The first time I met Austin Clarke—in the mid-1980s at his house on McGill Street in Toronto—he gave me two things.

Article continues after advertisement

One was an old paper copy of the duplicate galleys for the last novel in the Toronto Trilogy, which bore an early version of the title—To Name the Bigger Light—shortened, of course, to The Bigger Light when it was published in 1975. Printed on eight-and-a-half-by-twenty-inch paper with extra-wide margins for notes by editors, proofreaders, and Clarke himself, the manuscript appeared especially thick when he gave it to me because it was folded in two. It was stained in several places, disintegrating around the edges, and already yellowing due to years of exposure to air and sunlight and, quite possibly, pipe tobacco. Throughout the manuscript, Clarke had made minor handwritten corrections in an early version of what would become his ubiquitous writing style, one Paul Barrett, in his article “On Austin Clarke’s Style,” calls “calligraphic works of art.”

The other thing Austin gave me was a photo of himself. I was getting ready to head back to the University of Waterloo, where I was in the first year of an undergraduate degree in English language and literature. We had spent a rather awkward and tentative couple of hours together in the living room at the front of the house, where Austin served tea very ceremoniously in his “good good china.” Then he mused aloud about the relative mediocrity of my choice of university, much preferring, he said, the top-rated American colleges he had sent his two daughters to.

We both ignored his slip of the tongue.

As I stood at the opened front door, Austin handed me the bag he’d put the manuscript into, along with a large nine-by-twelve-inch envelope that contained the picture he’d rummaged through his desk to find. I stuffed them into my backpack and rushed out the door and down the front steps to catch a streetcar to Union Station. I looked back once and saw Austin standing on the porch, his left hand on his hip, his right hand extended out from his body, resting on the column that supported the porch roof. That stance is one of Austin’s ubiquitous attitudes. I recognize it in photos of him taken by his friend Abdi Osman, an artist whose work grapples with representations of Black masculinity.

The hastily scribbled note in the corner of the photograph recalls an exchange I had forgotten, marks the moment, and situates me and Austin in the time and space of that first encounter.

On the train, I opened the envelope and pulled out the photo Austin had given me. It was a black-and-white headshot taken—I learned much later—by the renowned Canadian portrait photographer John Reeves in his studio at 11 Yorkville Avenue. The photo is undated and stamped in ink that is almost completely faded, but Reeves’s name and the studio address and phone number are still visible on the back. Sitting at a slight angle and dressed formally in shirt and tie with a classic houndstooth tweed jacket, Austin stares directly at the camera through half-wire-rimmed glasses. His intense gaze inverts the relationship between the subject and the viewer, conveying the sense that he is in full control of what the viewer sees.

In the space to the left of his head, he wrote:

For my daughter, Darcy,

who doesn’t like beards!

With love,

Dad

I don’t remember telling Austin that day that I didn’t like beards, which is not true. The only explanation I can think of to account for the comment is that I must have expressed surprise when the man I encountered—formal, impeccably well-mannered, reserved—did not match the image of Austin Clarke I had inherited. In family narratives, he was invariably cast as the villain in the domestic drama that gripped my extended family when my young white biological mother became pregnant out of wedlock with an older Black man from “the big city” who was firmly in wedlock and father to two young girls.

I’m not sure what else we talked about in the couple of hours we spent together that day—other than facial hair and my failed choice of university. But the hastily scribbled note in the corner of the photograph recalls an exchange I had forgotten, marks the moment, and situates me and Austin in the time and space of that first encounter.

The manuscript and photo took up space in a box with other ephemera I carted with me as I moved into and out of various apartments during my B.A. and M.A. and over many years when I worked in the public sector in Ottawa, Quebec City, Vancouver, and Montreal.

Two decades passed before I saw or heard from Austin again.

*

The second time I met Austin Clarke was in the early 2000s, after I’d moved to Toronto to do a Ph.D. We met in the lounge at the Grand Hotel on Jarvis Street (a place I became familiar with while he was alive), where Austin often dined, socialized with friends, mentored young writers, or sat alone with a martini—or several martinis—after a long day of writing, jotting down ideas for new stories on hotel letterhead.

In the ensuing years, until his death in 2016, he regularly gave me scraps of paper and other odds and ends; at the time, I had no code or context with which to decipher them. I kept them simply because he had given them to me. I first dismissed (and almost discarded) this arbitrarily marked-up paper, but it charts Austin’s trajectory across the city he loved—via the many hotel lounges, clubs, and bars where he sat thinking or working on story ideas—and reveals his rigorous daily writing practice. The methodology tells its own story about the writer crafting the story.

Over the course of our too-short father-daughter relationship, Austin also gave me ten or so small diaries, in which he kept track of the kinds of things one would expect, such as addresses, important dates, and outings with friends. But the diaries also reveal Austin’s wicked and often dark sense of humor (a scribbled note to the right of a column of cricket scores says Jamaican cricketer [Chris] Gayle is a stupid bastard!). His entries on financial matters speak to how Austin wielded that humor in navigating the world. On one page he writes “First pay day—broke day after”; on another, a list of tasks he promises to undertake to become “a millionaire.”

