Now Winter Nights …

Now winter nights enlarge

The number of their hours;

And clouds their storms discharge

Upon the airy towers.

Now let the chimneys blaze

And cups o’erflow with wine,

Let well-tuned words amaze

With harmony divine.

Now yellow waxen lights

Shall wait on honey love

While youthful revels, masques and courtly sights,

Sleep’s leaden spells remove.

This time doth well dispense

With lovers’ long discourse;

Much speech hath some defence,

Though beauty no remorse.

All do not all things well;

Some measures comely tread;

Some knotted riddles tell

Some poems smoothly read.

The summer hath his joys,

And winter his delights;

Though love and all his pleasures are but toys,

They shorten tedious nights.

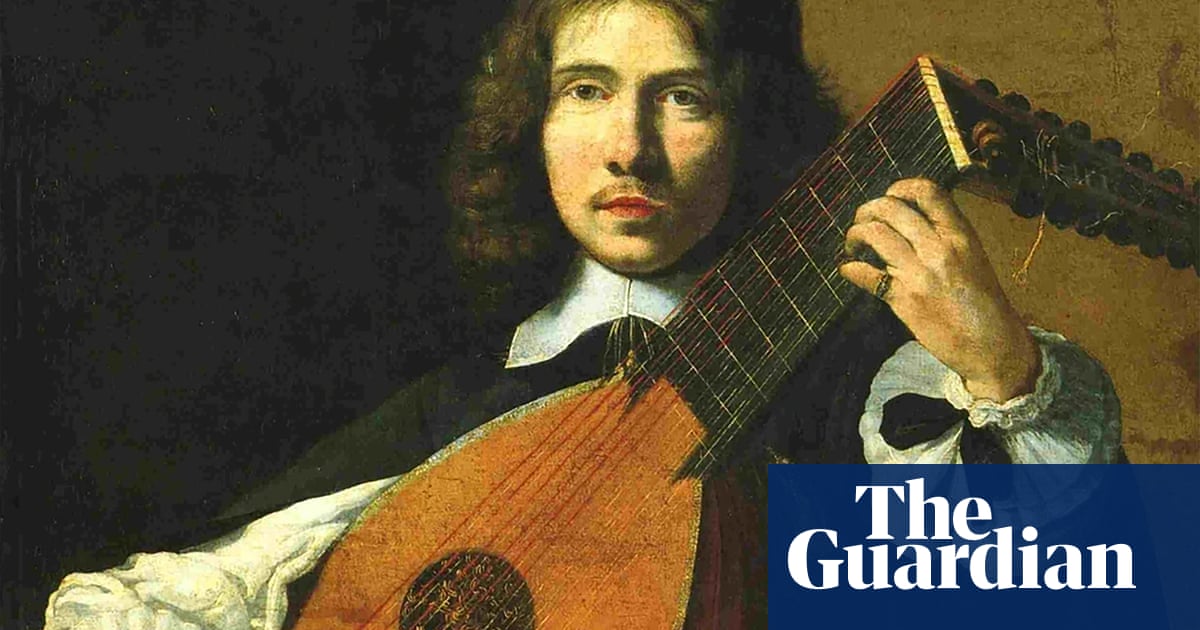

Thomas Campion (1567-1620), poet, composer and physician, became an ardent Classicist while studying at Cambridge, although he left without taking a degree. Poem of the week previously looked at one of his translations of Catullus. This week the poem is his own song, Now Winter Nights …, from The Third Book of Ayres.

Campion’s lyrics never feel shallow on the page. This one sings the consolations of winter with typical grace and precision, with some interestingly mixed feelings adding tension. The poet is a sensuous conjuror of atmosphere, but he’s not only that: he argues with himself, and thinks the argument through. Stock rhymes are used unobtrusively and intelligently, finding a context that refreshes the nuances, even of old favourites such as “love/remove” and “joys/toys”. Less familiar rhymes nicely “enlarge” the discourse they “discharge”.

