It’s time to take stock.

Article continues after advertisement

It’s an interesting phrase, that, first attested in 1736 to indicate drawing up an inventory of goods, coming eventually to mean to think carefully about something before deciding what to do next. The related phrase to take stock in, on the other hand, is an expression of confidence, “to regard something as important,” a usage dating from 1870 or so and emanating from the world of financial investment and capital gains.

Both idioms arose because sheep, goats, and cows were once as good as gold—livestock—and in some parts of the world they still are. The Roman antiquarian Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), at any rate, expresses delight that the Latin word for money, pecunia, was derived from pecus (“a flock or herd animal”) and that fines in his day were still levied at the market price of oxen and sheep.

Originally, however, the word stock, of Germanic origin, denoted a stump or stick (Stück), the lifeless mass that’s left behind once you’ve chopped down a tree—deadstock you might say. In recommending that we look again to the past to learn to live in the present and future, following Nature’s lead, I only hope not to have become a laughingstock, a compound derived from this original sense as a useless remainder, worthy only of scorn, a stick in the mud, as it were.

And yet anyone who has cut down a deciduous tree will know that it soon grows back. (Conifers, alas, tend not to.) Hence the idea of coming from good stock, meaning that one’s root system and potential for life is strong and vigorous.

Let’s take stock of the various arguments we’ve collected, consider whether they come from good stock, and whether they’re something we should take stock in.

This bundle of associative meanings and images pretty much sums up my stab at a conclusion here. Let’s take stock of the various arguments we’ve collected, consider whether they come from good stock, and whether they’re something we should take stock in. Are they livestock or deadstock?

There are many potential objections to any argument and, these days, it seems, doubt about what constitutes facts and evidence itself. What is worse, whataboutery, which characterizes so much public discourse, has trickled up, even to Academe.

What about ancient slavery and chauvinism? Didn’t Aristotle argue that slavery was “natural?” Didn’t he think that women were biologically inferior, defective versions of men? Weren’t all the ancient elites whose writings survive ultimately colonizers and oppressors?

Whiggery, too—the idea that humans in the present categorically know better than humans in the past—is another obstacle. Scientifically, the ancients were flat wrong about all sorts of things.

Look no further for proof of our superiority, believers in progress say, than all the conveniences and improvements wrought by the applied science of technology. We risk anachronism and distortion if we use modern frameworks and concepts to describe ancient adumbrations of later discoveries. Leave the past as it was. We should not read it in the light of present concerns.

I would argue to the contrary that we cannot but read the past with eyes on the present. The past is not some fixed and static entity, stretched out conveniently like a corpse on the examination table to be dissected and studied in a hermetically sealed chamber.

Indeed, Herbert Butterfield, the constitutional historian who gave us the phrase “whig interpretation of history” in 1931, himself believed that “we are all of us exultant and unrepentant whigs,” and described his discipline not as the study of origins, but as “the analysis of all the mediations by which the past was turned into our present.”

The mediations of our immediate past have yielded a paradigm that sees Nature as a mechanism, a machine even, whose levers we humans can pull to produce outputs that we like or think advantageous. The machine paradigm is founded on a reductive approach to scientific inquiry—a focus on working parts at the expense of emergent wholes.

Reductionism, however, is not a bogey man, as it’s often presented in some circles. It’s how hard science works—to reduce a problem or object of investigation to its simplest form by analysis and experiment—and it has produced impressive results. It has a role to play in any worldview.

The problem is that the mechanistic approach is fundamentally an anthropocentric one, where, in the words of an old sophist, Protagoras of Abdera (485–415 BCE), “the anthropos is the measure of all things.” Anthropocentrism and its benevolent corollary, old-fashioned humanism, has produced some good results, too, first and foremost the gradual recognition and protection of human dignity and human rights.

In fact, Butterfield got his phrase from a tendency among early practitioners of English constitutional history, who belonged politically to the Whig party, to see the broadening of human rights as a realization, in the fullness of time, of feeble gropings in the past.

The trouble with anthropocentrism, though, is that it has also created the Anthropocene. We now live in an age where human-induced harm is arguably greater in aggregate than human-produced good, threatening to make the planet unlivable not only for us, but for other species, too.

This is also the conclusion reached by Swiss philosopher Dominique Bourg and his colleague Sophie Swaton, a philosophically inclined economist, in their magnificent book Primauté du vivant (2021), whose title, “Primacy of Life,” a play on the French legal phrase for the “rule of law” (primauté du droit), recalls Ruskin, and whose subtitle, “An Essay on What Is Thinkable” (Essai sur le pensable), points to the possibilities of a way forward.

Bourg and Swaton argue for the view that the conditions for consciousness are embedded in the phenomenal world. Forests, coral reefs, DNA, and the like all “think”” they show, in their own way. Human self-awareness is an extension or manifestation of the latent consciousness in all Life. It is an ancient idea that has been resurrected and bolstered with scientific findings by British psychologist Max Velmans as “reflexive monism,” a view akin in many ways to the philosophy of “panpsychism.”

To me those specific formulations are neither here nor there. When, however, Bourg and Swaton urge us to embrace a new paradigmatic relationship to living things, one that reenchants Nature, protects biotic communities as humans are protected with the long arm of the law, yet also affirms the kind of human activity that supports civilized life and leads to more just and stable societies, we are on the same page.

