First published in 1979, Rosalind Belben’s Dreaming of Dead People is a seductively strange novel, leap-frogging between folkloric pageantry and the disappointments of real life. Lavinia, its narrator and central character, is thirty-six, in the “middle of life,” and alone. On a visit to Torcello, an island near Venice—that watery, carnivalesque city—her thoughts become self-reflective. What follows is a meditation on upheaval and the shifting understandings of the self that come with aging, with travel, and with erotic love. In Belben’s writing, time periods dissolve: the phenomenon of the medieval pageant is invoked; Robin Hood becomes a character; dreams are recorded; and desires rise up, then settle down.

Over three weeks this summer, I corresponded with Belben via email about the process of writing Dreaming of Dead People, and how it feels for it to be reissued forty-six years after its original publication by the British publisher, And Other Stories. Belben—who, after a nomadic lifetime, now lives again in Dorset, England, where she was born—was a delightful interviewee, her answers swift and vivid. Toward the end of our interview, good news broke: more of her intricate and wryly-funny novels will soon be reissued by both And Other Stories and NYRB. It was a heartening development, and a signal that in life—like in Belben’s novels—time needn’t always be linear: the past can return to us again.

Rhian Sasseen: I want to begin with a general query into how you approached writing this book. What inspired you? And since you’ve mentioned feeling that the novel might be dated—do you see this book innately tied to the time in which you wrote it?

Rosalind Belben: At the time, I remember being struck by the freedom allowed painters and artists to stare at the human body, warts and all. Writers of fiction, on the other hand, seemed to have to keep within the bounds of taste and decency. Women writers—well, those especially: by 1977, Portnoy had been masturbating with raw liver for almost a decade.

I wanted Dreaming of Dead People to seem considered, the opposite of stream-of-consciousness. I had a very clear idea of what would go into each chapter. I visualized the arrangement of these chapters to echo the compartments of a biography. It seemed to me in those days that readers obtained a frisson from the confessional, from the sensation of fastening their teeth on the author’s leg. The resulting fiction was in truth a tease. In part, at any rate.

And whether or not it’s dated? The gaudily coloured vibrators of today were not around. The logistics were different. It was possible to function with a different mindset—and the voice of that character, unfamiliar to me now, seems to me naive and youthful. I don’t suppose I could have written it at any other juncture.

RS: Sexuality, particularly female sexuality and desire, is important to the book, most obviously in the second section, “The Act of Darkness,” when Lavinia reflects on her sexual history. There’s a great line that made me laugh, “Female orgasm involves intangibles.” That line follows a paragraph about reading—there’s quite a bit of wordplay in this section. Do you see a tie between language and sexuality for Lavinia? And for you as a writer?

RB: I’d forgotten that line. I was more into wordplay and punning then than at any time since. Here, I was laughing too—but as one laughs at the absurd, the scandalous that isn’t so terrible after all. The Limit—which I wrote four years earlier—had been full of puns. Back then I was crying. Most of those puns passed me by when I was going back through it in 2023 ahead of republication by New York Review Books. I no longer saw them.

In 1977, I had been tutoring some classes and needed to stop. Instead, I had taken on a ghosting job that required me to research, interview for, and write a full-length non-fiction book within four months. I’d managed to do that. I was raw from a misunderstanding with close friends, a couple. I was glad to hide myself away.

Histrionically, I named the narrator after Lavinia in Titus Andronicus—to whom far worse happened. Like me, Shakespearian. I’d been to a gory Royal Shakespeare Company production at the Aldwych Theatre in London.

From this distance, I can see I indeed assemble the components of a life. Sexuality for sure, and visual images, dreams, the habit of reading, the centrality of animals in her life as in mine, guilt, sorrows and deep grief, the barriers between Lavinia and other people…and the chemistry. There is a kind of indivisibility. I don’t separate language—so long as it’s my language, my grossness, my embellishment—from living, or living from libido. I wouldn’t want to. Looking back though, I might deplore the diction that shows off with a posed lyricism. That is dated.

In those days readers obtained a frisson from the confessional, from the sensation of fastening their teeth on the author’s leg.

To be reductive: is making a pun sexually exciting…? Is wordplay foreplay, so to speak. I don’t know. I’m neutral there. I wonder! A male author of my acquaintance used to claim to sit at his desk writing with an erection. A different analogy might be to imagery. The brain sparks a pun as it would a metaphor, and too much metaphor, as with a pun too many, is a doubtful pleasure?

