On April 14, 1936, twenty-year-old Orson Welles directed his first major play. The production was an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth with an all-Black cast. Debuting in Harlem’s storied Lafayette Theatre on Seventh Avenue at 132nd Street, the play sold out every one of its 1,223 seats. Ten blocks on either side of the theater had to be shut down due to the overwhelming crowds, and a police escort was required to lead the ticketed through the throng. The play went on to enjoy a sixty-four-performance run before touring the country with its astounding 110 cast members. Though Welles is perhaps most remembered for directing and starring in the 1941 film Citizen Kane, which earned nine Academy Award nominations, it was his sensational—and Black—Macbeth that first made him a star.

Article continues after advertisement

In the original Macbeth the title character kills the king of Scotland so that he can become the reigning monarch. As king, Shakespeare’s Macbeth meets a tragic end when civil war erupts and his rival Macduff beheads him. It was not the fictional Macbeth’s death, however, that so attracted Harlem theatergoers. Inspired by the life of Haiti’s first and only king, the formerly enslaved general Henry Christophe of Haitian revolutionary fame, Welles set his Macbeth in the early nineteenth-century Kingdom of Haiti rather than Shakespeare’s original medieval Scotland, and most of the play’s action took place within the backdrop of a large stone castle meant to replicate more King Henry’s famous palace at Sans-Souci than Macbeth’s royal Dunsinane.

Erected in the early 1810s, Sans-Souci (meaning “without worry” in French) is located in the tiny hamlet of Milot, Haiti, just south of the northern coastal city of Cap-Haïtien. Partially destroyed by a magnitude 8.1 earthquake in 1842, today the palace doubles as a UNESCO World Heritage site, along with King Henry’s enormous, fortified castle, the Citadelle Laferrière. Called the Citadelle Henry in the king’s day, Christophe’s famous fort, which survived the deadly quake, sits atop one of Haiti’s highest mountain peaks peering all the way out to the Atlantic Ocean. Deemed the largest fortress in North America and widely hailed as the “eighth wonder of the world,” the Citadelle is also the location of King Henry’s grave. Like Macbeth, King Henry met his tragic end when a civil war broke out and the aristocracy turned against him. Yet unlike Macbeth, King Henry took his own life.

In many respects, Christophe lived more the life of a Shakespearean antihero than the Bard could ever have conjured. Born to an enslaved mother on the British-claimed island of Grenada, before his twelfth birthday Christophe found himself in North America participating in the American Revolutionary War. Trudging through the swamps of Georgia, he suffered a wound to the leg while French forces fought the British at the Battle of Savannah on October 9, 1779. By the 1780s, Christophe was still living a life of precarity, but now he was on the French-claimed island of Saint-Domingue, which had the reputation at the time of being the cruelest, and richest, slave colony in the Caribbean.

Understanding the nation King Henry tried to create requires recognition that the world he lived in was one where Haiti’s freedom was constantly under threat.

First visited by Christopher Columbus in 1492, the island was renamed La Isla Española (Hispaniola) by the Spanish who subsequently decimated the native population and instituted a plantation society based on enslaved African labor. The French formally took over the western side of the island in 1697 per the Treaty of Ryswick and renamed it Saint-Domingue. Saint-Domingue quickly became France’s most prized overseas possession, producing more sugar, coffee, cotton, and indigo than any other colony in the world. Employed at a hotel in the colony’s most bustling city, Cap-Français (later Cap-Haïtien), young Christophe witnessed the constant comings and goings of the slave ships that by 1791 had transported more than 1.3 million Africans from the continent to toil in soul-crushing conditions. He also had a front row seat to conversations about rights of citizenship for the colony’s tens of thousands of free men of color, many of whom were also enslavers.

French slave codes initially allowed white men to marry African women after converting them to Catholicism, thereby granting the latter free status. The generations of children that resulted from these unions became known as the gens de couleur libres, or free people of color. Determined to preserve some semblance of division between the free people of color, descendants of enslaved African women and white male French colonists, the French passed a series of ordinances depriving free Black people and their mixed-race counterparts of equal rights, including access to the colony’s schools and pensions. Some free Black families consequently sent their male children to France to be educated. In France, many of these free men of color witnessed the tumultuous storming of the Bastille prison in July 1789 and watched with hope as the revolutionary rhetoric of liberty, equality, and fraternity eventually led the French populace to overturn monarchical rule.

