When I first told her I was in love with a woman, my mother insisted I had been “sought out.” She spat it like I’d somehow been lured down the wrong dark alley, falling into an untoward lifestyle by way of some demonic, lecherous dyke who could see I was an easy mark. It was not only untrue—finally attuned to what I wanted, I’d been the aggressor—but comical, how uncharacteristically convinced she was in her narrative about my private motivations. She couldn’t grasp that I’d simply left home and discovered my sexuality skewed sapphic (tale as old as time!).

Article continues after advertisement

But still, she felt hope: If I’d fallen prey to someone, I might still be talked out of it. After all, a lack of sense and self-control could be fixed. Did I want to speak to the family therapist? “You’re selling yourself short,” she said.

Like most, I didn’t come out with any fundamental knowledge of gay history, so it took some time for me to understand how cheap lesbians were when my mom was growing up in the 1950s. Back then, it was only twenty-five cents to purchase a life of pure depravity from the drugstore on the corner. For the brave and curious, that quarter would grant entry to French women’s barracks during wartime, the seedy dyke bars of Greenwich Village, the bedrooms of a North England sorority house, or a chance to ride “a tortured merry-go-round with this passionate Lesbian who jumped on young . . . and is too frightened to climb off!”

A quarter seems like a steal for a Choose Your Own Lesbian Adventure, but the real cost was all there was to lose should you be caught reading one. A preteen in the 1990s, my first palpably pulpy experience was seeing the cover of Bound at the local Blockbuster, staring at it lustfully without knowing why, wanting so badly to rent it but feeling just as strongly that I shouldn’t. I’d already intuited what it might say about me that I was drawn to a photo of two sultry, dark-eyed women wearing black leather jackets, rope-tied breast-to-breast, parallel pairs of lips parted in pouts. “In their world, you can’t buy freedom, but you can steal it.”

Mom may have been too square to read a pulp, but even that couldn’t save her from all the lesbians—or, as the books of the time had it, Lesbians. Cheap and easy, at least five hundred lesbian-themed paperbacks sold millions of copies nationwide between 1935 and 1965. That’s a lot of lesbians. In the fifties and sixties, these voyeuristic stories about lesbians could be purchased at all the same public venues you’d find in an episode of Leave it to Beaver or The Patty Duke Show, but you wouldn’t see Satan is Lesbian on television, nor her more successful sorority sister, Spring Fire.

Considered immoral, explicit homosexuality was forbidden on film courtesy of the Hays Code, and even the thinly veiled queer characters written by clearly sapphic authors of the McCarthy and Cold War eras were loath to be so bold for the cause. It was pulp novels that were the first to name lesbians on their covers with that capital L and sometimes plural, which indicated there was more than one and that they’d managed to find each other. That alone was enough to send a guy to his fly, or an isolated gay woman to imagining new possibilities.

It’s thrilling to know just how many different women discovered lesbian pulp novels at their corner store, and within them a name, proof of a shared identity, community, and history for the first time.

Hyperbolic and hypersexual, lesbian pulp novels could famously be identified by their suggestive titles and salacious, punishing taglines. Typically, at least two women appeared, generously endowed and in various states of undress, posed between sheets and slips of lust and terror. Accuracy was neither attempted nor attained. Even when characters were described with traditionally assumed Lesbian characteristics, such as masculine haircuts or butch demeanors, it was femmes only on the front, a loaded precursor to lesbian chic. Inside, storylines followed a formula with frequently dire consequences for the twisted woman who dared indulge in, by today’s standards, some pretty tame lovemaking.

More often than not, the lost women teased on the cover found their way back to heterosexuality, while the committed capital-L Lesbians faced certain death or ended up in mental institutions. This was the path taken to circumvent the same censors who’d given Radclyffe Hall hell with the 1928 publication of The Well of Loneliness, which also eventually received the pulp treatment once lesbians were all the rage: “Denounced, banned, and applauded—the strange love story of a girl who stood midway between the sexes.”

