Growing up, I never imagined that I would become a wildland firefighter, or any firefighter for that matter. I grew up in the eighties and nineties, when there were very few firefighters, wildland or otherwise, who weren’t men. My single mom was a secretary. We moved often, sometimes over twice a year, and although I intermittently played basketball at the Boys & Girl’s Club, athletics were much less attractive to me than reading and listening to music. I wasn’t competitive by nature. In high school I was kicked off the volleyball team for smoking cigarettes. The only sports I enjoyed were swimming and exploring the small swaths of wildland that sometimes surrounded our apartments, or my grandparents’ house in the Seattle suburbs.

Article continues after advertisement

None of this, including my solitary life as an only child, pointed to firefighting as a profession.

I was nineteen when I began fighting fires. By then, I had been a tween and teenage runaway, a sex worker, and a survivor of violence inflicted by both strangers and people I knew, most notably my mother. Anyone eyeing my life trajectory would have guessed that I’d end up permanently homeless and possibly addicted to several substances. That did happen. That’s the life wildland firefighting saved me from.

White and purple crocuses were barely puncturing the soggy ground when my friend Kelly suggested I try wildland firefighting. It was the year 2000 and I was living in Eugene, Oregon, attending community college a few hundred miles south from where my mom and stepdad lived in Olympia, Washington. The world had survived Y2K but winter had tested my will to live—first my grandmother, my soul mate whose first name I shared and with whom I’d lived intermittently as a child, had died. My mother warred with her siblings over their respective inheritances; my grandfather moved into a sad little apartment, where he fell and sustained a head injury, resulting in memory loss.

My life unraveled.

Organization, calendars, homework, and mundane tasks had always been difficult for me, and I was constantly at war with myself over these inadequacies. Bulimia was my primary coping mechanism, along with drinking, drugs, and sex. A few weeks into my first spring quarter I stopped attending classes, telling no one. Short gray days and long nights only accelerated my sense of disconnection.

For a while I worked as a hotel housekeeper, until too many no-shows got me fired. Then I worked fast food, cycling through McDonald’s, Taco Time, and random mid-level indie eateries. After exhausting all opportunities for steady employment, I relied on the local Labor Ready for my paychecks, which mostly went to rent, alcohol, and drugs.

But we weren’t there to admire the forest. We were there to grid.

Kelly, along with her roommate Peter, was one of the few people who knew all of this, and the debilitating depression underneath. She was also an experienced former wildland firefighter. “It will distract you,” she said, flipping through a photo album filled with pictures of herself from when she had worked on the crews several years ago. In them she looked happy, grinning in her orange hard hat. She must have expected me to say no, because she reminded me that I was already doing manual labor, lifting heavy things and surrounded by male co-workers, many of them older, in dire straits of their own. I didn’t need much convincing. I would have tried anything.

A week later I was hired. Two weeks after that I was on my way to New Mexico for my first fire assignment: The Viveash Fire. By 2010, when I left firefighting, I had worked two years on Type 2 contract crews, four as a hotshot, and one year as a helicopter crew member. Type 2 crews commonly clean up after a fire has burned through an area, whereas hotshot crews are classified as Type 1 crews and conduct initial attack, usually working in direct contact with active fires. Hotshots are elite firefighters with a more complex skillset than Type 2 crews, though they’re often called “unskilled laborers.”

Now I have my own album of fire relics, including a faded newspaper clipping about a famous actor’s ranch house at risk of burning, along with a dirty Incident Action Plan (IAP) my first crew boss gave me for a keepsake.

I discovered a whole world of wildland firefighting—an entire subculture of mostly men who spend their summers crisscrossing the United States fighting forest fires, desert fires, grassland fires, palmetto fires. All kinds of fires, many of them in areas rarely traversed by humans. And I became part of it when we pulled up to the Viveash fire camp in the government-issued yellow school bus. Rolling into a fire camp for the first time is a bizarre experience for anyone who’s had the privilege of never enduring a catastrophic disaster. It summons images of military outposts and refugee camps, but we were merely a ragtag group of misfits hoping to cash in on some overtime pay.

Out of the twenty-one of us, seventeen had never once been on a fire assignment. We marveled at the bustling outpost, with its canvas tents for incident command, staff, logistical personnel, a first aid tent and field medics, a canteen, fresh gear and tools, showers, port-a-potties, fields of small multicolored camping tents, and a kitchen trailer large enough for a decent salad bar. The horizon, lined with ragged, sand-colored peaks, hinted at the mountainous terrain where the fire burned.

Sophisticated fire camps aren’t erected until a fire is large enough to require more than a handful of resources. Fire sizes are rated according to the Incident Command System, with Type 5 fires being the smallest and Type 1 being the largest and most complex. This system isn’t exclusive to wildfire response but applies to any large-scale emergency, including hurricanes, earthquakes, and pandemics.