In August 1789, France’s revolutionaries issued the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, in which they announced, “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” While the emergence of this idea resulted in the creation of a National Assembly that was to initially govern alongside the king of France, this statement had implications back in Saint-Domingue as well. Armed with article 2’s assertion that “liberty, property, safety, and resistance to oppression” were “natural and imprescriptible,” Saint-Domingue’s hommes de couleur, or free men of color, insisted that the French government recognize them as equals.

The idea of a revolution capable of producing equality for all lingered in Caribbean air for the next two years, but little did the white colonists suspect that when the revolution reached Saint-Domingue, it would be led not by free people of color but by the island’s enslaved Black population.

Enslaved Africans (approx. 450,000) outnumbered both the white colonists (approx. 30,000) and the gens de couleur libres (approx. 28,000) by a ratio of nearly fifteen to one. The enslaved soon put this inequality to good use. The Black-led revolution burst forth on the night of August 22–23, 1791, in the northern plains of Saint-Domingue. By the middle of September, the island’s Black freedom fighters had destroyed more than a thousand coffee and sugar plantations, and forty thousand of the enslaved were in open rebellion. Eventually led by the famous general Toussaint Louverture, who, like Christophe, had previously been enslaved, the freedom fighters demanded immediate liberation. Complicating matters for all the island’s inhabitants, in January 1793 the French revolutionaries, who had abolished the monarchy to create a republic, executed King Louis XVI and then declared war on Great Britain and Spain. Subsequently, all three nations, England, France, and Spain—the foremost colonial powers in the Caribbean—wrestled for control over the most lucrative sugar colony in the Americas.

The situation took a dramatic and surprising turn in February 1794 when the French republican government, mired in war elsewhere in Europe as well, declared the abolition of slavery throughout all France’s overseas possessions. Viewing this as a decisive victory, Louverture and his troops, among whom was eventually Christophe, joined forces with the French to defeat the armies of both England and Spain.

By 1801, Louverture sat at the head of the colony under the title of governor-general. His self-satisfaction is captured by the following statement: “I’ve been fighting for a long time, and if I must continue, I can. I have had to deal with three nations and I defeated all three.” The French, British, and Spanish were not Louverture’s only rivals, however. In an extremely significant, but not often staged scene of his life, Christophe played an integral role—one he later came to fully regret—in the sequence of events that led to Louverture’s capture, arrest, and deportation by the French.

Just as Louverture assumed near-complete control over Saint-Domingue, the Corsica-born French general Napoléon Bonaparte rose to power in France. In 1799, Bonaparte had helped to overthrow the existing government to become his country’s first consul. Soon after taking over France, Bonaparte began plotting to defeat Louverture and reinstate slavery. In late 1801, Bonaparte sent his brother-in-law General Charles Victor Emmanuel Leclerc on an official expedition to Saint-Domingue. With thirty thousand French soldiers, Leclerc’s mission faced many obstacles. The formerly enslaved population had been free from slavery for nearly a decade and vowed to fight the French if they tried to bring it back. Ever cautious of the optics of such an enormous armed flotilla, while hovering off the coast of Cap-Français, in February 1802, General Leclerc wrote to Christophe, commander over the city, who also held the rank of French general. In the letter Leclerc demanded to enter the port while denying that in sending these troops, part of the largest expedition to ever sail from France, the first consul intended to reinstate slavery. Christophe rightly suspected Bonaparte’s deliberate display of military might. Unconvinced by French promises, he ordered Cap-Français burned to the ground after threatening Leclerc: “You will enter the town of Cap only once it has been reduced to ashes, and even on these ashes I will fight you.” Despite his overt obstinance, only a couple months later, in late April 1802, Christophe dealt a near-fatal blow to the revolution when he suddenly joined the very French forces he had previously and so ardently fought. His defection was followed by that of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who later led the freedom fighters to victory against the French and declared Haiti’s independence.

After he learned of Bonaparte’s July 1802 reinstatement of slavery on the island of Guadeloupe, Christophe, like Dessalines, performed another about-face and reunited with the freedom fighters who transformed the revolution’s mantra from “Liberty or Death!” to “Independence or Death!” The damage done by their previous defection was irrevocable, alas. Although Louverture had resigned from his position as governor-general of the colony in May, in June 1802 one of Leclerc’s generals tricked Louverture into a meeting, summarily arrested him, along with his wife and children, and then forced them all onto a ship destined for France. The French subsequently imprisoned Louverture without a trial in the Fort de Joux in the Jura Mountains near Switzerland. Louverture’s autopsy listed the date of his death as April 7, 1803. French doctors recorded the cause as starvation, pneumonia, and complications from an untreated stroke. Louverture thus never lived to see the hard-fought independence of the island he helped make free.

