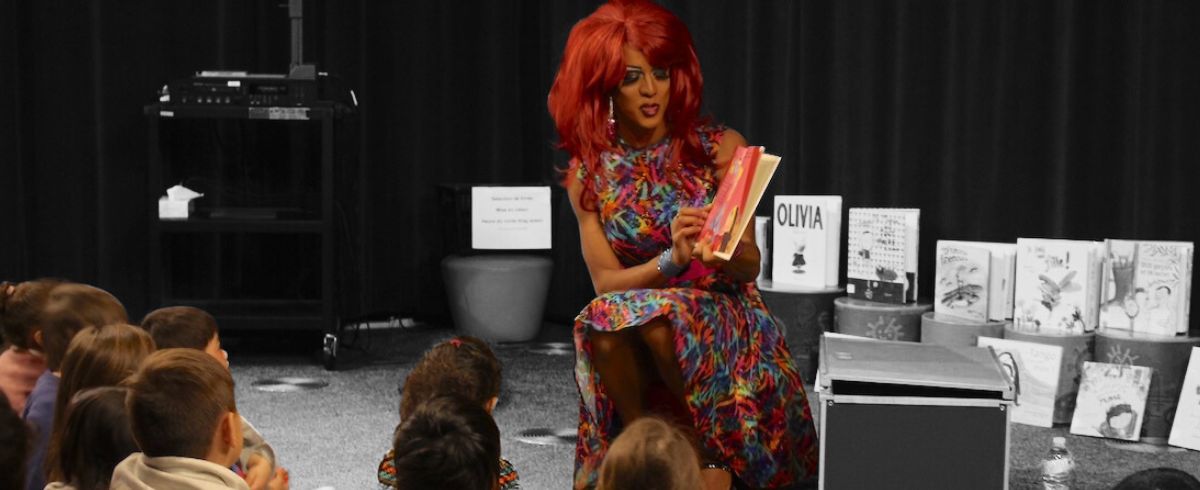

More than one hundred children and adults walked through metal detectors and past bomb-sniffing dogs to attend Drag Queen Story Hour at a community church in northeastern Ohio in December 2022. Drag Queen Story Hour began in San Francisco in 2015 as an effort to encourage literacy and provide children with queer role models. Libraries and bookstores across the United States began to host the story hours, some of which drew many times the usual number of people who typically came to library events. But protests against it also grew more frequent.

Article continues after advertisement

The Ohio church’s pastor, Jess Peacock, had fielded “accusations of pedophilia, grooming, and horrible things being done to kids” in the days leading up to the December 2022 story hour. Violent threats prompted her to spend $20,000 on security measures.

Just the day before the story hour, federal authorities arrested Aimenn D. Penny, a neo-Nazi, for attempting to “burn…the entire church to the ground” with Molotov cocktails. Penny told authorities that he had targeted the church “to protect children and stop the drag show event.” Penny belonged to “White Lives Matter, Ohio” and had distributed white nationalist literature.

Peacock’s fears were well-founded: on the night of March 25, 2023, about a week before the church was scheduled to host a drag show and another drag story hour, Penny hit the church with Molotov cocktails in a failed attempt to set it on fire. (The shows went on as planned, and in January 2024, Penny received an eighteen-year sentence in federal prison.)

Anti-LGBTQ protests in the name of child protection have flared up across the country. Also in December 2022, New York City Council member Erik Bottcher filmed anti-drag protesters outside of a public library in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, an area known for its substantial LGBTQ community.

No evidence supports the assertion that drag queens or queer people more generally are uniquely dangerous threats to children.

One man held up a sign that said “Stop Grooming Kids for Sex” and asked Bottcher if he was a member of “NAMBLA,” the largely defunct North American Man/Boy Love Association, whose stated aim was to legitimize relationships between older men and much younger ones. A woman raised her own smart phone to film Bottcher as he filmed her. She flung expletives at him and asked, “What are you, a pedophile?”

Far too many children and adolescents in the United States face very real sexual danger. Starting in the 1990s, and steadily ever since, new revelations have surfaced about the extent of clerical sex abuse in the Roman Catholic Church, with diocesan leaders hiding accusations of pedophile priests and placing tens of thousands of children, of all genders, in harm’s way. Similar scandals have rocked the Southern Baptist Convention, the Boy Scouts of America, and other civic and religious organizations.

No evidence supports the assertion that drag queens or queer people more generally are uniquely dangerous threats to children. Scholars who research hate crimes argue that not only are people in sexual or gender minorities not more likely to perpetrate sex crimes, but they are far more likely to be the victims of assault, harassment, and bullying.

