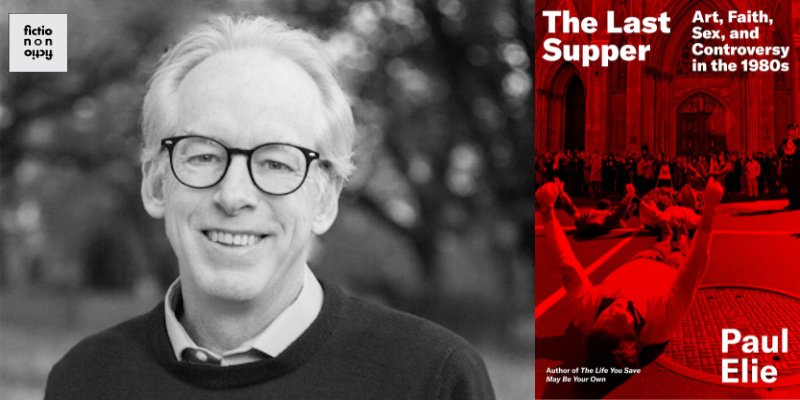

Nonfiction writer Paul Elie joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his new book The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s and Pope Leo XIV. Elie compares the new pope to John Paul II, whose conservative views shaped the 1980s. He explains how and why ’80s artists like Andy Warhol, U2, and Bob Dylan produced art he considers “crypto-religious,” a term coined by poet Czesław Miłosz. He analyzes limbo and purgatory in the work of writers of the period, including Louise Erdrich and Toni Morrison, and recalls the culture wars, including iconic incidents like Sinéad O’Connor tearing up the pope’s picture on Saturday Night Live, as well as the controversy over Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ. He reads from The Last Supper.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/. This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, and Hunter Murray.

Selected Readings:

The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s • Reinventing Bach: The Search for Transcendence in Sound • The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage • The Down-to-Earth Pope: Pope Francis Has Died at Eighty-eight | The New Yorker

Others

Madame Bovary • Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose • Love Medicine • The Handmaid’s Tale • Striving Towards Being: The Letters of Thomas Merton and Czeslaw Milosz • U2 – Gloria • “The Controversial Saturday Night Live Performance That Made Sinéad O’Connor an Icon,” Time Magazine, July 26, 2023

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH PAUL ELIE

V.V. Ganeshananthan: So for the Catholic illiterate among us, like Whitney, what was Vatican II and what was Pope John Paul’s relationship to that document?

Paul Elie: The Vatican II was a council that took place across four years that produced a series of documents rearticulating the sense of the Church and its role in the world in light of modernity. My grand uncle, Bishop Robert F Joyce of Burlington, took part in the Second Vatican Council. So it was a big part of my family’s life, and I imagine it was a big part of the early life of the new pope too, because it was all over the news weeklies and the newspapers from ‘62 to ‘65. So, the question following the Council was just how much had it made an accommodation with modernity? And different theologians and cardinals took different positions on this. John Paul who, as Wojtyła from Krakow, had been a participant in the Council, not so long afterward, began to feel that the Council had gone too far and was being misinterpreted, that the spirit of the council was being invoked in ways that trumped the letter of the very carefully worded Council documents. He joined a party that began to push back strongly against a progressive interpretation of the Council, and to argue, rather, for one that called for an authoritative interpretation of the Council. Then, when he became Pope, he used the bully pulpit, that is the papacy, to really enshrine that strong clampdown on an excessive extension of the Council throughout the church.

Whitney Terrell: In what ways was Vatican II thought to be more progressive than the previous ways the church had taught? This helps us set up for this later discussion, because I think it’s helpful to have these sort of signposts as we talk about moving through this period in the 80s, because Pope John Paul, as you say, pushed back against this quite a bit, and was much more conservative, if I’m using the right terms.

PE: It pervades the story that I tell in my book, the attempts to work out the Second Vatican Council in people’s everyday lives. The Church used to require people to ask permission to read certain books like Madame Bovary. That practice was suspended. Catholics weren’t to go into other houses of worship—

WT: Wait, I’m gonna come back to Madame Bovary. It seems like a good idea. What was the church doing? Was it trying to make sure people understood that it was a bad idea to have affairs? What was the purpose of reading Madame Bovary?