Austin’s critiques of the difficult process of setting up a Black studies program at Yale, which he mentions frequently across the diaries, incontrovertibly situate him and his contributions in founding Black studies in ways that cannot be denied or glossed over. One entry reads, in an oft-used uppercase script: Black studies irredeemably disorganized & muddled—from secretary to director. May leave at end of term. Hopeless situation, and another short note reads: Yale Black faculty met—useless meeting. Given that he was a visiting lecturer, not tenured faculty, Austin’s commitment to formalizing Black studies at Yale is remarkable. He would eventually leave New Haven when his contract expired, returning to Toronto and his first love, writing fiction.

*

Austin was fond of telling me that my grandmother, in particular, and the rest of his family—my family—were eager to meet me and that he would take me to New York “soon, soon.” We finally made that trip in winter 2005, the year his mother, Gladys Luke, died and he took me to her funeral, where I met his siblings, cousins, nieces, nephews, and other family members and close friends. The encounter was overwhelming for all the reasons one would expect, but it was made more so because, as I discovered a few hours after our arrival, Austin had never told them about me—perhaps because of long-held customs around remaining silent about “outside” children. Until I clarified things, they had assumed I was his girlfriend.

I am struck by the note’s simplicity and brevity in relation to the crushing, complex, and ongoing weight of illegitimacy, exile, racism, and abandonment that it foreshadowed.

When I look back on those moments of revelation in his sister Anna’s crowded living room, I think Austin was creating—or maybe witnessing the unfolding of—a story he had plotted. I can picture him sitting on the sofa quietly observing the proceedings and listening intently to his family’s reaction to the news of our actual connection. There was a kind of trickster’s glee in his expression. I also think Austin wanted his family’s tacit approval of me before he would allow himself to completely embrace his “newly discovered” daughter—the outside, illegitimate child who resembles him in so many ways.

After his death in 2016, I became more attentive to the odds and ends Austin had tucked into used envelopes and passed to me over dinners out or drinks at his favorite haunts. Now, when I see my name written in his hand in some of the later diaries or his expression of contentment in a picture of the two of us taken at an event we both attended, I recognize that the small gifts he gave me were his way of communicating feelings and thoughts he was never able to articulate in the small window of time we shared before he died. We never had a sustained serious or significant conversation.

We didn’t talk about writing or academic life. We certainly didn’t talk about the past or my upbringing or my mother or whether he was aware of my existence before I reached out to him when I was in my early twenties. I wasn’t ready then to engage with Austin the man and father in the ways I do now as a Black studies scholar, researching and writing about his work in the wake of his death, arranging the tracery of what he left behind. When I consider my personal archive of notes, accounts, lists, reminders, and jottings, I often think his true form is the note scribbled on a scrap of paper or a napkin, in a diary, or in the margins of a book.

*

The house we moved to when I was still in grade school, in a rural Ontario farming community, was flattened by a category F4 tornado in 1983, its contents scattered across the ruined landscape. Years later, someone who knew me—I don’t recall who it was—gave me a weathered copy of George Lamming’s novel Of Age and Innocence that had been recovered from the debris. I wasn’t familiar with Lamming’s writing at the time and didn’t understand why I’d been given the book. So I was stunned when I opened the front cover and read the note that was written on the flyleaf in December 1962, nine months before I was born:

To Mother, wishing you many hours of pleasant reading. And with the hope that this will be just one of the many delightful books about my people, written by a West Indian. Austin

Xmas 1962

The book was a gift Austin had given to the woman who was his host during the Christmas holidays in Sarnia that year. The note written on the flyleaf eerily predicts the future of the host, who would become my maternal grandmother and, six years after I was born, my legal adoptive mother. Likewise, it anticipates the texture of my biological mother’s life. She was banished from her family home (the one I eventually grew up in) to wait out her pregnancy and give birth to her child alone. Her presence haunts the note, but she is not named or invoked in it. In the years since my birth, she has been mostly absent too; her name spoken only occasionally and almost always in relation to the family secret or conjecture about what really happened all those years ago.

I am struck by the note’s simplicity and brevity in relation to the crushing, complex, and ongoing weight of illegitimacy, exile, racism, and abandonment that it foreshadowed. When I read Austin’s brief note now, I can’t help but see how we are all contained in and by it. Each of us unaware of the complicated future awaiting us as we grew into the shape of the characters he drew in this small narrative.

__________________________________

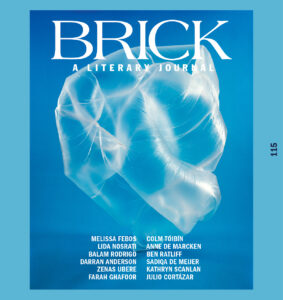

“‘With Love, Dad’: Imagining Austin Clarke” by Darcy Ballantyne appears in the latest issue of Brick Magazine.