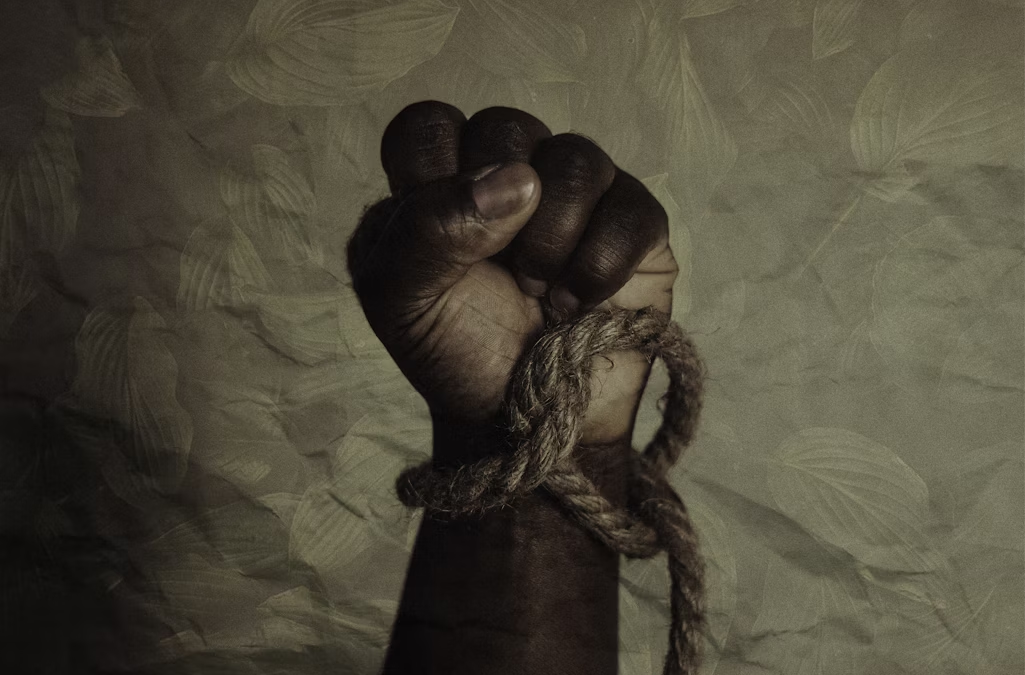

When the 20th-century Black intellectual and organizer W. E. B. Du Bois set out to rescue the Reconstruction era from the slander it had suffered, he felt the weight of the historical baggage confronting him. Across more than 700 pages of lush prose-poetry that composed Black Reconstruction in America (1935), Du Bois rewrote the story. He centered the agency of the recently emancipated – the Black men and women who threw off the “chains of a thousand years.”

Twenty-first-century historians have vindicated Du Bois’s take, with recent studies exploring Reconstruction as the nation’s second founding and a testimony of Black survival amid the campaign of white terror that ultimately ended the experiment in multiracial democracy. Yet Du Bois, who also wrote fiction, has found fewer followers among contemporary American novelists, who have more often trod the imaginative terrain of the run-up to the Civil War rather than its long aftermath. Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Beloved (1987) represents an exception: even as we think of it as a story about slavery, the novel actually takes place in Reconstruction.

In the work of Nathan Harris, the 33-year-old Chicago-based writer with an MFA from the Michener Center at the University of Texas, that literary landscape is beginning to shift. His Booker Prize-longlisted debut The Sweetness of Water (2021), told the tale of recently emancipated brothers, Prentiss and Landry, as they imagine a world for themselves amid a Reconstruction Georgia occupied by US troops, hostile white Southerners, and the husband and wife pair who befriend the siblings. Amity, Harris’s sophomore novel, out this month, chronicles the relationship of brother and sister Coleman and June, who are legally free but must traverse boundaries and borders both personal and political to realize that freedom, reclaim their relationship, and construct a world for themselves without any guarantees of legal rights or protection.

Last month, I interviewed Harris via a shared Google Doc. It certainly outpaced the handwritten missives that 19th-century Americans sent to one another from the battlefield to the homefront. We spoke about narrative craft and historical content, Toni Morrison’s legacy for writers of Black historical fiction, and the links between the past and present US at a moment when news reports about ICE raids and legal challenges to birthright citizenship emphasize the abiding stakes of Reconstruction today.

Gregory Laski: Amity, like The Sweetness of Water, takes place in the Reconstruction era. What made you decide to stick with this historical period for your second novel?