Type 4 or Type 5 incident management teams consist of no more than ten people local to the area, maybe city or county fire along with a federal resource, depending on land jurisdiction. Someone assumes the role of incident commander. Many fires ignite and are extinguished without the need for an official fire camp, but if a fire grows in size the incident commander orders more resources, like fire crews, aircraft, and engines, and a fire camp is erected to sustain those resources.

The Viveash was a Type 1 incident. There were more than one thousand firefighters and personnel assigned. One of several large fires burning throughout the southwest, the Viveash was ignited by lightning, a common spring occurrence in the southwestern United States. The lightning storms are often accompanied or shortly followed by monsoons, but this year the monsoons were late. 2000 was a drought year and forests were parched and overgrown.

A few weeks earlier, the National Park Service had lost control of a prescribed burn in Bandelier National Monument, sixty miles east of us. The resulting fire, named Cerro Grande, exploded, threatening the town of Los Alamos and destroying a handful of buildings at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Agencies rarely lose control of prescribed fires but the media pounced, as they always do, capitalizing on the public’s understandable fear of fire.

Despite burning through sparsely populated land the Viveash garnered an outsized response because it followed the Cerro Grande fire. It’s a familiar cycle to me now—the way media attention dictates federal fire response—but I didn’t think twice about it back then. We set up camp, nestled amongst several other Type 2 contract crews (confusingly, a separate system from the numbering of fire size), and I was supplied with a canvas pup tent and two sleeping bags along with some wool blankets to sleep on.

[/pullquote]“I want to do that,” I said. He shook his head, looking almost sorry for me. “You can’t be a hotshot. You’re a girl.”[/pullquote]

My first two weeks are imprinted in my mind because everything was brand-new. Each morning we rode the bus for over an hour, ascending a treacherous pockmarked ancient dirt logging road. Seatbeltless, we were jostled and bounced, sometimes raising our hands to stop ourselves from hitting the metal ceiling. We emerged sleepy-eyed from the bus, grabbing our packs from the open back door, breathing in exhaust from the tailpipe. The land around us was completely scorched; I’d seen nothing like it before. Bare, blackened trees with pointed, spindly limbs and black soil that felt strange underfoot, both spongy and brittle. The air smelled sweet and repellent, like a puttering campfire. Each footstep sent up clouds of dust and ash, coating everything, including my mouth and teeth, in fine grit, blackening my snot and saliva.

Like all fires, the Viveash was parceled into divisions named using the NATO phonetic alphabet, from Alpha to Zebra. Some of it was bare as a moonscape, some was burned in a mosaic pattern, with patchy green and brown tufts of grass and baby pine trees with newly browned needles. The high-altitude aspen groves, naturally fire-resistant, stood out like shining islands carpeted in tall emerald grass, some of it tinged black. The bright white trees, their trunks lined with deep gray and black markings, were juxtaposed with patches of scorched earth, creating a surreal, discordant kind of beauty I’d never seen before, except in works of art. But we weren’t there to admire the forest. We were there to grid.

Imagine a search and rescue team searching a forest for a missing person: They line up ten or fifteen feet apart from each other, pausing at any hint of evidence and moving at a crawling pace so they don’t miss any clues. Mopping-up is like that. The searching is called “gridding,” for its grid formation, each person or team responsible for searching square by square. Instead of clues left by a person, we looked for any residual heat, like smoldering roots or wisps of smoke arising from stumps and logs.

We walked, and walked, and walked. Every day. For twelve hours a day. It was mind-numbing. I hid my watch in my pack because checking the passing time was torturous. Still, the job was good. I liked being away from civilization, where I couldn’t get into trouble. There was no booze and no drugs. All those decisions in the outside world—I didn’t need to make them anymore. Every night I fell asleep right away, and every morning we woke up at the same time to our crew boss George’s gruff voice or the sound of a crew member’s singing. My life had never been so stable.

One afternoon, George’s radio flared with chatter of medics and heat exhaustion. Two hotshots were being flown by helicopter to the local hospital. I’d almost forgotten there was an active fire—on our divisions, where we’d been assigned to work, the air was mostly clear, and any noise of aircraft was far away. I thought of the hotshots working closer to the flames. A few days earlier I had seen my first hotshot crew. They pulled into camp, supposedly to shower, and emerged from their buggies while we were at chow. They descended and devoured. Their yellow Nomex shirts were black, brown, and striped with mysterious ghostly lines I would later recognize as sweat stains. Their faces, covered in grime, were nearly indistinguishable from one another. They were quiet, almost silent, as they ate. Big guys. Solid, strong guys with militaristic countenances. I watched my crew boss watch them, as many others at the chow tent watched them, with reverence. Then they left. When I asked George if those men were hotshots, he nodded. “I want to do that,” I said. He shook his head, looking almost sorry for me. “You can’t be a hotshot. You’re a girl.”

