My first point of contact with Agrippina the Younger’s story was her murder. I was on my commute, listening the radio, when a voice wended from the speakers, describing the dreadful details of her death. Or I was in a museum, her corpse suddenly before me on an enormous canvas, fixed in a goldleaf frame. Or I read of it—a searing line of it in a wall of footnotes. Or perhaps someone (an historian? a factoid-loving friend?) said it offhand. Whether through eye or ear, Agrippina’s death wormed its way in. What I do remember: Agrippina the Younger was murdered by her son, and he cut her open to look at her womb. His desire to see his point of origin to more fully understand his own magnificence of course only illustrated his monstrousness.

Article continues after advertisement

The source of this detail remains lost—a short-lived spark that fell on a fuse. Like so much of history, I will simply never know. Maybe because this story changed the course of my life for a decade, my brain threw it under a veil, rendering it impossible to remember.

Agrippina’s violent assassination was grotesque, bordering on the absurd. Her son the Emperor Nero’s order so baldly overlaid to a woman’s maternity with her vulnerability it blew my mind. Who was she? I thought. What could she have possibly done… (the end of that question, unuttered even to myself: to deserve that?). I had enough experience as a creative thinker to know to follow the heat of curiosity. So, hoping to scratch out a poem about Agrippina, I began to read. It was then I found this was just one version of Agrippina’s death—and after several failed attempts. There was another with poison (she survived), then a self-sinking ship (she survived this too). In yet another, she boomed to her assassin, “Strike here,” pointing to her center, “strike here, for this bore Nero.” And with that, I was suddenly tumbling into the rabbit hole of this remarkable woman’s life.

Agrippina was an oddity of a different sort: to them, she was power-hungry, masculine even. She wanted power, attaining it at a level even men of her era clamored for.

According to ancient Roman annals, Agrippina married three times and murdered two of her husbands. She killed or exiled her enemies. Through sex, murder, and manipulation, she became empress, positioning her son into the seat of emperor and using him as a prosthetic to run the empire. Modern historians largely contest the most scandalous of these claims. Yet despite Agrippina’s undeniable influence on Imperial Rome, there remain few verifiable details about her—and these largely circle around her male family members (along with having Nero for a son, the dastardly Caligula was her brother).

What is certain is the Romans of her era were bent on villainizing Agrippina due to one of the few provable facts of her life: she was a woman who gained and wielded power through her own deliberate actions. While many ancient Romans were slandered via sexual misadventure (see: Messalina), Agrippina was an oddity of a different sort: to them, she was power-hungry, masculine even. She wanted power, attaining it at a level even men of her era clamored for. She managed to realize this impossible goal in a society in which women were legally second-class citizens.

Considering her brilliant political mind, I struggle to bank my rage over the enduring obsession with Agrippina’s body. Her death and Nero’s birth loom large in ancient literature, but the specific details from some turns my stomach. Pliny, for example, made claims about Agrippina’s teeth. “Those females who happen to have two canine teeth on the right side of the upper jaw, have promise of being the favourites of fortune,” he wrote, “as was the case with Agrippina.” And then, like a game of historical telephone, we learn through Pliny that Agrippina wrote three memoirs (!), one of which describes the ordeal of Nero’s breech birth. Pliny provides no quotation, listing it under “of prodigious and monstrous births.” So many of my poems subsequently tried to chase the woman who built a secret entrance into the Senate so she could listen in on discussions otherwise reserved to men—a woman who described giving birth in the autobiographical form usually used to depict military conquests.

As I entered the final stages of editing my manuscript about Agrippina and my obsession, I learned my fixation’s origin story—how Nero murdered Agrippina and looked inside her corpse—was a fiction. Even in the opaque uncertainties of ancient history, we can pinpoint when people made it up whole cloth. In the illuminated texts of the medieval and early Renaissance periods, artists decided to rachet up the horrors of Agrippina’s matricide.

