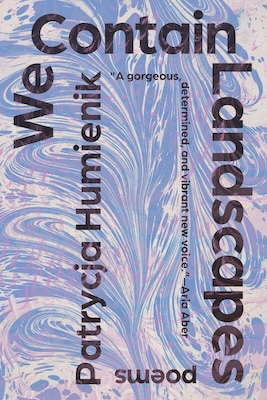

“Where do we go to find the myths that make us?” asks Patrycja Humienik in her debut poetry collection, We Contain Landscapes. This question, explored in Humienik’s crystalline voice that wields imagery with sensuality and aching precision, takes her readers to the mouth of a river, to letters exchanged with immigrant daughters, and to the gaps in memory that migration leaves behind.

The speaker of We Contain Landscapes is “unbearably present. Permeable to the world,” as she interrogates familial inheritance, place, and beauty itself with devotion and candor. Ultimately, these questions about belonging and desire prove to be unanswerable; yet there is something sacred in the asking, and this is the space where Humienik’s poems urge us to linger: curious, attentive, questioning.

In the epistolary spirit, Patrycja Humienik and I corresponded via letter over the course of a few months about rivers, surrendering to desire, and writing as a collaboration with time.

Ally Ang: The “Letter to Another Immigrant Daughter” poems were among my favorites in the book, in part because of the tenderness & intimacy between the speaker and the various addressees, and in part because of how these exchanges give the speaker an opportunity to ask questions of memory and intergenerational loss that resonate deeply with me as the child of an immigrant. Your note says that this series grew out of an epistolary exchange with the poet Sarah Ghazal Ali; can you share more about how the series began, and can you speak to the role that community with other immigrant daughters has played in the making of this book?

Patrycja Humienik: Sarah and my epistolary exchange began back in May 2021, before we’d even met in person, after taking a virtual class together with Leila Chatti. I was, and remain, compelled by Sarah’s attentiveness to image and sound. Via a flurry of texts and voice notes, we bonded over shared grappling with questions of lineage, inherited faith traditions, omission in immigrant family stories, and the limits and possibility of the lyric.

Relationships with other immigrant daughters have been crucial to making this book. Reaching intragenerationally gave me the space to articulate questions, longings, that I have been unable to pose intergenerationally. While I’ve been grateful to think together about daughterhood, my writing and life are nourished by relationships with children of immigrants across gender. The epistolary impulse throughout the book is aspirational, too—I want to be in conversation with my beloveds for years to come, beyond this first book.

AA: The most striking recurring image in WCL is the river, which appears both literally & metaphorically, transgressing borders, evading possession, carrying life through the land. In the call for submissions for The Seventh Wave anthology “On Rivers” that you edited, you write, “I return again and again to rivers, real and imagined.” What role have rivers played in your life & in shaping your poetics? Did you always intend for rivers to be an anchoring image in this collection, or did that develop organically?

PH: Rivers are a heartbeat of WCL, and core to my preoccupations and obsessions as a writer and artist beyond this first book. I didn’t plan anchoring images for the book—I find I cannot write that way. My love of rivers, though, is eternal. It’s impossible for me to look at or be near a river and not think of both the self and the collective, of interiority and ecosystems. Rivers at once ground and destabilize any questions about time, movement, possession, scale, and interiority. To me, the river is the site of our most fundamental questions about being alive. I mean this both materially and metaphysically. Those veins of the earth hold, and reshape, memory.

AA: Can you take us through the evolution of WCL from chapbook (or maybe even pre-chapbook) to full length? What has grown in your thinking and/or in the poems throughout this journey?

PH: I thought for a while that the we contain landscapes chapbook was a separate project from my first book, initially titled Anchor Baby. Prior to the chapbook was a tiny minichap project that Ross White at Bull City printed a lovely very limited edition run of in 2019. I could only seem to write in fragments back then—I refused the sentence, punctuation, the “I.” That distrust of the lyric “I,” a reckoning with it, can be worthwhile. But for me, it was also a kind of self-censorship. Was it also a distrust of myself? I started writing into that. We Contain Landscapes engages with those questions, including the idea of self-deceit—the ways a person can attempt to hide parts of themselves away, and the cost of that.

