The first time I ever spoke to award-winning New Zealand writer Pip Adam was over Zoom. It was 2022, right after my partner and I had signed on to publish The New Animals in the US. The New Animals is a beautifully intense novel, angry, occasionally violent—in a review, Joy Williams calls it “a strange, remorseless, powerful book, leaving the reader drained, angry, and frightened.” Sounds about right, and we wondered what Pip would be like in person. In person Pip is one of the kindest, warmest, most enthusiastic people I’ve ever met. It’s interesting how sometimes you can meet a writer and not be able to predict who or how they might be on the page, or you read their work first and then are somehow surprised by who you meet in the flesh. What is the relationship between a writer’s “personality” and the page? In fact, Pip talks about this very thing in what follows…but it’s not why we’re here.

Article continues after advertisement

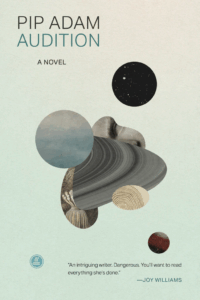

We’re here because this month Coffee House Press is bringing out the U.S. edition of Pip’s “boundless and mythic” novel Audition. In the book, Audition is the name of a spaceship, and on the ship are three giants: Alba, Stanley, and Drew. The sounds the three of them make are what keeps the spaceship moving—so they talk and talk—and if they fall silent, they grow, which, it turns out, poses a serious problem. If you’re thinking this sounds a little bonkers, you’re absolutely right. A starred review at Kirkus calls the book “Brilliantly weird. Weirdly brilliant.” I’m delighted that U.S. readers now have more of Pip’s weird (angry, warm, intense, kind) brilliance to read.

–Danielle Dutton

*

Danielle Dutton: I recently brought a class your short story “Zero Hours” alongside part of a conversation you had on your podcast, “Better Off Read,” in which you spoke about your writing’s relationship to the political. You explained that “Zero Hours,” from 2015, marked a turning point where you shifted away from “ambiguity” in your work You said: “I remember thinking, The time for ambiguity is over. And I remember one very clear question replacing this, How didactic can I get and still be writing fiction?”

I’m attracted by the way breaking the rules is often the way to write a successful genre piece of work.

I’m so interested in this question, Pip! Could you say more about this turn toward the didactic, maybe starting with what you mean by “didactic” and what you want the didactic to do?

Pip Adam: I’m going to try and answer this question without looking up a definition of “didactic,” which is quite scary for me. I did not stay long at high school and came to university as an adult so I often feel quite vulnerable talking about words because often I have made up my own definition for them. “Didactic” is a word I came across in my studies of literature. It was a term of disparagement. I heard it used to describe a certain type of directness and sentimentality. It suggested a writer who perhaps “cared too much” or maybe didn’t have the craft to hide their opinion. It was often used to talk about the work of beginning writers. It was something to be avoided. Very early on I started hearing that Emily Dickinson quote “Tell all the truth but tell it slant.” I internalized this—a good writer doesn’t let people know what they really think—and I think this is easy to see in my first collection of short stories, which are quite detached, the authorial point of view is hidden under mood and tone and clever words. I’m not disowning that work, I just can see it. All these things I was trying to be in my writing are the opposite of who I am as a person. I’m angry and raging and talk too much. I find it really hard to hide what I’m thinking. I had a friend at work once who said, “You need to fix your face.” They were referring to the fact that my disdain shows very clearly on my face.

Also, I recently heard the comedian Stewart Lee talking about irony in the comedy of the 1980s. When you could say something really shocking but you could assume your audience would understand it was not your point of view. And I think that was also part of that “the time for ambiguity is over” thought. I think we find ourselves now in a time where many hideous people have hidden in plain sight behind this assumption of irony. I’m thinking especially about Russell Brand and Louis CK.

At the moment I wrote “Zero Hours” we had a government which was making life worse and worse for anyone who wasn’t a wealthy landowner. I think all these things just made me think, “Realistically, I’m not making a commercial product but I do have a platform and why am I not using this platform to speak plainly against the things I think are cruel.”

