What if it was legal for private universities to refuse to recognize graduate student unions? Since the return of Trump, that’s the threat against which many of us graduate student workers are organizing. Fortunately, in July 2025, we achieved a victory in Rhode Island that shows at least one path forward for labor unions across the country. All it took was collaborating with other unions to secure a change in labor law in the state.

The fate of graduate student unionization is more critical now than ever. Graduate students’ work is integral to the core research and educational missions of the university, which today are under threat. Yet, many graduate student workers are concerned that university administrators will respond to the attacks on higher education by passing the hardship on to their workers. We have already seen hiring freezes, funding cuts, PhD admission caps, threats of layoffs, and clampdowns on free speech from university administrations in response to recent federal policy decisions. The unfortunate reality is that graduate workers have to defend ourselves not only from Trump, but also from administrators, who would rather cut education and research than reconsider executive bloat, capital projects, and other boondoggles. In such an environment, university leaders may make a show of opposing Trump when funding is under threat, but they will happily align themselves with him in confronting graduate student workers.

University administrators would do so because, over the past decade, higher education has witnessed an extraordinary upswell of labor organizing, especially among graduate students. A significant boost came with the “Columbia decision” in 2016, when the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ruled that graduate student workers at private universities are employees, and, therefore, eligible to be represented by unions. Another boost came after 2022, as graduate student workers across the country looked to the example of the University of California academic workers’ strike. By 2024, 38 percent of graduate students were members of unions, making them one of the most densely unionized workforces in the country.

Today, however, the gains that graduate student workers have made are under threat. During Trump’s first term, the NLRB made noises about overturning the Columbia decision, ending any requirement that universities have under federal labor law to recognize graduate student unions. The NLRB failed to follow through then, but even the threat showed that the legal position of many graduate unions is precarious. With the second Trump administration cracking down on political activity on campuses, and right-wing groups like the National Right to Work Foundation pushing anti-union cases, it seems likely that graduate student workers’ right to unionize will soon be a target again.

In a moment when labor is under attack in education, the government, and the private sector, a united front is more necessary than ever.

I am a proud member of the Graduate Labor Organization (GLO)—part of the American Federation of Teachers Local 6516—at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Like other unions at private universities, we fear Trump overturning the Columbia decision.

In response to our concerns, Rhode Island’s labor movement stepped up, helping us find a way to protect our rights. Working with the Rhode Island AFL-CIO and our state affiliate, the Rhode Island Federation of Teachers, we realized that if graduate student workers were defined as employees under state labor law, our right to unionize would continue to exist, even if the Columbia decision were reversed.

This builds on precedents in Rhode Island and other states, who can extend to workers the right to unionize when federal labor law falls short. This was once the case for many nurses and continues to be for agricultural workers.

And so, in January 2025, language protecting this right—for graduate student workers to collectively bargain with their employers, universities—was proposed, as part of a package of state labor law amendments, supported by the Rhode Island AFL-CIO. We and other unions then mobilized to demand its passage in the state legislature: by writing letters, showing up to committee hearings, and pressuring elected leaders to make sure they knew just how important this issue was to our members. After months of advocacy, including over 100 letters written by our members, the bill was signed into law in July 2025.

Our experience at Brown suggests some lessons for labor strategy for higher education going forward. First, the victory in Rhode Island shows that, as the federal government’s labor and education departments come under attack, state and local institutions can be used to defend workers’ rights. This is particularly relevant in blue states like Rhode Island, where labor law has been less eroded by decades of neoliberalism and anti-union attacks.

Second, we learned that it is key to work with the broader labor movement. We benefitted greatly from the support of unions in our state, who understood why we were so concerned about the fate of the Columbia decision. Their initiative reminds us that the responsibility for defending workers under threat should not fall just on those directly affected. Established labor leaders should recognize the importance of the Columbia decision and graduate unionization to the broader labor movement—as ours in Rhode Island did—and move to defend workers’ rights. In return, it is essential that graduate workers come to the aid of other unions. In a moment when labor is under attack in education, the government, and the private sector, a united front is more necessary than ever.