The allegation that homosexuality endangers children is an old one, taking shape initially in the 1910s and 1920s when vice squads arrested men for having sex with minors. As we have seen, campaigns in the 1930s against the “sexual psychopath” circulated warnings about predatory queer people who lured unsuspecting adolescent boys into their criminal perversions.

Using nearly the same logic, Florida’s legislature systematically investigated and fired lesbian and gay public school teachers and university professors in the 1950s and 1960s. An unsuccessful 1978 effort in California known as the Briggs Initiative, inspired by Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign in Miami-Dade County, would have allowed school districts to fire anyone “advocating, imposing, encouraging or promoting” homosexuality. Anti-gay statutes defined queer people as criminals, and many mental health professionals continued to treat homosexuality as a psychological disorder.

These damaging stereotypes affected the ability of queer people to retain their parental rights. Judges and juries construed the simple fact of being queer as a disqualification for safe parenting.

In an infamous case from California in 1967, Ellen Nadler’s petition for custody of her child was denied based on what the judge described as her “psychological problems.” Only if Nadler agreed to psychiatric treatment for her lesbianism, the judge determined, would she be permitted unsupervised visits with her child. Lesbian mothers from New York City to Portland, Oregon, contributed to legal defense funds.

The Daughters of Bilitis created a legal resource center for lesbians worried about losing custody of their children. Del Martin, one of the group’s founders, had given up custody of her only child when she and her husband divorced in the 1940s, feeling immense shame about her sexual desires for women and hopeless about her chances of winning a favorable decision in family court. The lesbian and gay rights movement of the 1970s hoped to shift those attitudes.

Even so, many queer people stayed closeted within unhappy heterosexual marriages for fear of losing custody of their children or went through excruciating legal ordeals to try to remain part of their children’s lives. In the decades before the Supreme Court issued its decision in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), formally recognizing same-sex marriage equality, advocates for queer partners, parents, and children first had to convince the courts—and the broader public—that queer people conformed to, rather than undermined, the conventionally understood American family.

Family court judges stood in the way of queer parents’ rights. For decades, they ruled that LGBT people were unsuitable parents. Relying on a medical definition of queer sexuality as pathological and contagious, judges warned that the presence in the home of a loving same-sex relationship put children at risk of sexual harm.

That logic ultimately denied Sharon Bottoms custody of the son she bore during a brief marriage to a man, more than twenty years after Ellen Nadler’s unsuccessful custody petition. Bottoms had started to date women in 1991, when her son was still very young. She soon formed an intimate partnership with April Wade. Bottoms and Wade could not marry legally, nor could Wade adopt the boy under Virginia law.

A custody battle with Bottoms’s ex-husband resulted in the court terminating her parental rights and placing the child in the custody of his paternal grandmother. The judge decided that, by kissing and hugging in front of the child, Bottoms and Wade had endangered the child’s safety, as if their display of affection was a noxious gas contaminating innocent lungs.

The persistent belief that homosexuality was a kind of contagion inspired conservatives to compare LGBT anti-discrimination laws to sexual indoctrination. An unsuccessful 1992 ballot initiative in Oregon, for instance, would have made it illegal to use state, regional, or local funds to “promote, encourage, or facilitate homosexuality.” (The lesbian feminist attorney and activist Nan D. Hunter wryly nicknamed this legislative agenda “No Promo Homo.”)

The idea that gay men and lesbians “recruited” children to become homosexuals mirrored the anti-porn movement’s notions that sexually explicit words and images could cause violent behavior. Both campaigns likewise characterized sexual desires as forces that required vigilant supervision.

Granting even the most basic antidiscrimination protections to LGBT Americans was controversial. The same year that Oregon’s initiative failed, Colorado adopted a constitutional amendment that made it illegal for local governments or the state to ban discrimination against gay men and lesbians.

With clear echoes of earlier arguments against civil rights for Black Americans, the amendment’s supporters derided the LGBT equality movement as a plea for “special rights” that disadvantaged straight people. Taken together, these arguments warned that queer people were sex deviants intent on pushing heterosexuals to the margins of American life.

These anti-LGBTQ measures coincided with headline-grabbing child abductions in the late 1970s and 1980s, which in turn spawned a new era of child safety advocacy. Reports of child abductions and assaults had not increased demonstrably, but sensationalist news coverage gave the appearance of an escalating crisis. By the middle of the 1980s, innumerable cardboard milk cartons for sale in the United States featured a photograph of one of these “missing children.” Television networks launched programs devoted to cracking cold cases.