AA: I’m interested in the speaker of WCL’s fraught relationship with beauty. While the speaker revels in wonder at the beauty and pleasure that she witnesses in her body, the natural world, and her friends & lovers, she is also distrustful of it. In “Recurring,” you write, “beauty exists with no regard for goodness or the living, / and if I’m inside, even if I cannot see that weather, / I can feel it, eroding the floorboards, disintegrating / reason, ceaseless. It has an appetite,” and you’ve also explored the connection between beauty as regime and immigrant daughterhood in more depth in your essay “Unlearning My Immigrant Mother’s Ideas of Beauty” for Catapult. Could you speak to how you pursue beauty through language & devotion in your poems while also remaining critical of the ways that beauty has been used as a tool of discipline and subjugation?

PH: There’s a passage in Mahmoud Darwish’s long poem “Mural,” translated by Berger and Hammami, that reads: “Beauty takes me to the beautiful / and I love your love, freed from itself and its signs.”

Whether I like it or not, I’m a romantic and a lover. I am moved by the sensuous, by beauty. I am drawn to texture, color, and shape, and am suspicious of my relationship to the visual, to beauty that remains surface-level. But beauty, much like the poet’s understanding of the image, is not just visual but felt. Even mirage alone is indicative of desire. Despite desire’s deceptions, or perhaps our mistranslations of it, it is a life force. Like many writers, I surrender to that force, am endlessly moved and troubled by it. What one finds beautiful can be the source of our deepest pleasures and even self-knowledge. Of course, that can also be a mere product of our conditioning, what we’ve been disciplined into. I do not claim to be free of all kinds of troubling influences, including heteronormativity’s boring expectations—the limits unimaginatively drawn around our lives. The idea of beauty can be, as you articulate, a regime, weaponized as a mechanism of control, subjugation, the thoughtless consumerism that wreaks havoc on our planet.

As suspicious as I am of beauty, including lyric poetry and its limits, I relish the music of language. I need beauty to survive. And I believe in the beauty that touches all senses, and reaches beyond—for that part of us poets have been writing toward for centuries.

AA: Something I admire about your poetry is how it resists the didactic and avoids neat conclusions and overdetermined endings. The speaker of WCL reaches, searches, questions, but rarely seems to find answers. How do you see the connections between poetry, questioning, and discovery? Does poetry help you find answers, as a reader or as a writer?

PH: I’ve lived long enough to be wrong many times. Poetry is capacious enough for that.

AA: In addition to being a poet, you are also a dancer and performance artist. This gives you a particular attention to embodiment that feels present throughout the book but especially in “On Chronic Conditions,” where you write “It wasn’t just that I knew the names of body parts—I spoke to them. / I said things I can’t explain.” How does that attunement to your body & embodiment that you developed as a dancer show up in your poems? How do you view the relationship between dance and poetry?

PH: Dance was one of my first loves, and dance and poetry are modes of inquiry I cannot exhaust. At their best, both art forms offer ways of moving through, looking at, and engaging with the world that center question-asking and curiosity. Being curious about our own thoughts and bodies as sites of learning and unlearning takes ongoing practice. It also takes time. In this era of shortcuts and the illusion of urgency for the sake of maximizing profit—at costs we cannot yet fully measure, costs I’m not sure can be overstated—art demands practice and attention of us.

To feel and think deeply are practices that can hurt us. It’s part of why I insist this work is relational—we need each other.

Attunement to one’s body, though, can be painful—just as attuning to one’s thinking can be. To feel and think deeply are practices that can hurt us. It’s part of why I insist this work is relational—we need each other. I love to learn alongside others willing to put up with my experiments in writing & movement workshops I teach. Documenting more of my embodied experiments is something I’m working on in the coming seasons, as well as writing about dance.

AA: In 2021, you had a column in The Rumpus titled “Before the First Book: A Roundtable Discussion,” where you interviewed different emerging poets about their creative dreams and first book projects. Now that your first book is entering the world, I wanted to ask you one of the questions that you asked in those interviews: Is there an idea about being a writer/artist that you used to believe and have come to let go of? Or, is there an idea about being a writer/artist you’ve come to believe more strongly? Specifically, through the process of making and publishing We Contain Landscapes.

PH: It was a delight interviewing poets for that series years back, all of whom now have books out in the world or forthcoming! The process of making We Contain Landscapes deepened my love of revision and the idea that writing is a collaboration with time. A younger me was impatient, even sometimes arrogant, about this, demanding my poems be “done” sooner. But poems refuse to be disciplined! If we are lucky, they write us.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.