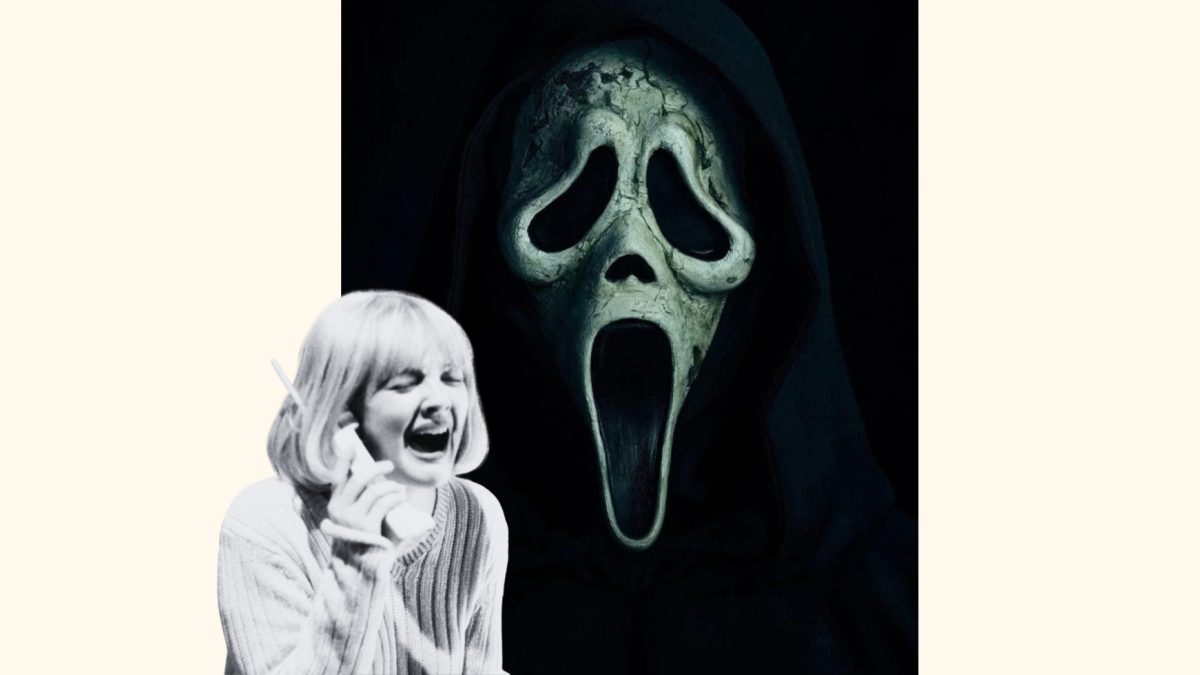

The phone rings. A pretty blond teen answers to find a charming stranger chatting her up on the other end of the line while she’s home alone and making popcorn in her kitchen. What starts as a flirty exchange quickly becomes a living nightmare for Casey Becker. It’s a breathless thirteen‑minute scene that ends with our teenage heroine’s bloody corpse hanging from a tree while her devastated parents scream in anguish.

Article continues after advertisement

The opening of Scream is an entire three‑act story, and Drew Barrymore’s shoot felt, in many ways, like a separate movie all its own. It was filmed in just one week, before much of the other cast had even arrived on location in Santa Rosa.

The scene feels real because a lot of it was. Barrymore would run around until she hyperventilated before takes, and she absolutely refused to fake tears for the camera.

“I remember not knowing what Wes was saying to her, but watching as the cameras were rolling, as she would shriek and cry and break down and sob,” says Julie Plec, who was Craven’s assistant at the time. “I was like, ‘My God, what is going on in there?’ ”

What was going on, it turns out, is that before shooting, Barrymore and Craven were enacting a plan they’d come up with to make sure she could cry on cue: He’d remind her of a horrible story she’d read in the newspaper about a boy who had set a dog on fire to torture it.

“Every time on the set, if I wanted her to cry, I’d say, ‘The boy has the lighter,’ or something like that, and she’d burst into tears and be just frantic,” Craven recalled in a DVD special feature.