While not all these cases involved evidence of sexual assault, fears of sexually deviant criminals fueled a widening panic over “stranger danger” and child abuse. The overwhelming majority of child sex abuse was still committed—as it had been for centuries—by family members and acquaintances, not strangers.

Conservatives blamed the apparent rise in sexual crimes against children on feminism, gay rights, and the expansion of sexual freedoms during the previous decades. The anti-tax, pro-military right won support from religious traditionalists by making “family values” a cornerstone of the emerging Republican coalition. As President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Missing Children’s Act of 1982, he and his allies argued that sexual liberation had created a culture that encouraged child abuse.

Arguments against the sexual revolution associated it with other left-leaning causes, grouping Black nationalist and antiwar protesters with feminists and gay liberationists as stokers of social chaos. Sexual conservatism once again served the interests of white privilege.

Vocal supporters of the Missing Children’s Act sought more funding for the juvenile justice system, which disproportionately affected nonwhite children, and argued for longer sentences for convicted minors. As in the past, these measures to restrict gay and lesbian rights brought more police into nonwhite communities; both populations, conservatives argued, posed threats to public safety.

In the 1990s, amid a wave of unfounded allegations of abuse and even Satanism at daycare centers and preschools, a related panic spread myths about sex-education curricula that allegedly encouraged students to strip naked and explore one another’s bodies, as if Betty Dodson herself was standing in front of kindergarteners with a Hitachi Magic Wand. Opponents argued for “abstinence-only” curricula instead, and such plans received government support in the 2000s.

Concerns about sex education in the public schools helped motivate many previously apolitical people, and married women with children in particular, to get involved and even run for school board and other public offices.

Concerns about sex education in the public schools helped motivate many previously apolitical people, and married women with children in particular, to get involved and even run for school board and other public offices. The prevalence of porn on the internet convinced these activists that all sexual content damaged their children.

Child sex abuse became something of a national obsession. In 2004, MSNBC debuted To Catch a Predator, a show in which reporters and private investigators used entrapment to ensnare men who solicited sex from minors. Its formula mimicked the aims and methods of earlier anti-vice crusades: Anthony Comstock sent decoy letters to abortionists, and police on the vice patrol went undercover to entrap men interested in sex with other men.

On To Catch a Predator, men in an extralegal group called “Perverted Justice” impersonated young and almost always white girls in online chat rooms, luring adult men to a house where camera crews (and sometimes, but not always, actual police officers) intercepted them. The show, which ran until 2007, led to the arrests of three hundred men.

Anti-drag protesters in the 2020s speak of perverse dangers. Drag, they claim, is a form of pornography that attempts to lure unsuspecting children into a life of gender and sexual deviance. Multiple surveys of trans youth meanwhile demonstrate a connection between anti-trans rhetoric and incidences of self-harm and suicidality. LGBTQ+ advocates insist that while drag does not harm young people, efforts to impede LGBTQ+ people’s rights and freedoms do.

This politicized national preoccupation with child sex abuse has upended the unrelated provision of medical care to transgender youth. Advocates for and recipients of gender-affirming care (GAC) describe it as life-saving, especially for young people struggling through adolescence.

GAC is a catchall term for medical and nonmedical interventions for transgender people who wish to socially and/or physically transition their gender. Supporting a person’s adoption of pronouns or clothing appropriate for their gender; psychological counseling; and medical services such as endocrinological or surgical care all fall under the GAC umbrella. Transgender young people may be prescribed hormone therapies to pause the progression of puberty (puberty blockers) or, later in adolescence, hormone-replacement therapies to encourage the development of the secondary sex characteristics common to their gender identity.

Adult patients can seek operations such as “top” surgery to reduce or augment breast tissue or “bottom” surgery to remove or reconstruct internal or external genitals. Hospitals very rarely provide surgical GAC to legal minors, despite what anti-trans activists claim.

Of the thousands of bills introduced in state legislatures during 2023, nearly 550 targeted transgender people, whether to limit access to GAC, ban trans athletes from school sports, or prohibit schools from using a student’s preferred pronouns. By the end of 2023, twenty-three states had restricted or outlawed GAC care for minors, and several others tried, unsuccessfully, to ban drag performances on the premise that drag was a pornographic violation of children’s safety.

Civil libertarian and LGBTQ+ legal advocacy groups challenged all these measures as unconstitutional infringements on sex equality, but as of this writing, state legislatures continue to debate additional restrictions on GAC, athletics participation, and social affirmation.