Christophe’s trajectory, in contrast, floated ever upward. On January 1, 1804, after the freedom fighters, now calling themselves the armée indigène, or the indigenous army, definitively beat the French, Christophe signed his name, along with more than a dozen other Black generals, to the Haitian Declaration of Independence. Later that year, the Haitian army made Dessalines emperor Jacques I of the newly constituted Empire of Haiti.

Even with independence declared, Christophe’s personal and political trials were just beginning. Shortly before he joined the armée indigène, Christophe sent his son, François Ferdinand, to Paris to be educated at the school Louverture’s sons previously attended. Witnesses claimed that after France’s embarrassing loss to Haiti, the French government retaliated by confiscating Ferdinand’s belongings and abandoning the child to an orphanage. Christophe’s son died penniless and alone on the streets of Paris in October 1805 at the age of only eleven.

One year later, another devastating loss visited the grieving father. On October 17, 1806, members of the emperor Dessalines’s own military shot him off his horse on a bridge just outside Port-au-Prince. The emperor died immediately, and afterward his assassins dragged his tattered remains through the streets of Haiti’s future capital. Two months later, the very conspirators who orchestrated the assassination ensured Christophe’s election to president of a new Haitian state, proclaimed to be not an empire, after the fashion of Dessalines, but a republic, after the fashion of the United States. Worried that Dessalines’s enemies might eventually force upon him the same fate suffered by his erstwhile friend and ally, Christophe refused to be sworn into office. Instead, he fled to the northern city of Cap-Haïtien and established a separate state, taking the ostentatious title of “President and Generalissimo of the Forces of the Earth and Seas of the State of Hayti.” Another general from the Haitian Revolution, Alexandre Pétion, whom Christophe blamed for the assassination, became president over the republic seated in the southwestern city of Port-au-Prince. These moves effectively sparked a violent civil war between the northern state and the southern republic.

Then, on March 26, 1811, President Christophe radically changed the trajectory of his country when he announced that he would take the title of king; he was crowned in June 1811. By 1813 the Kingdom of Haiti boasted an entire system of nobility, with hundreds of dukes, counts, barons, and chevaliers, and the king began living with his wife and three remaining children in the richly adorned palace at Sans-Souci, whose complex architectural details—including its elegantly manicured gardens, elaborate fountains, sophisticated irrigation system, and unique, domed cathedral—rivaled the most opulent structures of old Europe. Yet the arduous labor it took to construct Sans-Souci and the Citadelle—with rumors circulated that more than twenty thousand laborers died—led to charges that the New World’s first king merely brought to it old-world despotism.

King Henry’s reign came to a sudden and crashing end when he suffered a debilitating stroke that left an opening for the military and nobles to turn against him. Despondent, on October 8, 1820, the king shot himself in the heart. Ten days later, soldiers from the republic under the rule of Pétion’s successor, Jean-Pierre Boyer, executed the king’s youngest son and heir to the throne.

*

Since his death more than two hundred years ago, Christophe’s tragic story has interested a broad array of playwrights, artists, novelists, and filmmakers across the world. In early 1821, the first work of theater devoted entirely to Christophe’s rise and fall, Christophe, King of Hayti, was performed onstage at London’s Royal Coburg Theatre. The second run of the play, written by the British playwright J. H. Amherst, had the famous Black actor Ira Aldridge playing the king in blackface. But it was writers, readers, and performers from the early and mid-twentieth century who exhibited a near-continuous fascination with the story of the Haitian king and his short-lived kingdom.

The story of King Henry reveals a proud, determined, and self-sufficient country whose culture was admired around the world, but one at the same time whose freedom many nations sought to strangle.

The prolific Black playwright William Edgar Easton authored the first twentieth-century rendition of the king’s life to make it to the stage, when in March 1912 the acclaimed Black actress Henrietta Vinton Davis directed and starred in Easton’s Christophe, a Tragedy in Prose of Imperial Haiti at Lenox Casino in New York City. A famous white playwright, Eugene O’Neill, for his part, drew upon the lore of the Haitian king’s death by silver bullet in his celebrated Emperor Jones (1920), whose title character, Brutus Jones, was played by the renowned Black actor Paul Robeson.