Even though he used such a graphic, emotional tool to pull the best performance out of Barrymore, the actress found him to be “a sweetheart” and said that he made her feel “incredibly safe.” The ability to challenge actors while also protecting them, and the empathy that requires, is one of the reasons that Craven is so admired both as a director and as a person.

He was also patient. Scream was Kevin Williamson’s first time on a movie set. He was thrilled to be there, excited by the process, and asking Craven a million questions. “I remember the first day of shooting, standing there in the cold, freezing outside of the house where Drew Barrymore was picking up the phone,” Williamson says. “I remember Wes taking the time to sit down and explain to me not just his shot list but why he was shooting these shots this way and what his plan was for shooting the entire opening scene. That was when I realized, ‘Oh, I put it on the page and he turns it into a real, breathing thing.”

Scream’s first director of photography, Mark Irwin, says they slowly transitioned from a light, nonthreatening palette—blond girl, pastel clothing, mostly white house— to something darker and more dangerous.

“I had to start neutral so everyone buys into this girl with the Jiffy Pop and the flirty stuff,” Irwin says. “The plan in my mind was to change the character of this white, comfortable place. You think you’re safe inside if you lock the doors, and then somebody is pounding on the windows and you realize, ‘I’m not safe in here.’ ”

As the scene progresses, things slowly get darker. They created shadows and moonlight, so the visual mood changes along with Casey’s as she realizes there’s no way to win the game that she’s been unexpectedly and unwillingly pulled into.

“She sneaks outside, there’s shadows everywhere, and we really started cooking,” Irwin says. “There is a frame for lighting called a cucoloris, which is a floral pattern that will create shadows. We had a special one for Drew. She could stop and lean and look over, and all this dapple would heighten the tension, the sense of danger.

“Then she starts running in her bare feet, and she runs around this corner and Ghostface comes out of nowhere and stabs her in the chest. You want to build to that, so the audience is now on her journey and they’re inside her trauma, her vulnerability.”

“They kept me away from [the rest of the actors] so they would not have a face to associate with the voice. The scariest monsters are the ones you make in your own mind.”

It all ends with Casey unmasking her killer before she’s dragged away, still grasping the phone and weakly saying “Mom” as her distraught parents listen from inside the smoke‑filled house. You can feel their hearts break as they discover what happened to their daughter.

“Wes was keen on the deaths being as emotional as possible,” says Scream special effects artist Greg Nicotero. “The audience will identify with the person who is cowering in fear or screaming, and if you relate to them in the last moment of their life, then it’s going to have an impact on you.”

Casey Becker’s death was also visually stunning, which made it immensely disturbing.

Nicotero says it took about five weeks to create her corpse for the “aftermath” shot, from having Barrymore come in to make a cast of her head to sculpting and painting and adding details. It’s a lot of buildup for just a few seconds of screen time, but the work pays off.

“That is classic genre storytelling where you want to unsettle the audience members so that, from that point on, they don’t trust you,” Nicotero says. “You’re on edge because you don’t know what to expect, and the buildup to it is almost as unbearable as actually seeing it in person. Wes crafted that perfectly when he did the opening of all the movies. They had that same visceral gut punch that disarmed the audience.”

One of Craven’s most ingenious moves was making sure Roger L. Jackson, the voice of Ghostface, remained a mystery to the rest of the cast. Having an actor play the lines instead of a crewmember reading them off‑camera was Barrymore’s idea.

“They kept me away from [the rest of the actors] so they would not have a face to associate with the voice. The scariest monsters are the ones you make in your own mind,” Jackson says. “That started the then‑tradition of having me live, on the set, playing the scene with the actors instead of just dubbing later. I could interact with them, so it became my job to scare actors—a job I enjoy very much.” (Jackson went into the voice on those last few words, and despite being able to see on Zoom that it was him and not Ghostface, it was chilling. So, for the record, I think he’d still be able to scare the actors even if they’d already met him.)

“That voice is remarkable,” Neve Campbell says. “It’s set in our minds now. If any of us hear that voice, we know what it is and what movie it’s from—and it gets me every time I hear it. The resonance of it, and he’s so vicious. It’s wonderful. It’s a lot of fun.”

