Héctor Germán Oesterheld, was disappeared by the regime along with most of his family in the 1970s.

As an adult in 2025, it’s hard to separate the comic strip from these events. Mafalda was a symbol of protest against the military regime. One image from the comic was reproduced and used in protest posters for years afterwards depicting Mafalda pointing at a police officer’s baton, calling it an “ideology-denting stick”.

The real life politics—then and now—that these comics reflect are unavoidable. I grew up with Calvin finding an injured bird, the deaths and bullying and other events of Funky Winkerbean, Farley dying and Lawrence coming out in For Better or For Worse. In other words, I’ve always understood comics as reflective of the larger world.

“I’m happy that I learned to read reading Mafalda,” Liniers said. “What the strip is basically doing is telling kids, keep asking questions. She’s constantly questioning everything. And when I read it to my kids, I want them to feel that. I want them to read books that will generate that. And you’re going to get a more annoying teenager, but then a more decent grownup.”

“Keep questioning, what’s the deal with this type of politics or that religion. Just question it,” Liniers said. “And whatever doesn’t hold, you can let it go. I love that Mafalda gave that to me.”