Nathan Harris: Honestly, I never intended to return to this period. Part of me even wanted to avoid it. The postbellum South is so steeped in horror that, during research, there were times I felt like quitting. But there are two sides to that coin, because it was also the research that kept me going, kept highlighting parts of the past that just felt captivating to me. In this instance I came across stories of Confederate loyalists who fled to Mexico after the war, hoping to recreate the lives they’d lost. It was a kind of fantasy, this belief that they could reclaim their independence and find refuge from a United States that had rejected them. Alongside them were many of their formerly enslaved people, effectively marooned in Mexico. I had never seen that story told in fiction before. I thought maybe I could shine a light on that specific window in time, in that particular place, and that it might resonate with readers. Amity is what came out of that.

GL: You’ve mentioned, in other interviews, that you’d not been exposed to much fiction set in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, and I wonder if that’s partly a function of how few contemporary novelists have grappled with the Reconstruction era?

NH: I have no idea. Maybe I’m just not seeing it! There’s so much great historical fiction being published these days, and I know I’m missing some incredible work. It’s certainly rich terrain to explore for novelists, and a very formative time in our nation’s history.

GL: Yeah, I hear you. I mean, Jayne Anne Phillips’s Night Watch (2023) is set in the 1870s, but in terms of books focused on the Black freedom struggle, I could only think of Beloved (1987) by the late, great Toni Morrison. I actually took to Bluesky to check myself, asking folks to name 21st-century novels set in Reconstruction, and a famous scholar of African American literature replied with a plot summary of a book whose title she couldn’t recall offhand. Turned out, it was The Sweetness of Water. I think that exercise confirmed my thesis! Do you have any ideas about why we don’t have more contemporary fiction set in this era?

It was a kind of fantasy, this belief that they could reclaim their independence and find refuge from a United States that had rejected them.

NH: Far be it from me to pathologize why authors might gravitate towards any time period, genre, subject. What I know is that Toni Morrison was there early on, as you said, and she made space for the rest of us. Nowadays, to our great fortune, there are an unending number of Black authors inventing their own fiction based on our collective pasts that might not be set in that particular moment in time but certainly are in conversation with it. We’re all working along the same historical continuum, and that sense of interconnectedness is what feels most powerful to me.

GL: Who are your models for writing historical fiction about this period, or historical fiction in general?

NH: There are many, but I’ll give you one to start, Edward P. Jones. My first editor, Ben George, gave me a signed copy of The Known World when my first novel was published. I couldn’t think of a better gift. He actually visited The Michener Center when I was in school and I was too terrified to take his workshop. Probably for the best; having my early work in front of him might have been a death knell before it had time to mature.

Another influence, especially on Amity, was Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. Mr. Stevens was a guiding light when I was shaping Coleman’s character. Both are dealing with repressed emotions in very fascinating ways. I can’t say I managed what Ishiguro did, not by any stretch, but that novel was a touchstone and an inspiration nonetheless.

GL: I’m curious about the creative timeline of the two novels, whose publication dates span four years. Was The Sweetness of Water already out in the world when you began what would become Amity? Or were you working on both simultaneously?

NH: My first novel took a rather slow road toward publication, and I used that time to start in on Amity. Nothing truly creative with The Sweetness of Water was taking place then. So there was definitely some overlap but it wasn’t like I was writing two novels concurrently. I’ve had other authors tell me that the best thing to do to get your mind right when you’re enduring the stress of publication is to write something fresh. The early pages of Amity were exactly that for me.

GL: In the acknowledgements to Amity, you cite a number of scholarly works on 19th-century US and Native history, calling the studies “instrumental in the writing of this novel.” How do you draw on facts from these historical sources to fuel the creation of fictional figures and worlds?

NH: I just try to immerse myself in the time period and use what I learn to enhance my work. The research shapes the language, the sense of place helps ground scenes. My novels would be impossible without the true scholars who came before me. I’m really indebted to them.

GL: You also mention that you did research at the border. Tell us about what that process looked like, and how it informed Amity’s concerns with geopolitical questions of territory and land rights, between Mexico and Texas in particular?

I’ve had other authors tell me that the best thing to do to get your mind right when you’re enduring the stress of publication is to write something fresh.

NH: I felt I needed to see the region firsthand. I had a wonderful guide who showed me around, took me on a tour of Big Bend, and shared, with me, the history of the area. It was such an intriguing melting pot, shaped by so many different indigenous tribes, settlers, nations, and shifting borders. But mostly the trip gave me the sense impressions I needed to imagine what it was like for my characters. It’s a very unique area. I can only imagine how daunting it must have been for someone encountering the desert for the first time.

GL: How did the physicality of Big Bend, and also its history, shape your portrayal of Amity as a place in the novel? As I read, I sort of had Morrison’s chronicle of all-Black towns in her brilliant novel Paradise (1997) in the back of my mind, and because you mentioned maroonage earlier, I am now thinking of it as maybe a maroon colony too.