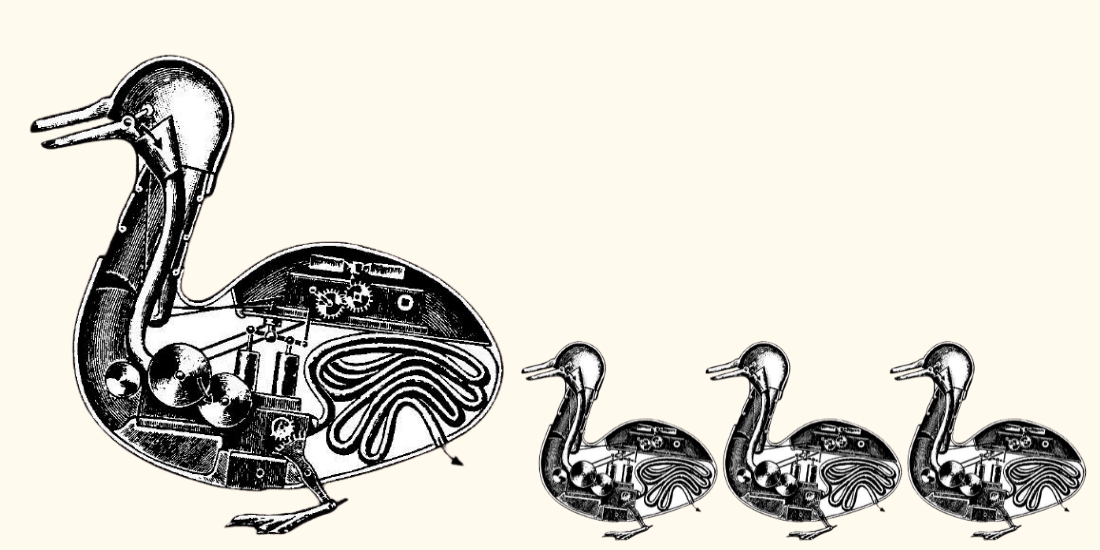

I teach a course called “How to Think About Animals,” in which we read T.H. Huxley’s classic paper “On the Hypothesis That Animals Are Automata and Its History,” published in the journal Nature in 1874. Huxley (1825–1895), nicknamed Darwin’s Bulldog for his fierce defense of Natural Selection against the counter-tide of Victorian sentiment, recounts sympathetically how one of the greatest scientists of the seventeenth century, René Descartes (1596–1650), could have come to the unfortunate conclusion that animals are nothing more than unconscious machines.

Against this notion—a logical outcome of an anthropocentric, mechanistic view of Nature—Huxley argues that nonhuman animals are, rather, like us, “conscious automata.” While Huxley’s conclusions on other matters may fall short of satisfactory, he puts his finger on a button that should signal our attention: consciousness is a real wrench in the works, so to speak.

The perhaps irresolvable problem that besets us all, arguably the font and fundament of all our other problems, is that humans are both a part of Nature, yet, with our capacity for recursive thought and symbolic representation, can also stand apart from it. We need somehow to reconcile both conditions, what we might call singly the human condition.

Ancient thinkers seem to have understood this dilemma. Their injunction to follow Nature’s lead in deciding how to live and what courses of action to pursue is an attempt to resolve it.

To the charge that in valorizing this idea from the past I have resorted to cherry-picking the evidence I would reply that, well, cherries are delicious. Of course we should pick the ripe, low-hanging fruit. And we should preserve it.

Some shared, fruitful ideas that I see as worth preserving from the ancient texts discussed in these sermons—works by Lucretius, Plato, Heraclitus, Aristotle, Diogenes, Seneca, and their various epigones like Whitman, Uexküll, Thoreau, Ruskin, and Bataille—are a clarion call to simple, mindful living, a recognition and embracing of natural limits, an affective deference to Nature’s organization and natural laws—indeed its awesome beauty—and an underlying nonreductive physicalism, founded on empirical, rational enquiry, that acknowledges unseen realities.

That’s a lot of -isms and some sweeping generalizations, I realize. Some may doubt that Plato was a physicalist, or that Diogenes cared a hoot. For my own part I find myself falling back on the worldly wisdom of the human-turned-pig in Plutarch, Gryllus the Oinker, who chastised Odysseus and us all when he declared triumphantly on behalf of his animal brothers and sisters: “Nature is our whole concern.”

At the end of the monograph in which he presents the Umwelt concept to general readers, “A Stroll through the Worlds of Animals and Men” (1934), Uexküll deploys his signature idea to satirize, albeit lightheartedly, his fellow scientists.

Each engages with Nature through his or her own limited sensory receptors and morphology—the astronomer explores his universe with the bug eyes of a telescope, the chemist describes hers with an alphabet of elements from the Periodic Table, and so forth. “Soap bubbles” Uexküll calls the various Umwelten of this world—ephemeral enclosures with delicate membranes that differentiate one organism from another.

The image recalls (unintentionally, it would seem) the Roman agronomist-cum-antiquarian Varro (116–27 BCE), who, in his eighty-fifth year, dedicated a fine guide to agriculture, the Res Rusticae (“Country Matters”), to his wife Fundania, who had just purchased a farm of her own: “If humans are bubbles, as the saying goes,” Varro apologizes to her in advance of his efforts, “an old man is a bubble all the more.”

Old or more recent, are the bubbles of our environments impermeable? The very discovery of their existence suggests that they are not. We can step outside of our own bubbles to understand other worlds around us. By that same token the capacities that have alienated us from Nature are the very ones that can reinscribe us back into it.

Whether we want to live in and with Nature and whether we will ever do so remains to be seen. One thing, however, is certain: bubbles inevitably burst, and when they do, they’re gone.

______________________________

Excerpted from Following Nature’s Lead: Ancient Ways of Living in a Dying World. Copyright © 2025 by M.D. Usher. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.