RS: A Titus Andronicus reference certainly lends a sense of drama to the character! Have theater and the performing arts influenced your fiction?

RB: Painting and sculpture were what I was looking at. When I first returned to London after a long spell in the country, I could drive my little car into the West End and find a parking place—no meters yet—and most visual art was free. I visited galleries assiduously. I was hungry. But of course I could also park outside theatres. It was a brief, blissful time when one paid little for theatre tickets, life seemed to be arranged around a very moderate purse. The masks of Cuckoo and Owl that cast their aura over the novel were first seen by me in an RSC production of Love’s Labour’s Lost. The medieval poems, which stand in place of illustrations in the novel, were as vital. They probably led back to The Erotic World of Faerie by Maureen Duffy—from that book, I arrived at the cul-de-sac of the Robin Hood ballads. Such details are like notes in the margin. They don’t affect the trajectory.

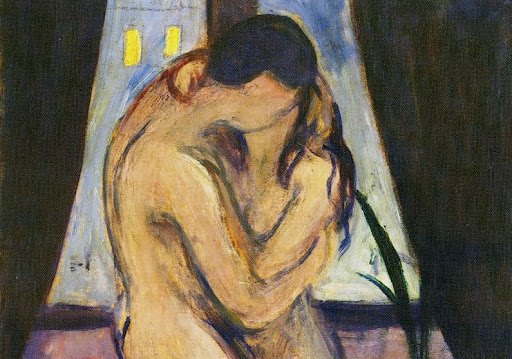

Modern art, however, seemed more central. In the first chapter, ‘At Torcello’, Lavinia speaks of Edvard Munch’s “The Kiss”:

“In the work of Edvard Munch, the jealous, the anguished, the lonely, the subjective expressionist, it is he who is the more visible, though invisible, the more felt, his is the presence. The faces in The Kiss are not blurred by their loving but by the bitter green mind of an artist who would love to kiss.”

I took my own words there as a kind of template. I wrote them in all innocence. Only later did I find that Munch had been involved in an affair. Yet, that discovery didn’t invalidate the emotions I had perceived. One can be jealous, anguished, lonely: there is no self-deception. Merely a duality, a paradox, at the heart of things.

RS: Age is a fraught topic for Lavinia, who approaches her own age—36—with a sense of foreboding and refers to herself as an old maid. Do you think this anxiety surrounding women’s aging has changed at all since Dreaming of Dead People’s initial publication?

RB: I don’t know. It goes without saying that the internet has brought new pressures. After the war—WW2—it was demographic: a generation of women was left without spouses and sweethearts. They populated the staffroom of my boarding-school. Their anxiety could have communicated itself to me. Their strain, their dwindling life chances, permeated the walls.

Anxious or not about aging, I do think women are kinder to each other these days.

As for Lavinia, hyperbole isn’t foreign to her, let’s say. The entire work—her monologue—could be seen as a preposterous exaggeration. Old maid is a term of abuse, or has been. Plainly, she is not a maid in the strict sense. But she is so cut off from what other women might feel and think. It’s part of her problem. Lavinia doesn’t seem to have been born with a natural understanding of what I might call the Umwelt of women. I expect I share that with her. Besides, is her anxiety genuine? She asserts on page 179 that she will “step defiantly on to false teeth, grey hair, reading glasses, vaginal atrophy, and varicose veins.” She is ahead of herself, I’d suggest, because she sees no future in between. There is a little voice in her that is crying ‘not enough, not enough’.

Readers at the time, after dividing between those who were stirred (plenty of men among those) and those who were disgusted (plenty of women among those), expected another novel in a similar vein. It didn’t cross my mind to repeat myself. This—hubris, perhaps—was to cost me dear. The how I’m saying it has always mattered more to me than the what I’m saying.

RS: Your playfulness in regard to the many meanings a word might have extends to temporality in the novel, too—there are multiple time periods in the book, often switching between chapters. How did you approach writing the past?

RB: I planned to keep quiet about it, but I shall have to confess that I haven’t read Dreaming of Dead People since 1989. I must take it on trust, as a piece in aspic. Not self-preservation so much as common sense—I knew if I read it again I’d have a fit. I wouldn’t want to see it re-issued and I’d have missed out on it as a pretty new volume.