Iambic trimeter is the poem’s dominant rhythm, allowing a light but firm “step” appropriate to the themes. But in each verse, the penultimate line claims more space. I think the effect of this shift to iambic pentameter is perhaps explained in the opening of the poem: “Now winter nights enlarge / The number of their hours …” Campion expands his allowance of “number” to demonstrate metrically those longer nights, and the endless possibilities of amusement.

Darkness, storms, tedium establish contrast with the constant blaze of cultivated domestic pleasures. The company – clearly familiar to Campion – is safe inside the “airy towers” it inhabits: Campion referred to his songs as “Ayres” so we can hear a faintly punning echo in his choice of a somewhat understated winter adjective, “airy”. Indoors, no doubt, airs composed by the poet of “well-tuned words” and “harmony divine” feature importantly in the home-spun entertainment, and perhaps help obscure the wailing of the storm.

Both verses condense three quatrains, rhyming ABAB. This alternation lets the three-beat line find a little extra space for the working out of a metaphorical figure, as when, at the end of verse one, a kind of surrogate summer emerges from winter, the “yellow, waxen lights” almost turning into bees as they “wait on honey love”. Candlelight can of course aid the appreciation of beauty. Readers might feel a love poem is trying to hijack Campion’s artistic reticence here.

Lovers’ discourse is undeniably essential to the fabric of the winter evenings. Notice the different meaning of “dispense / With” in the opening lines of the second verse, the positive rather than the negative inference that the season is conducive to long talks, wrangles and, of course, the endlessly fascinating drama of sexual rejection. (“Much speech hath some defence / Though beauty no remorse.”)

As for the recitations, dancing, riddle-telling, Campion drily sounds a warning that “All do not all things well”. Some of the performers are fine – but only some. As his art reveals, Campion is something of a perfectionist. And so the admission that, although useful for passing the time, “love and all his pleasures are but toys” doesn’t seem either a surprising or unearned conclusion. While the poem moves beautifully and its construction never feels as if it required hard work, Campion shows that keeping the long winter nights pleasurably occupied can overstretch resources. In verse two, the “tedious nights” are consistently at the door.

While praising Campion for his rhyming skills, it’s worth remembering that he notoriously begins his treatise, Observations in the Art of English Poesie, with a forthright criticism of “ear-pleasing” rhymes that are “without art”, and laments that “the facility and popularity of Rime creates as many Poets as a hot summer flies”. There still seems to be some uncertainty among critics as to whether Campion simply disliked rhyme that was poorly handled, or disliked it altogether.

I suspect he enjoyed practising it but that, in theory, he was ambitious for poetry to have a wider intellectual scope. Additionally it seems he’s criticising English imprecision in scansion in much of his book rather than failures of rhyme. He investigates syllable stress with a keen ear, and produces numerous illustrations of the various prosodic terms (the iamb, the trochee, and so on). Excellent examples of his own non-rhyming work are woven through the Observations.

One of them, the beautiful lyric Rose-cheeked Laura, has entered the canon, but Campion’s unrhymed verses are too often overlooked. I’ve picked out another poem featuring “Laura”, less well-known, but very worth quoting. Rhyme would certainly spoil the pace and the mental footwork, the moral twists and turns, of this self-mocking run of trochaic dimeters:

Follow, follow,

Though with mischief.

Armed like whirlwind

Now she flies thee;

Time can conquer

Love’s unkindness;

Love can alter

Time’s disgraces:

Till death faint not

Then, but follow.

Could I catch that

Nimble traitor

Scornful Laura,

Swift-foot Laura,

Soon then would I

Seek avengement.

What’s th’avengement?

Ev’n submissly

Prostrate then to

Beg for mercy.

Campion’s Observations in the Art of English Poesie can be read here and his musical setting of Now Winter Nights Enlarge enjoyed here.