PE: I’m not really sure. I know it’s because Flannery O’Connor wrote to a priest she knew, asking for permission to read Madame Bovary when it was on the index. I don’t know what their grievance with it was, but there were dozens of works, movies, books, etcetera, that you weren’t supposed to look at if you were a Catholic. That ended with the Second Vatican Council. In sex too, the old rules still applied and were reiterated endlessly, but in the West especially, a certain amount of trust was placed on the individual Catholic to search things out according to his or her own conscience. Whether it was culture, sexuality or the fact that Catholics were now mingling in the wider world rather than staying in tightly knit neighborhoods, often defined by ethnic loyalty, all these things meant that there was an openness in Catholic culture that there hadn’t been for a couple of 100 years, and the effects of that were felt in the 60s and the 70s, and were still being felt in the 80s.

WT: To connect us back to the beginning of this, where does Pope Leo, our new pope, and the Catholic Church in general now, all these years after Vatican II and then John Paul’s more conservative rule, stand on that continuum?

PE: It’s hard to know for sure. He’s just getting started, and he, unlike a lot of people in his position, hasn’t left a vast paper trail of documents stating his positions and everything. In his early speeches, he strongly affirmed the Second Vatican Council in a positive way, and in particular, he’s affirmed an aspect of it that has been given fresh emphasis by Pope Francis, which is called synodality. It’s a technical term which, in the broad sense, has meant that a greater number of people should have a role in the life of the Church when it comes to decision making, and that it shouldn’t just be the Pope and the Cardinals. That was an imperative of Vatican II that’s been carried out, fitfully over the past half century. So he’s for synodality, he’s for Vatican II, and he has strongly affirmed a wish to carry forward the openness of the church under Pope Francis.

VVG: In the prologue to your book, you reference Sinead O’Connor’s famous 1992 Saturday Night Live appearance. She tore up a photo of Pope John Paul II. And you say that between ‘79 and that moment in 1992 “figures in what we call popular culture engaged in questions of faith and art and the ways they fit together with an intensity rarely seen before or since.” So, what caused that to happen, and when did you first identify that as a pattern that you wanted to write about?

PE: I grew up in that period. I was born in 1965; I moved to New York City to go to Jesuit University, Fordham in ‘83. A lot of material in the book I encountered firsthand, even though it’s not written in the first person. But when did I start thinking about it as material? It was after the publication of my first book, The Life You Save May Be Your Own, in 2003. That book’s about four American Catholic writers from the middle of the century: Dorothy Day, Walker Percy, Flannery O’Connor, and Thomas Merton. As I did events in connection with that book, there were two questions. One is, what kind of Catholic was I? And the other was, where are the successors to those great American Catholic writers?

I began to feel that it was a category mistake. People were looking, and maybe I was looking, for direct successors or inheritors of that really robust mid-century Catholic literary culture. Instead, I gradually came to think that in the period following, a different kind of energy was being felt. You had people raised religious, kind of emancipated from former religion by the 60s, by fame, by success, but who retained a passion for religion and a keen sense of identifying themselves as religious, which they worked out on the margins where religion met popular culture in the period that I treat in the book, roughly from ’79 to ’92.

WT: I grew up during the same time, Paul, so there are so many cultural references in this book that I really enjoy, which has been a lot of fun. I remember, by the way, my parents, who were Evangelical Christian, bringing the first Christian Dylan album to me as like, “See, you could listen to this instead of Van Halen.” No, thank you. I will not do that.

But anyway, you also use a term called crypto-religious which I’m going to now steal and use for the rest of my life to describe how artists from Andy Warhol to Bob Dylan are engaging religious thought and religious iconography during this time. I wonder if you could define that term for us and talk about how it applies to somebody like Warhol.

PE: The term comes from the Lithuanian poet Czeslaw Milosz, who used it in an exchange of letters with Thomas Merton, the monk, in the late ’50s. When I began to think of applying it to this period, I had to really figure out, in a narrative sense, what do I mean when I say crypto religious? For me as a writer, to define one’s terms is a profound act, the big figuring out that’s involved there. So crypto religious art, as I put it in the book, is work that incorporates religious words and images and motifs but expresses something other than conventional belief. It’s work that raises the question of what the person who made it believes. The question of what it means to believe is crucial to the work’s effect. As you see it, the work, hear it, read it, listen to it, then you wind up reflecting on your own beliefs.

WT: I also wanted to ask you about a term that seems related to this, the Vatican II concept that the ordinary is the site of the extraordinary, that different way of thinking about religion or Catholicism, a broadening out of finding the extraordinary. Is that connected to this? How does that move into Warhol’s work, specifically?