At first glance, in the illumination above it seems perhaps Agrippina is in charge, pushing her uterus forward—I imagine her shouting “Strike here!” But then, no. Her arms are tethered to a post, Nero’s pointing finger perfectly aligned with the blade drawing her blood. Another illumination takes out any of the uncertainty of Nero’s interests. Where in the former (figure 1) everyone is turned toward Agrippina, the center of attention, here in figure 2 she is already dead with no one paying her any mind. Agrippina’s insides are simultaneously vaginal and a mesmerizing spiral. The scene is absurd to the point of funny—four men in tight quarters with an exposed corpse and yet affably disinterested. (There are others similar to these illuminations—and others still, somehow more gruesome.)

The painters two centuries after the French and Italian artists of the late medieval period seemed to reread the ancient histories. Nero “hurried off to view the corpse, handled her limbs, criticising some and commending others,” wrote Tacitus. According to Cassius Dio, Nero said, while looking Agrippina’s body, “I did not know I had so beautiful a mother.” Luca Ferrari’s Nerone davanti al corpo morto di Agrippina began a new approach in the 17th century, followed by Pietro Negri not long after. The paintings point, some more quietly than others, at the fabricated rumor that Agrippina was so desperate for power she seduced even her son.

As Jennifer Nelson, the poet and scholar of early modern European art, told me, the medieval illuminations of Agrippina’s murder were more like crass jokes “that are then supplanted by a baroque indulgence in the sensuality of her corpse.” In each, Agrippina is dead, luminous, in opulent jewelry or surrounded by fine furs and cloths. In each, Nero looks. He is putting her on display, or acts like her assassination is a surprise, or is trying to absorb the reality of her death. In each, her breasts are exposed, any other fabric leaving little to the imagination. In some, there is blood. In some, Nero lifts fabric as if he is peeking at something, like a child uncovering a forbidden secret.

When I delved into the works of Tacitus, Cassius Dio, Suetonius—the ancient chroniclers of the lives of imperial figures who overlapped with Agrippina’s—the empress’ absence stunned me. Despite her connection by blood to illustrious Roman nobility, Agrippina would disappear almost as swiftly as she was named. After a quick description of one of her marriages, or the birth of the future monstrous emperor, she evanesced behind the foreground of imperial Roman men. Agrippina’s story was one that was simultaneously vast and absent. It contained the entirety of the Roman Empire’s lineage, yet her appearances were often vague or fleeting—a small whirring part within an expansive system of patriarchal historical narrative. While essential and vital to that system, she was overlooked. Agrippina’s three memoirs were lost in the two millennia since her death. Her desire to tell her story from her perspective was so important to her, yet what endures are words from the male historians who lived only after her assassination. And then the painters, scandalized by those words over a thousand years later, took up their gold leaf and paintbrushes.

*

Of all the renditions of Agrippina I have come across, my favorite is by Gustav Wertheimer entitled Der Schiffbruch der Agrippina (The Shipwreck of Agrippina) from 1874.

In Wertheimer’s painting, Agrippina’s friend and attendant Acerronia Polla clings to her for dear life as the opulent ship built to fall apart is doing its dirty work. Agrippina throws a protective arm around Acerronia, flinging back the silks while the waves crash around them. In the shadows to the right, we see Acerronia’s future—after she shouts to men pretending to be the former empress so Acerronia might be saved. They stab her to death. Agrippina immediately realized the sinking ship was an assassination attempt. Wertheimer shows her in the grip of terror. Even afraid, she is powerful. I can see her try to work out how to get out of this alive.

Agrippina stayed quiet. She swam. A worried crowd had assembled on shore, knowing the former empress was on board the ship that was suddenly sinking. Once she safely emerged from the water, they celebrated Agrippina’s survival. Not long after this wild brush with death, men came to her with blades. I imagine (hope) one detail, at least, was not invented. That she named who ordered her murder and said, “strike here”—claiming some power even at the moment of her death.

__________________________________

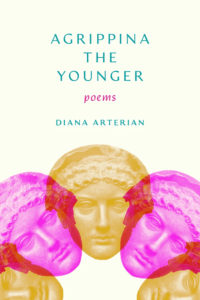

Agrippina the Younger: Poems by Diana Arterian is available from Curbstone Press, an imprint of Northwestern University Press.