NH: Regarding Big Bend, it was a very unique mix of tranquility – the absolute quiet at night was a sort I was not used to, having spent a great portion of my adult life in the city – alongside that daunting feeling I spoke of earlier, brought on by the epic scale of the mountains, the vastness of the desert. I could go on but suffice to say you’re hitting on exactly what I felt. That this was a place someone could escape to and find peace; a place where someone giving chase might have second thoughts.

I’ll just add that the Black Seminoles lived side by side with the Seminoles. They shared a great deal culturally and had a strong allegiance, but it was a complex social relationship that sets their communities apart from the all-Black towns I was used to reading about.

GL: When Publishers Weekly announced the deal for Amity, the book’s title was The Rose of Jericho. Both have rich symbolic meaning in the narrative, for June’s arc especially. Who made the change, and when?

NH: It was a mutual decision made fairly early on.

GL: Did you encounter Rose of Jericho, the tumbleweed that your characters call a “resurrection plant,” during your visit to Big Bend?

NH: It’s funny you ask, as I actually bought some! They sell Rose of Jericho as a souvenir around Big Bend. I still have it stored in the desk where I write. I had absolutely no idea you could bring some home with you but it’s sort of the perfect little memento of the trip and my time writing the novel.

GL: As I read Amity, I also was rereading Sweetness. What struck me was how sensitively you depict such complicated relationships between Black and white characters. In Sweetness, for example, the formerly enslaved brothers Prentiss and Landry should have little reason to desire any interaction with the white characters George and Isabelle Walker, much less to trust them – yet the story repeatedly underscores moments of “sympathy” among the cohort. As a writer, how do you craft relationships that at once recognize the historical realities that would close off routes to cross-racial alliance and reveal opportunities for unexpected openings?

NH: One reason I enjoy writing into the past is that I have these opportunities to play around with class and racial politics during very heightened moments between a diverse cast of characters. Prentiss and Landry might not desire to have interactions with George, or any white characters, but what choice do they have, really? The world they inhabit is a white one. They must navigate their newfound freedom amid the very people who once enslaved them.

I approach these relationships as I do any other. You search for the humanity in every single character, no matter how good, how evil, and relay it onto the page. As I delve further and further into the characters’ psychology, what comes to the surface is often unexpected even to me. When it’s pat, or if it feels like I am only doing what I want the character to do, as opposed to what they would do, is when the work becomes routine, and I know I need to dig deeper.

GL: Staying with questions about technique, Sweetness deploys close third-person narration spread across the book’s multiple characters. By contrast, Amity shifts to the first-person perspective of Coleman for the bulk of the chapters, but retains close third person for June’s story, which appears in intercutting sections. How did you arrive at that structure?

Prentiss and Landry might not desire to have interactions with George, or any white characters, but what choice do they have, really?

NH: The narrative dictates the requirements of the form. Coleman needed to tell his own story. There was no getting around that. To filter him through a third-person perspective would have diluted something essential about his person and something essential about his story. It didn’t feel as necessary for June, and I was able to explore her inner life with a bit of distance. The contrast also creates a dynamic element to the novel, more texture and breathability.

GL: I understood Amity as a bit of a supplement to – or maybe a refraction of – the more hopeful vision of Reconstruction that Sweetness offers, with the possibility of Black-white cooperation and economic equality. Amity trains its sights on the characters of color, especially the interiority of June and Coleman’s sibling relationship, and near the end of the novel, you write that June’s “store of sympathy” for the family that enslaved her “had gone dry.” It’s as if the two books, read together, chart various historical paths that Reconstruction might have taken – and, at least in terms of its defining ideal of interracial democracy, still might take. Does that reading resonate at all with you?

NH: I really do find it gratifying when people arrive at such articulate and thoughtful interpretations of my work! It resonates, yes, though it wasn’t something I consciously set out to do when writing Amity. Still, I love that there’s now an opportunity to consider the two novels side by side, and to see them in conversation with one another.

GL: You said in a 2022 interview that the Reconstruction era “reflects” current conflicts about race and class, and even contending ideas about “our nation.” Revisiting that statement now, and having published Amity, do you view the links between this particular American past and our present in 2025 similarly?

NH: Absolutely. If anything, those links feel even more urgent now. Which is a bit depressing. Nonetheless, authors like me keep reaching toward the past to try to make sense of the present climate. I will say there’s something grounding in it too, almost therapeutic, which is also perhaps why readers keep returning to historical fiction as well. The country endured then, with all its flaws and divisions, and somehow found its way to this moment in one piece. We have to hold on to some sense of hope, some belief that we can keep going. I think of Coleman or June on their journey, which feels endless, with so many obstacles, and yet they persist. That’s what we all must try to do. Persist in the face of so much darkness.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.