PE: Andy Warhol, who was raised a Byzantine Catholic in Pittsburgh and then moved to New York after going to the Carnegie Institute of Art, his conviction, established relatively early in his career, coming from advertising, was that the imagery of Post War America was full of presence. And he used that term, which is a Catholic term, in the sense that Catholics describe the Eucharist as the Real Presence of the Eucharist, that Christ is really present in the mass. Warhol saw presence everywhere. You didn’t think that you needed to kind of add meaning to a Coke bottle or have an inscrutable work like that of the abstract expressionists. The images themselves were so full of presence, in his view, that the ordinary just was extraordinary and in a complicated way, but one that I hope emerges clearly in the story that I tell, that became an aesthetic for a whole generation of post-Vatican II crypto religious folks.

VVG: So fascinating. I was raised Hindu, and would identify myself as a Hindu atheist, which I’m told I’m allowed to do. My family is Sri Lankan Tamil from Northern Sri Lanka, where there were Christian Catholic missionaries. And there’s this really interesting affinity that I’ve always seen between Hinduism and Catholicism. Also, just over the course of my life, I’ve been friends with a lot of lapsed Catholics. I’m sort of curious about the relationship between crypto religion, as you’re defining it, and being a lapsed Catholic, which is sometimes how folks are identifying themselves, in the way, almost, that I just identified myself as the Hindu. They identify culturally very strongly as Catholic but their spirituality is not in the same place. And that notion of presence that also is kind of Hindu in an interesting way. There’s a lot of porosity between these communities where my parents come from. I’m curious about how those ideas might fit, if at all.

PE: How the sense of the ordinary is extraordinary fits in with Hinduism is probably another conversation. I want to look into that. But I wrote this book partly out of a dissatisfaction with a category like lapsed Catholic. A lot of people use it, but it owes its origin to the time half a century ago where people had so much religion stuffed into them by the time they were 12 and were confirmed, that then they could spend the rest of their lives lapsing or falling away from it. That was true for a lot of the older artists in the book, Martin Scorsese, very thick Catholic childhood, for example. But many of the figures in the book belong to this slightly later period in the 80s, where you picked up some religion as you went along. So the idea that you once had it all and then fell away from it is less applicable to my own generation than it was to the baby boom generation and the wartime generation. That’s why I’m trying to use this term crypto religious instead. I think that religious instincts, they do die, but they die hard. Many of the people drawn to the work that I described, the songs of U2 and the Smiths, and the novels of Toni Morrison, are drawn to it, partly because of that sense of a real but porous border, border crossing religiosity.

VVG: Yeah, I appreciate the definition. Lapsed Catholic friends who listen to this podcast, you want to pick up Paul’s book. Interestingly, I often find that when I like a band, and then I look up who they are, I’m like, “Oh, they’re Christian.” This brings me to U2. Unbelievably, we’ve never talked about U2 on this podcast before, so I’m not going to miss the chance now. You point to them as a source of crypto religious devotion and say that Bono marked the spot where many of us still find ourselves, “religion has let us down, but religious yearning is still there stronger than we might expect.” I noticed that you shift into first person plural there. Is this something that you felt during that era, or maybe feel now?

PE: Absolutely. I grew up in upstate New York, in Albany, which had a really vibrant music scene, because it’s the town that bands stopped in the day before they went to New York or the day after they went to New York. Everybody passed through, including U2, who played their third American gig in Albany on the Boy Tour, then played a second time at a local nightclub on the October Tour. In the video for Gloria, The Edge is wearing a t-shirt from our local nightclub, JB Scott’s. When we saw this video endlessly, it was something to take such pride in that Albany was represented in one of the great rock videos of the period.

Then they played SUNY Albany, a spring weekend show. Their fame had really exploded between when they booked the gig and when they played the gig. I was in high school, but I went, stood in the front, $8 tickets, $3 plastic cups of beer, and there was Bono 20 feet away, climbing the lighting rig with that giant flag pole with a white flag on it. The flag that, to me, is one of the emblems of crypto religiosity. He’s expressing a devotion, but to what he’s devoted is indeterminate, and for people to figure out. That’s what bugged a lot of people about U2 in the punk scene that I associated with. He was just so exposed and so full of yearning with no negativity, he wasn’t calling for an end to this or that war, supporting the Sandinistas like The Clash, it was much more general, and that made him very vulnerable. But to me, that made him and U2, very attractive. And yes, he did, I did feel that he spoke for me.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Paul Elie by Holger Thoss.