In 1928, Christophe’s life gained new appeal offstage with John W. Vandercook’s Black Majesty: The Slave Who Became a King. Published by Harper & Brothers, Black Majesty was chosen as a “blue ribbon book” and introduced the Haitian king to thousands of international readers. Many were already primed with curiosity about Haiti’s history due to the United States’ ongoing occupation of the country, which began in 1915. Hardly devoid of 1920s-era racial stereotypes, Vandercook at least tried to humanize his subject. The foreword to Black Majesty plainly reads, “This is the life of a man. I have added nothing to the sparse records of old books and the fading memories that linger in the minds of men in his own country. Nor have I left anything out, except a few foolish, though extraordinarily common, legends that I found had no historical basis whatever.”

Another influential member of the public curious about the Haitian king was the Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, who purchased film rights to Vandercook’s book in 1930. Although Eisenstein’s movie was never made, he tapped Robeson, his chosen actor for the principal role in Black Majesty, to play Christophe in the second of his aspiring productions about the Haitian king, The Black Consul. During a public address in the Soviet Union after his final attempts to make that film failed, too, Eisenstein remarked that the story of the Haitian king was “like a Shakespearean tragedy,” with Christophe’s downfall occurring after a “breach between him and the Haitian revolutionary masses.”

Unable to quell his own enduring interest in formally playing Christophe after the failure of both Eisenstein’s productions to reach the screen, Robeson brought the Black Majesty project to a different Hollywood director, James Whale, who had worked with Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein of Show Boat fame. Whale, Kern, and Hammerstein in turn purchased the film rights to Black Majesty from Eisenstein. Robeson then told an interviewer from the New York Herald Tribune, “The most interesting thing I can see ahead for next season is the musical play that Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein may do, based on Black Majesty, the story of Emperor Henri Christophe, who built his great citadel in Haiti and defeated Napoleon’s troops. It sounds like great material, doesn’t it?” Unlike Welles’s Macbeth, Black Majesty the musical was never made either.

Welles’s success in bringing the tragedy of Christophe as the Haitian Macbeth to the stage was not without its own travails. During the four-month lead-up to opening night, there were many who doubted the feasibility of such a production. For one thing, Welles lacked experience. A white man from Wisconsin, Welles had primarily been a theater actor and had directed only a few smaller productions in England. That is, until his friend John Houseman (also white) of the Negro Theatre Unit of the WPA’s Federal Theatre Project convinced the unit’s co-director Rose McClendon, a distinguished Black actress, that Welles was the right man to bring Macbeth—the play that superstition says shall not be named in any theater—to Harlem. McClendon initially questioned whether the African American community would accept Welles as the rightful director of a Black Shakespearean production. However, McClendon relented after Welles’s first wife, Virginia Nicolson, persuaded her husband to turn the “Scottish play” into a Haitian play. Potential theatergoers were not so easily convinced. In the weeks before the debut, picketers repeatedly interrupted rehearsals. One overzealous protester attempted an unsuccessful knife attack on Welles himself. Yet opposition to the play seemed to evaporate just as quickly as it had materialized. Defying its many naysayers, the Haitian Macbeth became an overnight sensation.

Newspaper critics from across the United States generally extolled the adaptation. They expressed fascination for Welles’s substitution of Haitian Vodou for the play’s original and more nebulous witchcraft. This unheard-of transposition, with the attendant stereotypes about Haiti and Haitians that it brought to life, eventually earned the popular stage production the nickname “Voodoo Macbeth.” Welles’s comments about why he set in the Caribbean what one critic called his “geographically irreverent Macbeth” were in large measure responsible for the exotic nickname and for its association with the rise and fall of Haiti’s king.

When Bosley Crowther of The New York Times traveled to Harlem to interview Welles around ten days before the opening, Welles wryly remarked that the island setting of the play was not Haiti at all: “It’s like the island that The Tempest was put on—just a mythical place which, because our company is composed of Negroes, may be anywhere in the West Indies.” “As a matter of fact,” the director continued with a smirk, “the only point in shifting the scene from Scotland was because the kilt is naturally not a particularly adaptable costume for Negro actors.” Welles followed up this artful denial by explaining to Crowther, “The witch element in the play falls beautifully into the supernatural atmosphere of Haitian voodooism.” Welles went on to concede that the historical period and figures of his Macbeth were drawn after the kingdom and king of Haiti. “The stormy history of Haiti during and subsequent to the French colonization in Napoleon’s day—and the career of Henri Christophe, who became the ‘Negro King of Haiti’…and ended by killing himself when his cruelty led to a revolt—form a striking parallel to Macbeth,” Welles confirmed. “The costumes and settings of the production are therefore broadly in this period of Haiti’s grimmest turbulence.” Given Welles’s sources, these comments, particularly regarding the costumes, are not as innocent as they might seem.