Not surprisingly, many of the pulps were written by straight male authors who let their crude imaginations run wild, and publishers, also straight and male, imagined the audience would be similar. However, a crucial part of the lesbian pulp readership mirrored the estimated one-third of pulp authors who were gay women. Their success highlighted how many readers were here for something beyond skimming the dialogue to reach the sex scenes, getting off, and trashing the books. It’s thrilling to know just how many different women discovered lesbian pulp novels at their corner store, and within them a name, proof of a shared identity, community, and history for the first time—even if, as Dorothy Allison once wrote, the Lesbian of lesbian pulp novels wasn’t exactly “true,” she was “true enough.”

In 1982, during the height of the Feminist Sex Wars, Allison, no stranger to trash or depravity herself, published an essay about the summer she spent house-sitting while exploring the owner’s secret shelves of saucy paperbacks poolside. She discovered the pulps hidden in a closet, their spines shamefully facing the wall, with titles like Valley of the Lesbo, Midnight Orgy, Make it Sting: “Well, what other kind of books do people keep in their closets?” The collection included all the typical softcore material, but then there was what Allison called “pseudo-porn,” the psychological and political paperbacks from authors explaining lesbianism from an outsider’s perspective of “exotic titillation and moral superiority.” Cringey as those “reports” could be, Ann Aldrich’s gay girl’s guide, Carol in a Thousand Cities, with its oft-depressing possibilities presented for any woman who chose to be a lesbian, sent Allison “back to the house for Kleenex and aspirin.”

Years later, we have the context that Ann Aldrich was a pseudonym for Marijane Meaker (aka Vin Packer, aka M.E. Kerr), and that the book’s title was a line pulled directly from her former girlfriend Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Price of Salt. The book that would later become the Oscar-nominated Todd Haynes film Carol was first released under Highsmith’s pen name, Claire Morgan, as the lesbian author lived mainly in the closet and initially had difficulty finding a publisher for her queer book.

Despite significant success with a hardcover debut and subsequent paperback, Highsmith’s experience—she wouldn’t take credit for the 1952 novel until 1990—underscores how discretion and secrecy were paramount to even the most successful lesbian authors. They, among many others, enjoyed a rousing sapphic life in secret, so it makes sense that many of the stories centered on women leading double lives and weighing the pros and cons of self-realization and sexual fulfillment within the constraints of capitalism and conservatism. In retrospect, the high stakes arguably heighten the excitement of seeing how these writers dared and got away with it.

From the poetry of Sappho to the journals of Susan Sontag, a case could be made for either lesbian porn and lesbian history. But like Dorothy Allison, I don’t find them mutually exclusive.

The remaining living legend of lesbian pulp is Ann Bannon, whose famed Beebo Brinker series brought Dorothy Allison back to her college dorm in Florida, where she read her copy locked in the dorm bathroom and harbored a crush on a girl down the hall who shared Beebo’s “close-cropped hair and an eternal sneer.” “When that girl disappeared from the dorm one mysterious night full of shouting and confusion, I ripped Beebo cover to cover and spread the pages over eight garbage cans and one dumpster,” Allison recalled. “Suddenly, I wasn’t reading porn, I was paging my own history.”

It’s fair that many queer women found lesbian pulp to be shameful, vulgar, and off-putting, fair to argue that the pleasure taken in our pains was neither positive representation nor adequate visibility, no matter who held the pen. It’s well documented that the publishers of The Ladder considered even (or maybe especially) the novels written by lesbians “trash,” and later they removed lesbian pulp entirely from their annual guide to The Lesbian in Literature. At least The Ladder reviewed lesbian pulp; nowhere outside of lesbian publications deemed them worth the low-grade pulp paper they were printed on. Some women seemed to read them begrudgingly, as what writer and Lesbian Herstory Archives cofounder Joan Nestle famously referred to as “survival literature.”

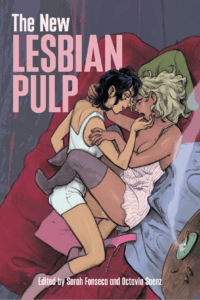

But to women like Allison, who could decipher enough truth from the fiction, Faithful to the heat of the originals, The New Lesbian Pulp maintains that same hot drip of anticipation and action on every page, with considerably fewer fucks to give. The modern-day protagonists are no longer the kind of lost souls my mother assumed I had been, what Allison described as “startled sleepyeyed women . . . taken by surprise when confronted with the sexual.” This anthology luxuriates in the sexual without the anxieties that plagued the original pulp fiction era. There is no longer the same preoccupation with being discovered as a lesbian at the center of the sex. The lesbian agenda is less taboo, making way for stimulating new circumstances between two women, including but not limited to heavy sexting coming to sweaty fruition in the back seat outside of an Orlando gay bar, or a simmering truckload of tension while hunting roadkill for revenge. Gay shame may be present, but it’s no longer filling the room with its stench.

