For centuries, as Cossacks and fur traders tentatively planted Russian flags along the Amur River, Amur tigers and their habitat were protected to the south from human encroachment by a dense barrier of interlocking trees. Called the Willow Palisade, this was a seven-hundred-kilometer-long double wall, planted in northeast China in the middle of the seventeenth century by the Qing dynasty to demarcate the southern extent of their homeland. The Qing—descendants of the Jurchen Empire, destroyed by the Mongols in the thirteenth century—regrouped to eventually capture Beijing and rule China for nearly three hundred years.

Article continues after advertisement

Their ancestral lands, including the Ussuri and Sungari river basins and the Changbai Mountains, were considered the cradle of their civilization and a place to be protected from outsiders. This area, in present-day Jilin and Heilongjiang Provinces, was also prime Amur tiger habitat. The palisade started near the eastern terminus of the Great Wall and pushed to the northeast, ending somewhere between the contemporary cities of Changchun and Jilin.

The palisade itself consisted of two earthen berms a meter tall and a meter wide, with a deep, three-and-a-half-meter-wide trench between them. Willow saplings were planted along each of the rises, with the branches of one tree tied to those of its neighbor so that they would grow together in a thick braid. Controlling passage through the palisade were twenty-one ornate gates, spaced approximately fifty kilometers apart, meant not only to curb immigration of Han Chinese and Koreans into Qing lands but also to limit movement of any natural resources out. The forest and its valuable ginseng, deer antlers, and lumber were for the Qing alone.

The forest and its valuable ginseng, deer antlers, and lumber were for the Qing alone.

One of the palisade gates, called Weiyuanbao, protected access to the Shengjing imperial hunting reserves, a vast tract of wooded hills set aside for exclusive use by the emperor, his family, and the empire’s soldiers. Nearly ninety thousand square kilometers of northeast China, an area larger than all of contemporary Primorye, was set aside for warriors to pursue game and demonstrate skills before their ruler.