Welles’s biographer Simon Callow has revealed that with his wife’s encouragement the Macbeth director “set to work with passion, researching the period and the curious figure of the gigantic Grenadian slave” and future king. The main source Welles relied upon was, in fact, a copy given to him by Nicolson of William Woodis Harvey’s 1827 Sketches of Hayti: From the Expulsion of the French to the Death of Christophe.

A Wesleyan preacher who missionized in Haiti from 1818 to 1824, Harvey had little sympathy, or respect, for King Henry and caricatured him and his nobility throughout the book. “All the officers, whatever their rank or character, were fond of dress to an extravagant degree,” Harvey wrote. “But in the expence [sic] of their garments, and the ornaments with which they were decorated, they far exceeded the desire of their sovereign, and often rendered their appearance ridiculous” and “supremely fantastical.” “Nor was it possible for an European to behold a negro thus arrayed without feeling amused,” he said. Of the king’s downfall, Harvey provided a résumé of Christophe’s character flaws: “If his talents were great, his faults were numerous and glaring. His love of wealth could be exceeded only by his love of pomp and display. The violence of his temper could not always be checked, even by considerations of policy. His cruelty increased, as his ambitious views extended. And the unlimited power which he at length acquired, rendered him, as it has done many others, jealous, capricious, and tyrannical.” Harvey concluded, therefore, “Though he was once numbered among the heroes of his country, and the benefactors of his race; the despotism of the latter part of his reign, unfortunately for his fame, has already ranked him among tyrants.” By drawing his understanding of the king principally from Harvey’s travelogue, and likely a string of others produced in the English-speaking world, Welles ended up making his career promoting what was merely another caricature of an actual person, a historical figure, and an important one at that.

A more faithful retelling of King Henry’s life would not emerge until the Haitian historian Vergniaud Leconte published the first substantial biography of Christophe, in French, in 1931. It was followed in 1967 by a mostly sympathetic English-language biography, Christophe, King of Haiti, loosely based on Leconte’s account and written by the British author Hubert Cole. But the truth is that those who encountered King Henry’s story in the twentieth century were more likely to be introduced to his life from fictional and dramatic portrayals.

The king of Haiti’s tragic death is one of the most dramatized, and sensationalized, episodes in Haitian history. The Harlem Renaissance-era playwright May Miller, drawing on Vandercook’s account, offered a romantic rendition of the king as a sympathetic family man outdone by his own ambitions in her 1935 never-staged one-act drama, Christophe’s Daughters, originally published in the collection Negro History in Thirteen Plays. In the final scene of the play, Christophe’s daughters, Améthyste and Athénaïs, and his wife, Queen Marie-Louise, are left to bear, with “half-choked sobs,” the burden of the king’s body and legacy.

If Robeson never had the opportunity to play the Haitian king onstage, another famous Black actor of the early twentieth century, Rex Ingram, did. In February 1938, Ingram starred in the WPA production of William Du Bois’s Haiti, subtitled A Drama of the Black Napoleon, based on the lives of Louverture and Christophe. Judging from reviews of the play, it was the story of Haiti’s king that once more stole the spotlight. The Amsterdam News reported, “Rex Ingram’s characterization of Christophe completely dominates the scene.” Later, the paper noted that the first five days of the play’s run surpassed the record set by Welles’s Macbeth with attendance that reached 4,376 seats.

The former director of the Haitian Centre d’Art and U.S. wartime spy, Selden Rodman, also put the tragedy of Christophe onto the stage in his three-act 1942 play, The Revolutionists, while in 1945 Dan Hammerman produced a highly political dramatization of the king’s life in his Henri Christophe written for the American Negro Theatre in New York City. Just before he kills himself in Hammerman’s production, the overwrought Haitian monarch reflects, “I don’t know, maybe it’s because a man has no right being a king in the first place.”