The first night, Jackson was under a canopy outside looking in through the window. The second night, they moved him into the garage and set up a camera feed. Later in the shoot, at Sidney’s house, they hid him in a walk‑in closet.

When a movie catches you by surprise the way the opening sequence of Scream does, it leaves a mark. It’s also the scene that almost got Wes Craven fired just a week into filming.

“I felt bad for him, ya know, because we had to keep waiting till everyone was on set and then sneak him somewhere,” assistant director Nick Mastandrea says. “But he was good‑natured about it all.”

“Drew was phenomenal in that sequence,” Williamson says. “She memorized it to a T. She got every scream, ‘No, no, no, aah!’ She had it all down pat. She was such a professional. She was so prepared and she just committed. Her performance set the stage for what was to come.”

There’s a reason Scream’s opening is iconic. It’s at once clever, chilling, and heartbreaking, the kind of unforgettable storytelling that can make something as routine as turning on patio lights at night give you pause decades after watching it. Sure, it’s unlikely that there’s a disemboweled high school football player strapped to a chair just steps outside your back door, but you may still find yourself nervous as you’re flipping that switch. Because when a movie catches you by surprise the way the opening sequence of Scream does, it leaves a mark.

It’s also the scene that almost got Wes Craven fired just a week into filming.

The cast and crew on the ground in wine country that first week saw Craven’s vision come to life and knew they were making something special. Dimension Films head Bob Weinstein, however, was utterly unimpressed based on what he was seeing in the dailies, raw footage shot dur‑ ing any given day of filming that helps the studio keep tabs on a project from afar.

One day while sitting in the parking lot of the grocery store where they filmed the shopping scene with Sidney and Tatum and the news footage clip of Cotton Weary get‑ ting into a police car, Craven got a scary call himself.

“I just watched his shoulders slump in his director’s chair when he got the phone call from Bob saying he hated the dailies,” Williamson remembers. “It was devastating that day. It just broke all of our spirits.”

Cathy Konrad had made several movies with the Wein‑ steins and she braced herself for the worst. “I was the only one that knew to the depth of my soul what could happen when the train comes off the track,” Konrad says.

Executive producer Marianne Maddalena remembers that Weinstein told Craven his shooting was “workmanlike at best” and complained that it was “just a girl running around with a telephone in her hand.”

Dimension executive Richard Potter says there was a disconnect between what Weinstein was seeing in the raw footage and what he had been expecting. “When Wes shoots, he is shooting for Patrick to edit. Patrick knows in a forty‑second shot that there’s twelve seconds three‑quarters of the way through that Wes wanted. That’s what he was going for,” Potter says. “When Bob watched the dailies, he thought it looked boring. It didn’t look like anything was happening, and he was kinda freaking out that the movie wasn’t going to be good.”

“Wes built it in his brain as he was shooting it,” Konrad says. “He knew the building blocks he needed to create the tension and to give the audience what they want. That’s a gift. A lot of people have a hard time looking at rough material and imagining it to be something.”

Craven and his team knew they were on the right track, but hearing someone say he was phoning it in was hurtful. “Wes was a very sensitive man, a very sensitive artist,” says Julie Plec. “And that was really, really, really heartbreaking for him to hear.”

Much of the issue came down to the now‑iconic Ghostface mask, which Weinstein hated.

In retrospect, it’s hard to believe there was ever a doubt. As actor Jamie Kennedy puts it: “Ghostface is like Mickey Mouse. That sounds weird, but they’re that recognizable.” President of the studio Cary Granat flew out to Santa Rosa from New York to deal with the situation—which he says has “grown into its own mythos” over the years—and to talk to Craven about the mask and the direction of the movie.

A lot of drama, a lot of emotion, a lot of anger, a lot of chaos, but at the end of it all also a lot of support.

“The first meeting was very tough because Marianne and Cathy were, rightfully so, protecting Wes and being very ardent that everything is fine,” Granat says. “That first meeting was very heated and didn’t really go anywhere.”

That’s one way to put it.

Plec’s description is a little more colorful: “Cathy said, ‘If you don’t like it, then shut us down or fuck off.’ Something to that effect.”

“Yeah, I did. I said that to Cary Granat,” Konrad recalls. “He wanted me to help him talk to Wes and have the cast shoot the same scenes, multiple versions, with different masks to show Bob and have him pick. It was so audacious, the request.”