Of course, legal changes like the one we secured are not the last word in this struggle. Our campaign was a defense of an already unequal status quo, in which workers still must be organized if they are to receive the respect, dignity, and fair compensation they deserve. But it is important to find ways to prevent the situation becoming worse. In the 1980s, the American labor movement was effectively broken by the Reagan administration, and workers have suffered the consequences for decades, showing how devastating union rollback is for workers.

If we are to live in a world in which universities emerge from the current moment as sites of thought, learning, and community—rather than investors and real estate developers with an educational branding—we cannot let higher education unions be defeated. We will need more organization and discipline, not just among graduate students, but among faculty, staff, and all other workers.

Our recent legislative campaign shows that through strategically chosen state-level reforms and close collaboration with other unions, we can set the stage for those future struggles. In the next fight, then, perhaps the balance of power will be a little less in the favor of those who seek to destroy higher education as we know it. ![]()

This article was commissioned by Dennis M. Hogan.

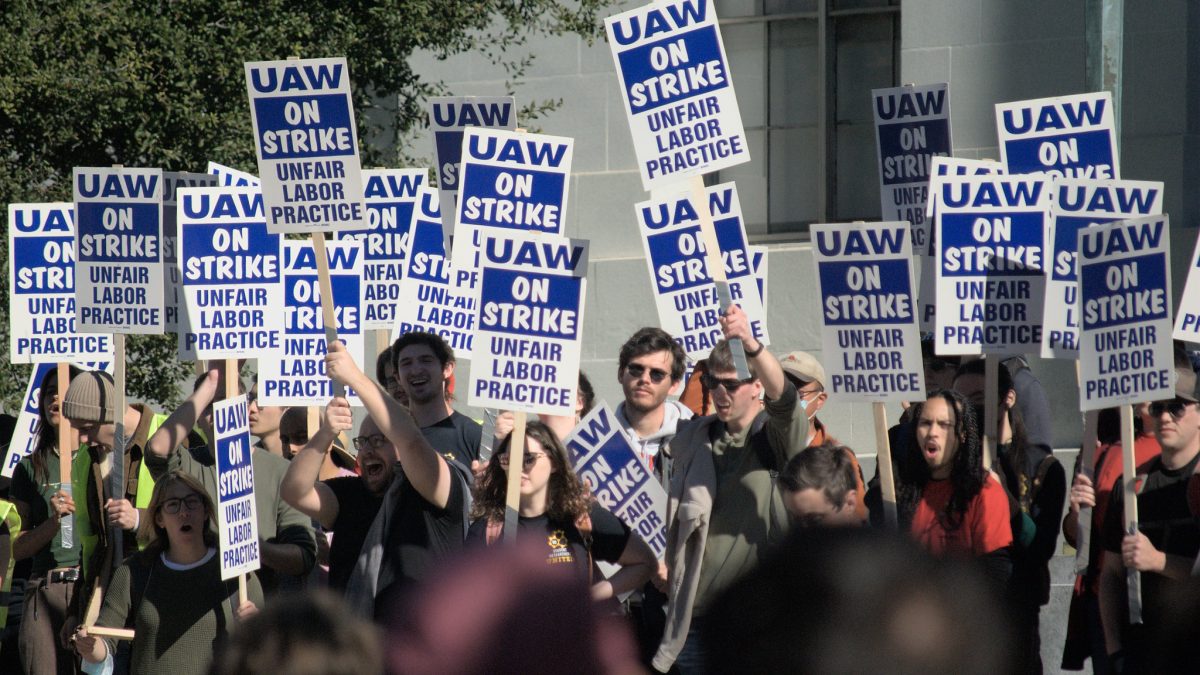

Featured image of the UC Worker Strike by Gabe Classon / Flickr Creative Commons (a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en”>CC BY 2.0).