Yet it is Christophe’s wife who offers the king a final insight in the host Richard Durham’s 1949 two-part radio play about the king, Black Hamlet, which Durham wrote and produced for WMAQ out of Chicago. “You made your mistake in thinking your power came from yourself, and not the people,” the queen counsels in the moments before King Henry takes his life. “Rebels who won their freedom from planters would not hesitate to take it back from you.” And in what is perhaps the most blatantly racist of all the stage productions, the Scottish author James Forsyth’s 1975 play Defiant Island: A Play Based on the Life of Henry Christophe of Haiti, a character called only “Big Black” cries out just before Christophe shoots himself, with his head rolling to the ground, “I got chains, and you give me them.” After this, another character called Dahomey shouts, “He shoot himself! Hisself shoot hisself,” to which “Big Black” replies, as he seizes the fallen crown, “The man is dead! Ha!” The tendency of historians, journalists, and artists alike to not just ridicule Christophe in this way but to portray his downfall as both righteous and inevitable has obscured the intricate personal and political events that led to the king’s dramatic demise, making him one of the least understood heads of state in the history of the Americas.

For more than two hundred years some of the world’s most famous writers have searched in vain for a lesson (or warning) in Christophe’s reign. Christophe’s life was performed onstage in three plays by the Nobel Prize-winning Saint Lucian author Derek Walcott, Henri Christophe (1948), Drums and Colours (1958), and The Haitian Earth (1984); in Henri Christophe, the priest who crowned Christophe cynically declares of the kingdom, “God, what a waste of blood, these cathedrals, castles, built; Bones in the masonry, skulls in the architrave, Tired masons falling from the chilly turrets.” As for the king himself, Walcott referred to him in his book of essays, What the Twilight Says, as a “squalid fascist” who “chained [his] own people.” The Martinican writer Aimé Césaire, for his part, wrote in the prologue to the published version of his at times parodic dramatization of the king, The Tragedy of King Christophe (1963), “Sure Christophe was the King. King like Louis XIII, Louis XIV, Louis XV and some others. And like all kings, all real kings, I mean to say all white kings, he created a court and surrounded himself with nobility.” In a much later interview about the play, Césaire explained that he “portrayed” Christophe “as a ridiculous man” because he “wanted to plunge through the grotesque to find the tragic.” Yet it was the Swiss-born Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier’s The Kingdom of This World—with its translations into English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Dutch, Russian, and Chinese—that has perhaps played the most influential role in promulgating the popular vision of Christophe as an uncommon tyrant.

Carpentier added spectacular lore to prior depictions of the king to explain why most of Christophe’s men turned against him in the end. The king of Haiti was “a monarch of incredible exploits,” Carpentier wrote, before adding that Christophe cut the throats of bulls every day “so that their blood could be added to the mortar to make [his] fortress impregnable.” “The bulls’ blood that those thick walls [of the Citadelle] had drunk was an infallible charm against the arms of the white men,” Carpentier concluded. “But this blood had never been directed against Negroes, whose shouts, coming closer now, were invoking Powers to which they made blood sacrifice.” Carpentier claimed in the prologue that his marvelous realist novel, first published in Spanish in 1949 and then in English translation in 1957, was “based on extremely rigorous documentation.” However, judging from his almost entirely invented and historically inaccurate portrait of Christophe—among other obvious mistakes, Carpentier has the king’s death occur on August 23, 1820, rather than October 8—it seems that the novelist drew less upon serious sources than on the kinds of runaway rumors about Christophe’s reign that had been rampant in armchair sources for some time.

In 1894, long before the dramatic scene of King Henry’s death made it into twentieth-century plays and novels, a U.S. newspaperwoman, Fannie Brigham Ward of Michigan, having never traveled to Haiti, added a larger-than-life detail to Christophe’s story that has become a myth all its own. She said the king “shot himself with a silver bullet,” as if he were a werewolf who could not be killed by lead. Referring to King Henry as a “cruel potentate,” she finished her account by claiming that Christophe’s Citadelle, which she said “took sixteen years to build,” was undertaken with “such cruel treatment of the laborers employed upon it” that “30,000 persons perished in its construction.” “There is no doubt that from the dizzy heights of its topmost towers thousands of people were thrown by order of the King,” she concluded. Ward’s comments underscore that the most incredible and enduring mythology of King Henry’s reign remains that of his putative tyranny.