I think this plays out in The New Animals, which is a book very much about class and work, and Audition, which is a book that has as its thesis: “Is there a better way to deal with crime than our present system?” Both these books are far more sentimental than that first collection of short stories. I’m much more open about my politics in them. I am possibly more “in them.” I think a lot about something the writer Jordy Rosenberg said in a workshop I was in once: “A novel can have a thesis just as an essay can, but a novel is not so interested in definitively answering that question.” I think the two novels, all my work, still have a degree of ambiguity in them. I still want there to be space for the reader to bring themselves to the work. Also, part of my politics is ambiguity, which I think of as “the multiple.” The ability to see that maybe my way is not the only way.

DD: I’m curious to hear what it means to you—or how it might mean differently—to have your books published at home in New Zealand versus anywhere else in the world. And then, too, how you think about the New Zealand that appears in your fiction. In The New Animals, you bring us into an Auckland that feels very alive and tangible, yet it isn’t presented as a place that needs explanation. Much as with Joyce’s Dublin, we’re dropped into its complexities and expected to keep up. Did you at any point imagine yourself writing a version of Auckland for readers beyond NZ’s borders? How important is the local or the global to your sense of yourself as a person and a writer?

PA: I’m very much a person who has been formed by American culture. My grandfather, who I never met, is Mexican-American, so there is this strange “missing part” which I think I have always tried to fill. Also, I’m very much a person who was raised by television. I didn’t always like reading but I love TV and films. The books I did love as a kid were S.E. Hinton’s books. I remember asking my grandmother to take the sleeves off one of my sweatshirts so I could look like a “greaser.” When I started reading, it was American writers. So, in a weird way, my books being published over there feels like a sort of homecoming for them.

Publishing in Aotearoa is different for sure. It feels like a family affair. There are so many amazing people around me who support me and whose work I’m so inspired by. Also, because I’m Pākeha/Tangata Tiriti (part of the colonizing population) there is a degree of responsibility when I take up space in publishing here.

There’s something attractive for me about America being this distant place—like I can maintain my fantasy of America. A place with imagined readers who all get what I’m trying to do. Whereas here I’m often face-to-face with readers. I was visiting a high school a few weeks ago and a teacher told me about how frustrating they found my book. I’m starting to realize I have this deep misunderstanding of my work. I think I have underestimated the extent to which it makes people uncomfortable. To me my books reflect the reality I live in but, yeah, I have found out over the years that maybe my reality doesn’t match everyone’s reality.

In The New Animals I was really interested in the local. I was thinking about crime books. About something like the work of Stieg Larsson, how his work is unapologetically local. The first part of The New Animals takes place in 24 hours and I made a plan and walked the novel over a 24-hour period. Many of the things that take place in the book took place on the day I walked the book. So, I was also very interested in the present moment or the near past. The past of living memory. To me it’s a very contained novel. It unfolds in real-time so I never thought about stopping that unfolding to explain anything about Tāmaki Makaurau. I was thinking a lot about 2666 by Roberto Bolaño. I know he is writing about a far more well-known place, but I liked the way the setting is revealed in the telling of the story.

DD: The New Animals starts out on that single day you’re talking about and presents as this multi-perspective, sort of Virginia Woolf-y brand of realism before (as one of my brilliant grad students put it) “exceeding realism” for the final third of the book, which also leaves the city behind. So we start in one place and genre, then we swap both for another place and genre. I read that you modeled this structure off a novel by Janet Frame, but I was hoping you could talk about what attracted you to it, and how a move like this felt important?

Also, am I right in thinking you’d call Audition science fiction (which is what some reviewers have called that final third of The New Animals)? What’s your relationship to science fiction, Pip?