Wildland fire crews, and hotshots in particular, wouldn’t exist as they are today without the New Deal, which was enacted in 1933 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as an effort to counteract the Great Depression. The United States Forest Service (USFS) and National Park Service (NPS) were still young and underfunded; twenty-eight and sixteen years old, respectively. Both held jurisdiction over millions of public land-acres and neither agency had enough funding to keep pace with increasingly strict fire suppression policies.

President Roosevelt wanted to reignite the country’s passion for conservation while creating jobs for unemployed men who couldn’t support their families. He created the Civilian Conservation Corps and erected segregated work camps, over two thousand of them over nine years. Hundreds of thousands of (mostly white) men planted trees, cut firebreaks around townships, built bridges, created state parks, and fought forest and brush fires. Non-white men had less opportunity to work. Much of the fire infrastructure that exists today was built during the New Deal, including fire lookouts and thousands of miles of firebreaks, many of which have been ill-maintained due to continued lack of funding.

Wildland firefighters define a good season as one that the public calls catastrophic.

By the mid-forties, cohesive fire crews began taking shape. One thirty-man crew in the town of San Bernardino, located in Southern California, specialized in initial attack. In 1946 they began calling themselves the Del Rosa Hot Shots. Two years later, the Los Padres Hotshots were established about two hundred miles north, near Santa Barbara. It makes sense that hotshots were born in Southern California, where the fire landscape collided with several population booms and set off what’s now known as the light burning debate—an ongoing argument for and against full fire suppression.

Today, hotshots, also known as Type 1 fire crews, or Interagency Hotshot Crews (IHC), are federal entities under the banner of three agencies: the United States Forest Service, National Park Service, and Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Each separate agency has a unique purpose, but they are all inextricably connected. The BLM (created in 1946) is the youngest of the three agencies and primarily manages rangelands. Their trademark triangular signs are ubiquitous in arid regions of the United States, like the Great Basin. The NPS (formed in 1916) is the second youngest of the three, behind the USFS (1905). The Forest Service has the most firefighting resources, including hotshot crews. There are thirteen BLM hotshot crews. The Park Service has only two: one in Sequoia National Park and the other in Rocky Mountain National Park, in Colorado. Comparatively, the USFS has over a hundred hotshot crews under its jurisdiction, a reflection of its massive fire suppression funding and aims. Seven hotshot crews operate under the umbrella of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and individual tribes, as well.

Most people have no clue what a hotshot is, but in the wildland fire community hotshots are held in high regard. Hotshotting is complex work. The requirements and safety standards are stringent. Crews must have, at minimum, eighteen people at all times. Because of the frequency of injury and job abandonment, most crews start each fire season with 22 people and end it with 18 or 19. Not only is the work physically and mentally grueling, hotshots must dedicate at least six months of their life to their crew, sacrificing time with family and friends, along with individual autonomy. For most, it’s a summer job lasting a season or two. For some, it’s an entire career.

Despite these demands, and despite the colloquial title of elite firefighter, hotshots weren’t officially categorized as firefighters until the summer of 2022. Before then, the federal government called all wildland firefighters forestry technicians and denied them the benefits typically granted to nonfederal firefighters, like health insurance and retirement, as well as “portal-to-portal” pay, which keeps firefighters on the clock for as long as they’re away from home base. There was no health insurance offered when I was a seasonal hotshot—all we had was worker’s compensation, in case we got injured. Seasonal wildland firefighters are now offered temporary health insurance.

My pay as a GS-2 (the second-lowest rank of government worker) was under $12 an hour in 2002. In over two decades, that rate has budged by barely three dollars an hour. In California, I got a cost of living stipend, and if we were working on “uncontained” fires an extra three dollars (called “hazard pay”) was tacked on to our hourly wage. For this reason, the gold standard for a “good” fire season is judged by how many hours of overtime are accrued throughout the season. If it’s a slow season, a hotshot, the most elite of wildland firefighters other than smokejumpers (who jump out of planes into small, remote areas unreachable by vehicle), can make as little as seventeen thousand dollars for six months of work.

Wildland firefighters define a good season as one that the public calls catastrophic. They don’t make a living wage without catastrophe, but either way they sacrifice their summers, remaining within the required two-hour radius of their base, so they can respond quickly to fire calls. Federal hotshot crew members and wildland firefighters get paid, on average, about 33 percent less than wildland firefighters who work for state agencies.