A 1942 article titled “Henri Christophe: The Black Hitler,” published in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, spared no hyperbole either. Elaborating upon a detail about the king’s suicide originally included in Vandercook’s book, Vincent Towne, the article’s author, sinisterly insisted that the king shot himself not with silver but with a bullet made of “solid gold,” after his “increasing beastliness and the avarice that had made him a multimillionaire led to an insurrection.” Towne had no qualms about comparing King Henry to Adolf Hitler, that murderous German fascist, driving force of the Jewish Holocaust. “Like Hitler, he was cursed by a sadistic taint,” Towne wrote. “One of his diversions was to watch several prisoners being flogged to death every morning while he ate a breakfast against a window overlooking the place of execution. Some say these executions were scheduled purely for his entertainment,” he wrote. Armed with such sensational journalistic and fictional sources, artists from across the world, one after the other, proclaimed in virtual artistic unison that King Henry had been nothing more than a despot who essentially re-enslaved his people.

A 1983 Spanish-language comic first published in Mexico and then in Bogotá, Colombia, called Fuego: Majestad negra, distributed all over the United States and Latin America (Ecuador, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Panama, Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala), illustrated the king of Haiti’s story over an astonishing 192 issues. In the final two issues of the comic, which took its title from Vandercook’s Black Majesty, the Haitian people celebrate the king’s suicide after they have ransacked and destroyed everything in the palace. “I hate everything that reminds me of the tyrant,” one man exclaims. “With this, tyranny ends,” another character remarks.

Christophe’s rise and fall thus tells not simply the tale of one man, and his personal journey from slave to king and the political turmoil that brought him down, but that of an entire nation still struggling to be free.

In his widely read 1995 book on the history of Haiti, Silencing the Past, the famous Haitian historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot acknowledged both the seeming ubiquity of writing about the Haitian king and the world’s somewhat uncanny fascination with him, dripping with simultaneous wonder and disdain. As he walked through Christophe’s enormous stone Citadelle, Trouillot paused to run his fingers over the marble plaque that marks the spot where the king is buried. “Here lie the remains of King Henry Christophe, the Civilizer, who died October 8, 1820,” reads the gravestone placed there in 1848. “I was as close as I would ever be to the body of Christophe—Henry I, King of Haiti,” Trouillot thought while standing in front of the plaque. He then tried to explain the ambivalent place that Christophe occupies in the Caribbean literary imagination: “The Society of King Christophe’s Friends, a small intellectual fraternity that included Aimé Césaire and Alejo Carpentier…were alchemists of memory, proud guardians of a past that they neither lived nor wished to have shared.” But just as with the other alchemists of his story, those Caribbean authors did not, with full justice, capture the richness of Christophe’s life. Instead, like Welles and so many others, they paid into quasi-supernatural fabulations while turning King Henry’s story into literary gold.

The prolific Haitian historian Hénock Trouillot, uncle of Michel-Rolph and fellow member of the Society of King Christophe’s Friends, suggested a more practical reason for King Henry’s illegibility, and infamy, in global political history. “At bottom, Christophe’s greatest mistake,” he said, “and that of his partisans, was to have disappeared too early from the scene, which is to say before the future historians of Pétion and Boyer’s republic, who were his most pitiless adversaries.” In suicide, Christophe could control his destiny, but he could not control his legacy. The British abolitionist William Wilberforce, friend and frequent correspondent of the king, acknowledged as much when he remarked, “Poor Christophe! I cannot help grieving at the idea of his character’s being left to the dogs and vultures to be devoured.” Vandercook concluded the same: “Christophe, as is often the fortune of great men, has been remembered chiefly by his enemies and the cruel and silly tales they told of him.” This is a problem of perspective that affects more than just the story of King Henry

Despite its rich and full history, Haiti is often discussed by foreigners within a singular frame that revolves around poverty and violence, corruption and disaster—a point readily demonstrated by a 1994 article printed in The Miami Herald during the second U.S. occupation of Haiti: “World’s Oldest Black Nation ‘Ruthlessly Self-Destructive.’” The article’s opening paragraph, skirting any historical reference to the United States’ first occupation, from 1915 to 1934, insisted instead on an anachronistic parallel between King Henry’s rule and that of Haiti’s murderous twentieth-century dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier (called Baby Doc), whose henchmen, the Tonton Makouts, brutally executed more than thirty thousand Haitians. “In 1811, it was King Henri I. In 1849, it was Emperor Faustin I. A century or so later, it was Baby Doc who called himself ‘President for Life.’ Leaders in Haiti have a habit of declaring themselves firmly in control—and for life—only to be toppled by murder, coup or fateful circumstance.” After two centuries of almost consistently bad press for King Henry—in which Haitian leaders in general have been accused of “national incompetence,” and the populace has been described as at once “progress resistant” and having “deep…in the psyche…a violence that goes beyond all violence”—telling fuller, more nuanced stories about Haitian historical figures remains an important challenge. As it turns out, the reality of King Henry’s life, as often happens, is far more complicated, and interesting, than the fiction.