The letter of these laws reveal their authors’ intention: the imposition of distinct male/female gender differences and exclusive heterosexuality on the entire U.S. population. Laws limiting GAC for minors include carve-outs for intersex infants and children, referred to in these bills as “children with a medically verifiable disorder of sex development” or “DSD.” (Intersex activists have long rejected the language of “disorder” as pejorative.)

“Intersex” is a general term for any person with a “difference of sexual development,” whether due to chromosomal, anatomical, or gonadal anomalies, some of which result in atypical genital development. The category encompasses androgen insensitivity syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Klinefelter syndrome (XXY), Turner syndrome (XO), and Rokitansky syndrome (a body that is XX but at birth lacks a uterus and/or a cervix), among other conditions.

Intersex advocates and major medical associations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, argue strenuously against any nonconsensual genital surgeries unless they are medically necessary. The presence of an enlarged clitoris or a micro-penis, they argue, does not constitute a medical emergency in a child, who should be allowed to make their own decisions, in adulthood, about any possible surgical alterations to their genitals.

Bills targeting trans minors ignore that nuance, instead suggesting that while GAC for transgender minors is abusive, surgical interventions on the genitals of otherwise healthy intersex infants is a healthcare priority. These policies reflect not medical best practices but a political vision that seeks to legislate a binary concept of gender and sex.

Proposed bans on GAC and drag are often accompanied by efforts to restrict discussions of sex and sexuality in schools and to eliminate books with LGBTQ+ themes from public and school libraries. For centuries, people have spoken out against such restrictions, whether through lectures, newspaper editorials, or information shared via radio, television, video, or the internet. Opponents of reform have often thus turned to censorship, branding anything they consider offensive as “obscenity.”

Censorship is about stopping communication. As both supporters and opponents of LGBTQ+ rights understand, communication allows for connection. But whereas anti-gay and anti-trans activists see information related to gender and sexuality as a form of contagion, advocates for queer people’s rights recognize the value of opportunities to affirm or clarify previously inchoate desires.

Historical evidence supports only one of these interpretations. Opponents of LGBTQ+ rights deny that sexuality and gender nonconformity have histories at all because recognition of a past populated by gender-nonconforming people, non-scandalous expressions of queer desire, and multiple (rather than homogenous) ideas about sexual morality would undermine their cause entirely.

Could younger Americans take sex back from the naysayers and fearmongers? In a 2012 issue of The Atlantic, reporter Hanna Rosin wrote admiringly about young American women who had embraced casual sex, or “hook-up culture,” and used it for their own ends. Unbothered by pornography or crass humor, these women recognized their value in a sexual marketplace and took advantage of opportunities to have the kinds of sex they wanted, when they wanted it, all without any apparent desire for long-term commitments at that stage of their lives.

Contrary to reports lamenting the dangers that girls and young women faced in this new sexual frontier, Rosin remarked that “for college girls these days, an overly serious suitor fills the same role an accidental pregnancy did in the nineteenth century: a danger to be avoided at all costs, lest it get in the way of a promising future.” I would amend Rosin’s timeline, because fears of plan-derailing pregnancies persisted well into the twentieth century, but I otherwise find her statement striking: young American women who want to enjoy sex and pursue their educations and careers have decided that casual sex is far preferable to a committed relationship.

That said, this casual sexual culture has not translated to equitable sexual pleasure; men experienced orgasm during hook-ups at nearly twice the rate of women. Men and women describing shared sexual encounters also came away with different understandings of what had occurred, with men reporting that their female partners had orgasms at two to three times the rate of the women’s self-report of orgasm. Nor did Rosin’s relatively sunny picture of commitment-free heterosexual sex account for a growing awareness of pervasive sexual harassment, assault, and “rape culture.”

Far from a hedonist hook-up bonanza, since the 1990s Americans have been living through what sociologists have called a “sex recession.” Several studies from the early 2000s and 2010s found that about one-fifth of college seniors had not engaged in any form of sexual intercourse, and that only about forty percent of “hooking-up” events included sexual intercourse. Teens and adults are having less sex, with fewer partners across their lifetimes, and with fewer sexual encounters each year.

Another Atlantic story, this one in 2018, captured a sense of dismay about these changes. Although a steady decline in the U.S. teen pregnancy rate might appear to be “an unambiguously good thing,” there was reason to fear that “the delay in teen sex may have been the first indication of a broader withdrawal from physical intimacy that extends well into adulthood.”