The chapters can’t have a linear progression from one to the other. They are ordered by subject-matter. It seems natural. I could say that we are in the ‘now’ of the narration from which time fans out. The main thing was to make sure the text was allocated to the right chapter, and that each chapter kept to its individual topic. There is a hidden structure whereby the chapters ‘Cuckoo’ and ‘Owl’ form a centre plank whilst two chapters at each end make the trestles.

If one is eliding and slithering through half a life, there are bound to be jumps. It’s better not to be too conscious of the technical challenges when writing. I may have tackled them instinctively. On the whole, despite what I’ve been saying, I am not a writer who knows what she’s doing: I find out afterwards.

As to writing the past, I keep to the past that is in my locker. I go back to circa 1900. My mother was born in 1908. Her memory—very vivid—coupled with mine is about as far as I can “remember.” If she hadn’t mythologized her childhood for me, I doubt I could have imagined characters alive in those days or had the confidence to let them talk to each other.

Is making a pun sexually exciting…? Is wordplay foreplay, so to speak. I wonder!

RS: On a more procedural note, what was the actual writing process of Dreaming of Dead People like, compared to your other books? Did it come quickly or slowly, or were there difficulties or surprises?

RB: I used to write by hand in spiral notebooks. That could be rather fraught. About twenty years on, in 1996, I changed to a computer keyboard. The new temptation was to rattle away, so I had to learn to curb prolixity.

The writing of Dreaming of Dead People came as a relief. I was able to turn to it straight from my previous industry. I can’t pretend that, by then, after my first flush of innocence in the publishing world, I wasn’t susceptible to sudden crushing disappointment and upsets, so I sealed myself off as much as I could. I happened to live in a splendid location, on the third floor, with a sunny view over a large part of London, and woods nearby to walk in. My handwriting had a habit of getting smaller and smaller.

RS: From the novel’s title to its ending section, dreams and a “dream-life,” as Lavinia refers to it, are frequently invoked. What is the role of dreams and dreaming in your work and your writing process?

RB: I have a theory that invented dreams don’t work in fiction. Not in mine, at any rate. I always commandeer dreams of my own. This goes for male characters as well as female. So the man in Hound Music has one of “my” recurring dreams in the opening pages—that he has left an animal forgotten in a back paddock. For many years, I’d dream that I had left an animal with no water, or with the ice not broken, or without feed, and everlastingly I would dream that I’d forgotten to shut up the hens at night. I still do that, yet I last kept poultry in 1969. Often the hens are not even my own hens, and I am stricken with guilt. On the whole I like my dreams and can “read” them with utter clarity.

There is a darkness in Dreaming of Dead People—a dark hole represented by the chapter “Owl.” Into it, I am painfully aware, Lavinia stuffs all her mishaps and failings, her sins of omission and ignorance, and lines them up to be—in a manner of speaking—shot at.

This novel and the next, Is Beauty Good, have elicited some touching confidences. Women tell me about their orgasms, and men tell me about taking a beloved dog to the vet to be put down. About the deaths of adored dogs. What is more rare nowadays is the reader who will talk to me about birds or flowers.

RS: Lastly—it’s been a pleasure writing back and forth to you these last few weeks and getting a peek inside your head. Is there anything else you’d like to cover about Dreaming Of Dead People or any of your other works that you feel we haven’t touched on?

RB: I mentioned that Dreaming of Dead People raised expectations that I could turn out more of the same. I was baffled when its first publisher rejected—with some disgust—the next novel he commissioned. I destroyed it decades ago with no regrets. The lesson was that semen was welcome, blood was not. Blood gave him hysterics. Titillation good, first aid bad. In other words, a child’s nosebleed was an unsuitable subject. I’ve been wary ever since.

And I’ve always had difficulty with the apparently human desire of readers—I count myself among them—for characters to be redeemed or, better, to redeem themselves. The Edwardian children’s books inherited from my mother had a moral message and I bought into that. As a grownup I grew sceptical. I used my own grandmother as a model for one character. She remained horrid all her life. Yet, I was coaxed into “redeeming” that character, to give readers a degree of satisfaction, regardless of what really happens. Doing that troubled me very much.

Related

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.