In the early nineteenth century, Haiti was the only example in the Americas of a nation populated primarily by former enslaved Africans who had become free and independent. Other nations, including Haiti’s trading partners, adopted a determined stance to prevent abolition and their colonies from becoming free and so refused to recognize Haitian sovereignty. When France finally agreed to do so in 1825, it demanded the astounding price of 150 million francs for the act. To preserve slavery in its territories, Britain failed to officially recognize Haitian independence until 1838, when slavery was fully abolished in its colonies. The United States refused recognition until after the start of the American Civil War, when most of the southern states had seceded from the Union. Nevertheless, Christophe published trade statistics, which showed that despite their fear of his country’s influence on Atlantic world slave regimes, Haiti enjoyed thriving trade relations with plenty of nations, including Spain, Great Britain, Sweden, Denmark, the United States, the Netherlands, Prussia, and Bremen. Writers from the kingdom claimed that any nation whose merchants traded with Haiti had de facto acknowledged Haitian liberty and independence from France. It is a daunting paradox to consider that when Haiti had sovereignty in the early nineteenth century, no other nation was willing to officially recognize it. In contrast, today’s Haiti appears to be sovereign, but it remains under the colonial yoke in many ways.

While the contemporary media often portray today’s Haiti as a land of perpetrators and victims ever in need of foreign occupation—portrayals that only increased following the deadly January 2010 earthquake in Port-au-Prince and again after the July 2021 assassination of Haiti’s president, Jovenel Moïse—the story of King Henry reveals a proud, determined, and self-sufficient country whose culture was admired around the world, but one at the same time whose freedom many nations sought to strangle. Throughout King Henry’s reign, France tried repeatedly to “restore Saint-Domingue,” which meant to reinstate slavery and colonialism. Christophe insisted that every one of his labor reforms and all his laws, along with every physical structure he built, were meant to ensure that his country would never again fall under the yoke of French domination. King Henry’s laws adamantly forbade chattel slavery, outlawed colonialism, and created an economically robust, financially solvent Black state, one not dependent on the transatlantic slave trade. At the same time, understanding the nation King Henry tried to create requires recognition that the world he lived in was one where Haiti’s freedom was constantly under threat.

A caption under a photograph of one of the 365 bronze cannons located at the Citadelle displayed in a Colombian Cruises brochure from the 1930s, advertising a twenty-three-day cruise from New York to ten ports in Haiti, reads, “Waiting for an enemy that never came.” But come the enemies had, only their best weapon turned out to be imposing debt rather than firing cannons. Christophe was unequivocally against indemnifying France, and his death singularly opened the door for the French to force the Haitian government to pay for with money what they had already earned with their lives. In one of the most unfortunate episodes in Haitian history, France not only impoverished the Haitian people but got away with what may very well be the greatest heist in history. Even though in 1838 France reduced the indemnity it charged to Haiti to 90 million francs, a recent investigation by The New York Times confirmed that in the end Haiti paid France 112 million francs, or $560 million over more than a century (amounting to between $21 billion and $115 billion in total losses to the Haitian economy).

Christophe’s rise and fall thus tells not simply the tale of one man, and his personal journey from slave to king and the political turmoil that brought him down, but that of an entire nation still struggling to be free. Once one of the most popularly portrayed and well-known Haitian revolutionary figures in the world, King Henry remains as misunderstood now as in the past. Renewed attention to his reign might just restore him to his rightful place as one of the most important political figures of the nineteenth century whose downfall forever transformed Haiti’s position in the world.

__________________________________

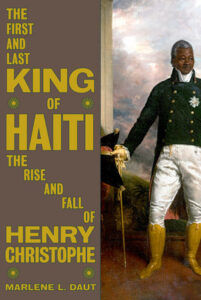

Adapted from The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe by Marlene L. Daut. Copyright © 2025 by Marlene L. Daut. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. The First and Last King of Haiti was shortlisted for the Cundill History Prize.