The causes of the American sex recession appear manifold, and it mirrors trends in Japan, Sweden, and the Netherlands. Americans in 2018 were masturbating more often than they had in the 1990s, often while consuming video or internet pornography. Teens and college students were less likely to be in committed relationships, but they were not having all that much casual sex compared to prior generations. Some young women were avoiding hook-ups because of past experiences with or fear of being pressured by their male peers to engage in rough sex acts that the men had seen in pornography, especially anal sex and choking.

As people become more isolated and fixated on solitary pleasures, the opportunities to meet potential partners face-to-face have apparently declined. Dating apps hardly substitute for in-person sociability because they so heavily favor physical appearance over other traits.

Particularly as the #MeToo movement exposed the pervasiveness of coercion in Americans’ sexual experiences, many observers concluded that the future of sex looked grim. Scholar Asa Seresin coined the term “heteropessimism” to characterize the gloom that had descended over heterosexuality by the late 2010s. Many young people either viewed heterosexuality as a pathetic concession to normative expectations, or they surveyed the cascade of evidence of men’s abuses of women and concluded that such relationships could never incorporate respect, desire, and fulfillment.

One manifestation of heteropessimism, Seresin notes, is the “incel” movement: virginal men who justify hatred of or even violence against women who refuse their advances. In this light, the sex recession may not simply be the result of many people making a calculated decision to delay sexual initiation but a hostile landscape in which heterosexuality, at least, appears pathetic, impossible, or obsolete.

Is the situation really so dismal? Perhaps we might consider younger people’s hesitation to initiate sex, amid a profusion of information about sexuality, as a hopeful sign. Better prepared than many previous generations to understand both the mechanics and the possible consequences of sexual intimacy, they are making decisions on their own timelines.

A movement for “pleasure activism,” rooted in Black queer/women’s liberation politics, offers another pathway, one that connects sexuality to social justice. Pleasure activists honor the words of the poet Audre Lorde, a Black lesbian and feminist who wrote in the early 1980s about “the erotic as a resource…that can provide energy for change.” They seek to empower themselves and their communities through a recognition of their sexualities.

As I write this paragraph in early 2024, “ethical non-monogamy” has burst into mainstream news coverage, which vacillates from outrage to titillation. Proponents reject what they view as the oppressive trappings of traditional sexuality, while critics point to the persistence of jealousy, gender inequality, and unexamined class privilege in some of the most widely circulated narratives of nonmonogamous relationships.

The practice of polyamory is not, of course, new. It has long been well established within many queer communities, flourished in Betty Dodson’s countercultural social circles, and might well describe Complex Marriage at Oneida.

In the early 2000s, groups like the National Coalition for Sexual Freedom and the more niche Unitarian Universalists for Responsible Multi-Partnering began to host conferences and offer resources for people exploring “romantic love with more than one person, honestly, ethically, and with full knowledge and consent of all involved.” The practice’s actual popularity is difficult to gauge; most of the renewed attention to polyamory highlights a cohort of affluent and mostly white heterosexuals pursuing personal fulfillment.

If we find ourselves struggling to understand the erotic fantasies or fears of a rising generation, we should think historically.

These seemingly contradictory trends—toward erotic liberation or sexual avoidance—expose the limitations of trying to treat sexuality as a static force in our lives. Instead, if we find ourselves struggling to understand the erotic fantasies or fears of a rising generation, we should think historically.

We should recall the myriad moments in this book’s narrative when broad currents of social change—regarding enslavement, women’s rights, obscenity, religion, social justice, policing, and so on—enabled or foreclosed sexual conduct. We might then acknowledge the salience of sexual identities (today, more manifold than ever), even as we recall how differently people in the past described their genders, desires, and relationships.

This history does not point toward liberation, however much some of us might wish that it did. Never could I have imagined that my long-scheduled plan to spend June 2022 writing a chapter about the battle over legal abortion would coincide with Roe’s demise. American politics today reverberates with debates over abortion access, GAC, and the alleged obscenity of books about queer teens. And I am confident that whenever it is that you are reading this book, sex will be no less relevant to the political arguments that affect your freedoms.

But if the history recounted in this book is any guide, both individual identities and collective activism will continue to shape the possibilities for sexual pleasures—and the manifold meanings of those fierce desires—for the foreseeable future. History is at the heart of Americans’ arguments about sex; resolutions to many of these issues depend on whether we deny or affirm that history’s existence.

______________________________

Fierce Desires: A New History of Sex and Sexuality in America by Rebecca L. Davis is available via Norton.