PA: When I studied Art History at university, I became captured by the idea of the DADA. The energy that is formed when you put two unrelated objects next to each other. When I was in film school, I read David Mamet’s On Directing Film where he talks about the film being written “in the cut,” that empty space between one scene and the next. Then I saw Jane Campion a few years ago and she talked about an approach of “writing the next interesting thing.” What all these things have in common is this idea of a story being told not through progression but disruption. I’m really interested in what we can tell “between.” I often think I’m making rather than writing. The first draft is always hard for me but once I have “material” I can arrange it. This is how I think of genre. I’m really attracted by the rules of genre. Especially, I’m attracted by the way breaking the rules is often the way to write a successful genre piece of work. Take crime fiction. I always feel like crime fiction is fighting against its conventions. Like most crime fiction I like is satisfying because it breaks some of the rules of the genre.

The thing I like about speculative and especially science fiction is the ability to imagine outside the current power structures.

Someone said to me the other day that the reason people find my work uncomfortable or unsatisfying is because it won’t settle into a genre and I think this might be true. Just like sticking a fish next to a ladder in a DADA work gives it energy, I think sticking a Rom-Com into a work that has elements of Science Fiction and is didactically about prison abolition does something energetic to it. Someone at the high school asked me what my favorite emotion was and I said, “Awkward.” I’m not sure awkward is an emotion but it is where I live and it is what I want to write. Discomfort. Unsettled. Uncanny. I’m interested in a narrative arc that moves in these energies. I’m always asking everyone who will listen: What is the container that holds a book? Like what is story? How do we know when it is whole? I’m always fighting against the three acts and conflict and all those things, but I’m also acutely aware that I need some of these things. When I ran into trouble with Audition I used the structure of Rom-Com to put it into a shape that I could work with as a novel.

The smart and interesting people I met when I went to university in my twenties all read science fiction. It was introduced to me as a genre of incredible political and radical potential. At first I found it hard to read. I’m a very literal person. I found it hard to be in someone else’s imagination. I had to work quite hard to “get” science fiction. It was really worth it. The most radical and interesting ideas I have today come from science fiction—Samuel R. Delaney, Stanisław Lem, Ursula K. Le Guin, Octavia Butler. It is an amazing genre. I feel a bit nervous calling anything I write science fiction because I don’t think I’m a good enough science fiction writer to call my work that. The thing I like about speculative and especially science fiction is the ability to imagine outside the current power structures. I like what Kim Stanley Robertson says, that science fiction, rather than being predictive, has the ability to “capture the feeling of the present that we’re in, the sense of possibility and rapid change.”

DD: On that note: in the past few years the world has received your wonderfully strange spaceship novel, Audition, as well as Samantha Harvey’s Orbital and Sofia Samatar’s fascinating novella The Practice, the Horizon, and the Chain. There are probably others I’m forgetting right now…but do you think there’s something about this particular historical moment that lends itself to experimental spaceship novels?

PA: I think there’s lots of factors. I think the way technology allows us to open our mind to space travel. Samantha Harvey talks about watching the live feed from the space station. Also, the obsession of the richest people with space flight. The way it’s such a strong metaphor for the divide between rich and poor. The end of this planet makes us think about what’s next. And the pandemic—a spacecraft feels quite a lot like a home during lockdown.

One spaceship novel I love and was incredibly inspiring to me, like it made room in a lot of ways for what I was trying to do, was Olga Ravn’s The Employees. I can’t recommend it highly enough. It is such an amazing work, writing back, in many ways, to Lea Gulditte Hestelund’s sculptures. Also, there is an exciting new work by Una Cruickshank, a writer from Aotearoa, called The Chthonic Cycle—it’s incredible. In many ways it deals with our current situation by placing it in the long history of Earth. There is this provocative quote from it that has made me reevaluate all my writing about spacecrafts:

“The notion that they [the rich] will take us with them to live on Mars or put us to work at a business park in orbit, is a boring person’s fantasy. Whatever happens next, you and I will see it out here, in the only place with trees and liquid oceans, the only place where we can breathe and stand upright. The work to save what is left, to pull out of a threatened ecological death spiral, will be done—like always—by countless little hands.”

__________________________________

Audition by Pip Adam is available from Coffee House Press.