There was pent‑up frustration simmering because of her experience on past movies with Miramax when during the Scream shoot she got a late‑night call from a man asking, “Do you like scary movies?” At first she thought it was a prank, and she wasn’t in the mood.

“It was Wes inviting me to the room to hash this out with Cary,” Konrad says about the tense meeting with Granat. “I was so mad. Yeah, I said, ‘Shut us down or fuck off,’ basically.”

He did neither. Instead, Craven and crew came up with a plan: Lussier would cut the entire opening scene so Weinstein could see that everything was going exactly as it should.

“I don’t remember whose idea it was, but I’m sure nine people will take credit for it,” Plec laughs.

Lussier had edited Wes Craven’s New Nightmare and Vampire in Brooklyn, so Craven knew he’d be able to turn it around quickly. “I had a reputation for being able to cut fast, but I would also cut things with music and sound effects so they looked like a finished movie,” Lussier says. “I would send tapes to set, back when you sent VHS tapes of the cut scenes, and Wes wouldn’t even watch them first. He would just show them to the crew.”

So, even though it was out of the ordinary, it was a pretty safe move. Craven’s only note when he saw Lussier’s cut was to make a bigger orchestral crescendo for the very last moment when you see Casey Becker disemboweled and hanging from a tree.

“He was confident that he could win them if they saw it cut together, and he was right,” Lussier says. “It very clearly worked. It was an empirical thing. It wasn’t a subjective thing. It wasn’t like a fan blowing across the desert and it depends on what your mood is when you watch it. It was a really visceral, gut‑wrenching thirteen‑minute experience and it was a complete story.”

Potter arranged for Dimension trio Bob Weinstein, Cary Granat, and Andrew Rona to fly to Santa Rosa and watch the cut‑together scene. He hadn’t seen it himself at this point, so he was a little worried that it would be a disaster and Weinstein would tell him to “fuck off,” fire him, and shut the whole thing down. To everyone’s relief, it went the other way. “They saw the scene cut together and it was exactly what everyone was hoping it would be,” Potter says. “And it is a hundred percent true that Bob went up to Wes and said, ‘What do I know about dailies?’ ”

“They backed way off and let him just make the movie,” Lussier says. “Suddenly, there was money for everything. There was money for an orchestra. All that changed because of that thirteen and a half minutes. My whole career has changed because of that sequence.”

“It was brilliantly done by Wes, and from that moment on there was tremendous trust with Wes in terms of what he needed moving forward,” says Granat. “As difficult and painful as it was, it was the right thing to do at that moment. If that summit, so to speak, didn’t happen, there would have been a lot more frustration and pain throughout the entire shooting process. I think it would have affected the outcome of the film. The fact that it was nipped in the bud so early enabled the shoot to just move forward and let them push the envelope as strongly as they could.” “It was a fraught relationship,” Plec says, “as is the case with most movies that were made by those guys. A lot of drama, a lot of emotion, a lot of anger, a lot of chaos, but at the end of it all also a lot of support. They paid for the movies, they marketed the shit out of the movies, and they made them hits.”

Years later, Craven used the experience as a cautionary tale when asked what advice he had for young filmmakers. “Don’t trust anybody and persevere, really, really persevere. Don’t trust anybody’s judgment about what will work except your own,” Craven said. “If you don’t have that knowledge inside of yourself of what’s going to work for you when you’re making a film, you probably shouldn’t be doing it. But if you have the drive and you have the talent, then don’t let somebody talk you out of it.”

Without naming Weinstein, he recounted how a studio exec told him his camerawork was boring and suggested he watch another filmmaker’s work. He didn’t watch it, by the way.

“The Drew Barrymore sequence became kind of a classic,” Craven said. “You have to be very, very careful about guarding yourself against being influenced by other people who will act like they know exactly what they’re talking about and more than you do. So, just follow your inner vision and really stick to it.”

_________________________

Excerpted from Your Favorite Scary Movie: How the Scream Films Rewrote the Rules of Horror by Ashley Cullins. Used with permission of the publisher, Plume. Copyright 2025 by Ashley Cullins.