And to The New Lesbian Pulp’s credit, sometimes it’s not even sex so explicitly, but rather an erotic energy exchanged in front of one’s husband, no less, as in Lorraine Hansberry’s story “Chanson du Konallis.” Initially published in 1958 under the nom de plume Emily Jones, it appeared in The Ladder, which is what’s so fun about this anthology: the chance to revisit, reframe, and expand lesbian literature in new ways, thanks to the hindsight and hot takes time has afforded us.

This anthology introduces trans femmes and butch-on-butch dynamics to the otherwise butch–femme, femme–femme interactions that only perpetuated confusion among sapphics in a wider society that had yet to differentiate gender from sexuality or allow for deviations from what one source defined as Lesbian, with a capital L. It’s exciting to find modern-day stories with the promise and payoff of the originals sitting alongside uncovered sapphic themed work from earlier writers like Alice Dunbar-Nelson, whose “Natalie” offers an enduring romantic friendship across race and class lines. How rich it is to see Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney included in this queer context, with an excerpt from her unearthed 1934 sapphic murder mystery novel, Walking the Dust, under the name L. J. Webb. The inclusion of Eve Adams/ Evelyn Addams serves as a fitting tribute to the Polish Jewish immigrant who both published her book Lesbian Love and ran a lesbian tea room in Greenwich Village before she faced entrapment and deportation in 1927.

Some original pulp fiction provided enough specifics to help readers navigate real-life lesbian locations, and The New Lesbian Pulp does the same. There’s dyke sex in an alley outside of Ginger’s and inside the bathroom at Metropolitan, just like there is every weekend in Brooklyn. Closeted women still cling to men they don’t love but believe they need, until they finally decide they don’t—and this time, there is no forced course correction at the end. Kink parties, a femme top’s funeral, an Airbnb outside of Palm Springs, rural family farmland, and performances at a jazz club—this anthology is not afraid to publish what others have refused. (See: “Cottonmouth.”)

By the end of her time at the house that summer, Allison decided to go home and put all her “Lesbian porn” out on display, wondering where all the books she’d published and still had yet to write would end up. Forty-some years later, and twenty-one years after coming out to my mother, I keep my lesbian pulp books directly under the television, where everyone can see them, alongside the rest of my “porn” collection— lesbian history, biography, fiction, photography, art.

Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic” shares space with Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence and copies of On Our Backs; work from writers like Andrea Dworkin, Michelle Cliff, Kathy Acker, Camille Paglia, Alice Walker, Nikki Giovanni, and Heather Lewis, each challenging in their ways. I go to bed with explicit images by Catherine Opie, Tee Corinne, and Kate Millett on my walls, a blue silicone facsimile of Eileen Myles’s fist taking up prime real estate on a center shelf for the curious to ask about. From the poetry of Sappho to the journals of Susan Sontag, a case could be made for either lesbian porn and lesbian history. But like Dorothy Allison, I don’t find them mutually exclusive.

I hope The New Lesbian Pulp will be proudly displayed in libraries and bookshops, pulled daily from bookbags, totes, and Telfies, spotted in profile photos on dating apps and in the text of personal ads (ISO a smokin’ top to dig her fingernails into my skin, shoot and skin a beaver, kill a man, and tie me up, not necessarily in that order. Must love snakes.) But in true lesbian pulp tradition, and at a time when book bans, censorship and anti-LGBTQ sentiments are at a fever pitch, some will inevitably read this anthology covertly, concealed in closets or under the bed. Whether out of shame or safety, they too are a part of the time continuum of lesbian history and porn.

_____________________________________

Excerpted from The New Lesbian Pulp, edited by Sarah Fonseca and Octavia Saenz, with permission from the Feminist Press.