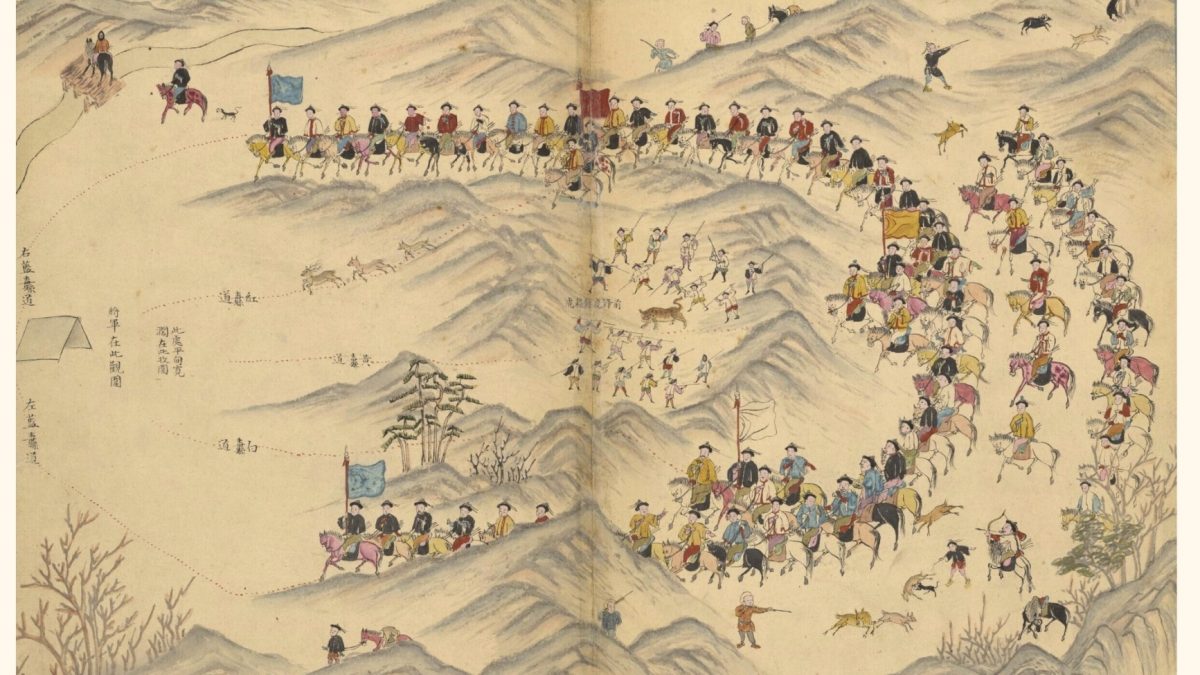

The hunts here were true spectacles: thousands of soldiers on horseback, armed with spears and arrows, converging twice a year in game drives. In one of the hunts, called a xingwei, horsemen armed with bows formed a vast semicircle to push wildlife ahead of them. This structure of the hunt gave animals the ability to flee if they kept their wits and moved straight ahead, but any caught in the confusion were surrounded and overwhelmed.

While these exercises focused on deer and wild boar, hunters also pursued tigers, their striped, flexible forms clearly depicted in several nineteenth-century illustrations of Shengjing hunts. The imperial hunting reserve was well managed, with hunts rotating among sixty-three subunits so as not to overharvest animals from any one location.

Russian imperial aspirations in the middle of the nineteenth century may have caught the Qing by surprise, as there was no palisade to protect the cradle of their civilization from the north. The Russians, seeing other empires gain ground in northeast Asia, were impatient for their own influence in the Pacific.

In addition to hunting for sport and pest control, Russians quickly figured out how to capture tigers alive.

Despite a 1689 treaty that placed the Sino-Russian boundary some seven hundred kilometers north of the Amur River, the unequal treaties of 1858 and 1860 drew the Russians right to the Amur and Ussuri Rivers, the edge of the Qing motherland. As Russians populated these borderlands, the Qing responded in kind, reversing their immigration policy to flood their side of the Amur River with settlers, seeking to form a living border, one that they hoped would deter any further territorial aspirations the Russians might have.

By the 1870s, all lands within the Shengjing imperial hunting reserves—which for two hundred years had protected tigers, their prey, and their habitat—were dotted with human settlements, the skies above them gray from brushfires as forests were converted to fields or cleared for homes. Tigers, pushed north and east to escape the incoming waves of Han settlers and fire, did not find sanctuary on the far side of the Amur and Ussuri Rivers. This was not a xingwei game drive in which animals had a chance of escape. Instead, they were met by a wall of armed Russians.

In addition to hunting for sport and pest control, Russians quickly figured out how to capture tigers alive. Some, such as Ignat Trofimov and Ivan Kalugin, made these dangerous captures a family business; their dynasties would operate for decades, satisfying demand from the zoos and circuses of the world eager for roaring tigers to entertain paying guests.

Their strategy was to follow tracks of tiger families in the snow—a mother with young cubs. They would scrutinize tracks to see where the cubs were walking. Older and therefore more menacing cubs wandered alongside their mother, while smaller cubs stepped directly in their mother’s footprints.

These younger cubs, while still hazardous, lacked the experience to fend off their attackers when confronted by skilled trappers. The men might follow such tracks for a week or more to catch up to the animals, then disorient the tiger families by releasing dogs or volleys of gunfire, causing the cats to scatter. Trappers would ignore the mother and follow the cubs, running the exhausted young creatures down, pinning them with forked sticks, binding them with shackles, and then shuttling them to markets for sale.

Ever since settlers, both Russian and Chinese, filtered into Amur tiger forests in the middle of the nineteenth century, the fate of these cats has been linked to human attitudes. Amur tigers have been caught in this strange space between two empires—skirting the human-drawn line superimposed over forest and mountain in northeast Asia.

For 170 years, tiger numbers have fallen and risen on both sides of the border as feelings toward these creatures have evolved: they were something to be feared, then hunted, and finally protected. The Siberian Tiger Project and its allies were at the center of the Amur tiger conservation renaissance. The project became a model of how like-minded individuals focused on a shared vision of a future with tigers could work together and enact meaningful change. How the project began, and what it accomplished along the Sino-Russian frontier, is a remarkable tale of innovation, camaraderie, adventure, and, ultimately, inspiring success.

__________________________________

From Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China. Used with the permission of the publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2025 by Jonathan C. Slaght.