In 2023, a nonprofit advocacy group called Grassroots Wildland Firefighters worked with Arizona Senator Kyrsten Sinema and other federal legislators to introduce the Wildland Firefighter Paycheck Protection Act, which temporarily increased benefits and raised pay for nonseasonal (permanent) wildland firefighters by up to 42 percent while also increasing hourly pay for seasonal workers by two dollars an hour. While this is a solid first step, it’s still not permanent as of this writing.

There are many ways to reflect on the United States before and after colonization, but few people do so exclusively in terms of fire.

Seasonal federal wildland firefighters still lack many benefits and protections, like subsidized comprehensive health insurance. Their base pay is now $15 an hour, which is the minimum wage in many states and cities. Because of low pay rates, wildland firefighters want overtime, but too much overtime raises their risk of injury and exhaustion and extends time away from family, friends, and important social networks, often leading to a sense of disconnection from one’s community and a jarring reintroduction when the fire season ends. Suicide rates amongst wildland firefighters are high, and likely underreported.

In 2018, a survey found that 55 percent of wildland firefighters have exhibited suicidal behavior or ideation, compared to 33 percent of non-wildland firefighters, but consistent and reliable data regarding the mental health of wildland firefighters simply does not exist. Federal wildland firefighters sacrifice their summers and risk their lives for low pay because they love the job—this is true for most federal employees, many of whom could easily find work that not only offers more balance, but pays better, too.

I came into firefighting by happenstance. Like my peers, I also wished for more fires and overtime despite the accompanying exhaustion and pain. Had I not left the profession in 2010, I would have eventually gotten my wish—since 2005 wildfire occurrences throughout the United States have doubled, and fires in the western United States have at least doubled in size, on average. Large fires are burning longer and fire behavior is increasingly unpredictable. The National Interagency Fire Center has reported that the ten largest fires since 1980 burned after 2003. In the twenty-four fire seasons since 2000, twelve burned over eight million acres.

The cost of suppression has also risen: Agencies have spent over one billion dollars each season for all except four years since 2000, with five of those twenty-one years costing over three billion dollars. This isn’t only a western occurrence. In late autumn of 2024, historical fires burned throughout the Northeast, incited by record-breaking drought.

Then, in January 2025, several fires ignited in Los Angeles. Spurred by the Santa Ana winds, the fires destroyed over 17,000 structures, many of them in the historically Black and working-class neighborhood of Altadena. January wildfires in Los Angeles are historically quite rare. Media outlets coined the word “megafire” in the 1980s, and scientists picked up the term in 2005. Any fire over one hundred thousand acres is categorized as a megafire, but in 2020, after California’s August Complex fire burned over one million acres, someone in a comment section coined the term “gigafire.” It stuck.

These changes are usually framed in terms of climate change, which has lengthened fire seasons and weakened ecosystems in complex ways. But climate change is only one of many factors in what has become a profound shift in the fire landscape. The shift may appear sudden, but it’s happened gradually. We can trace it back to 1492, when Europeans first began colonizing the United States.

There are many ways to reflect on the United States before and after colonization, but few people do so exclusively in terms of fire. I certainly never considered any connections when I was a hotshot. It wasn’t until I started research for Hotshot, years after I left firefighting, that I thoroughly traced the connections. Many narratives detailing the history of fire suppression in the United States cite the Great Fire of 1910, which burned over three million acres of land in the Northwest, as the beginning of fire suppression. It was a beginning of some sort, but not the beginning, nor was it the first catastrophic fire in the United States. Before the Great Fire of 1910, catastrophic fires followed logging from east to west, and debates surrounding fire suppression were happening well before 1910.

For thousands of years before colonization, both anthropogenic (human-caused) and natural fire were common and vital to nearly all North American landscapes. Europeans brought particular ideas and beliefs surrounding fire, agriculture, and land development, as well as insatiable and destructive appetites for natural resources. Most were oblivious to the sophisticated ways Indigenous people tended their land, including the use of fire as an agricultural tool. Fire was, and is, a sacred and essential part of the lives and cultures of many Indigenous Americans, and Indigenous cultures around the world.

Most ecosystems in North America evolved with the presence of fire on a seasonal cycle. The near-constant presence of smoke is commonly mentioned in the journals, logbooks, and narratives of early North American settlers and explorers. Today, there is extensive scholarship detailing Native American use of fire and early fire ecology—scientific (drawn from soil, tree-ring, and glacier datasets), anthropological, and historical.

One thing that is inescapable is that the impact of colonization on ecological landscapes and Native Americans is both ugly and intimately interconnected with the history of fire suppression in the U.S.

__________________________________

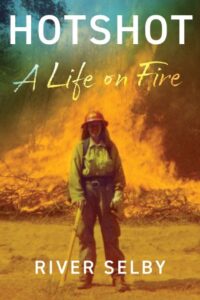

From Hotshot: A Life on Fire. Used with the permission of the publisher, Grove Atlantic. Copyright © 2025 by River Selby.