I have written lists like this before during all the years I’ve been writing and giving talks about why books and reading matter. But I do so now with increasing urgency as we are inundated by a tsunami of censorship, from book bans to assaults against the free press and school curriculums, the excising of facts and words from government websites (our websites, our history), and attacks on educators and students. These diabolical onslaughts are further weaponized by the reckless defunding of scientific and medical research and the undermining of public libraries (including the Library of Congress), museums, and other cultural institutions. These shockingly destructive actions are meant to erode intellectual and artistic freedom and dismantle our constitutional rights.

To read and advocate for books during this crisis is a small but not insignificant act of resistance. Many of us are taking refuge in books, finding succor and perspective, beauty and truth, escape and connection. In the memoirs, polemics, and conversations below, writers ardently and incisively attest to how books save and sustain them, elucidating our profound need for books and affirming the need for us to defend our right to read and write freely.

*

Glory Edim, Gather Me: A Memoir in Praise of the Books That Saved Me

(Ballentine Books)

Many of us say that books have saved us by providing perspective, companionship, and sanctuary, but the predicaments Edim needed help navigating were exceptionally difficult. The firstborn child of immigrants from Nigeria, Edim was five when her brother, Maurice, was born; she was eight when their parents divorced and her mother, a former teacher who taught a very young Edim to read, began working long shifts as a nurse, leaving Edim to care for her brother. The siblings reveled in the weekends spent with their father until he abruptly disappeared. Worse yet was her mother’s doomed second marriage which left Edim responsible for Maurice and a new baby brother. Not even college brought relief when her long-traumatized mother needed care.

From the start, Edim read hungrily, searchingly, steeping herself in “survival stories.” She found comfort in Little Women, as have so many book-loving girls and future writers, and inspiration in Mildred D. Taylor’s Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, a novel about a ten-year-old Black girl in Mississippi during the Great Depression. Edim loved both books because, like her, their young female characters “were struggling, they had burdens and responsibilities beyond their years, and they still found a way to be emotionally fulfilled. They found a way out of the danger that surrounded them.” The more demanding her life became, the more urgently and astutely Edim read, finding her way to the wisdom and artistry of Zora Neale Hurston, Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, bell hooks, Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, Audre Lorde, Jamaica Kincaid, and Toni Morrison. Ultimately her ardor for and abiding faith in literature, especially writing by Black women poets and writers, inspired her to found Well-Read Black Girl, an innovative, impactful, and award-winning nonprofit literary organization.

Dwight Garner, The Upstairs Delicatessen: On Eating, Reading, Reading about Eating, and Eating While Reading

(Picador)

New York Times book critic Garner shares his entwined passions for reading and eating, preferably performed simultaneously, in this warm, funny, unabashed, quick-footed, and erudite memoir. He begins with his formative years in West Virginia and Florida, where he rushed home after school to “gather an armload of newspapers and magazines and library books and paperback novels” and amass an equally hefty array of food, diving into it all on the living room floor. These “combined gluttonies” eventually led Garner to “keep a sentry lookout” for writers of all kinds writing about food, which, he wryly observes, “has not been among literature’s great subjects.” His avidity in collecting food references enables him to deftly combine delectable quotes, writer anecdotes, and personal experiences like a chef stirring unexpected ingredients into a savory stew.

Critic Seymour Krim coined “upper delicatessen” as a metaphor for his memory, providing the perfect title for voracious eater and reader Garner’s energetic and witty account of a typical Garner day, from breakfast to lunch, shopping, a swim or a nap, drinking, and dinner. Throughout he succinctly considers food as it relates to family, class, and culture, recounts how he became a book critic, and tells stories about his marriage to cookbook author Cree LeFavour. Garner’s consumption swings from fast food to farm-to-table, Diet Coke to martinis, while the mind-blowing array of writers he spotlights encompasses Zola, George Orwell, Jim Harrison, Albert Murray, Gary Shteyngart, Nora Ephron, Chang-rae Lee, Jhumpa Lahiri, Namwali Serpell, and many, many more. Garner leaves us bedazzled with his unique celebration of eating and the food for thought reading provides.

Peter Orner, Still No Word from You: Notes in the Margins

(Catapult)

Orner is a virtuoso of subtlety, nuance, and essence. He approaches moments, memories, and the emotions they arouse at a slant, almost surreptitiously, his tone wistful, pensive. He is also edgy and witty and sometimes furious. In both his fiction, including the ravishing short-story collection Maggie Brown & Others, and his essays, Orner mulls over his experiences growing up Jewish in Chicago and its North Shore suburbs, a milieu rife with struggle, longing, anger, secrets, lies, and love. Books are his refuge, as he asserts in Am I Alone Here? Notes on Living to Read and Reading to Live (2016) and, somewhat more covertly, Still No Word from You.

Like Garner’s reading memoir, Orner’s is loosely structured as a day in the life of a writer, but instead of pegging it to meals, he marks time, from “Morning” to “Mid-Morning,” “Noon,”“3 P.M.,” “Dusk,” and “Night.” That said, this is actually an account of a day in the mind of a writer. Musings and recollected scenes from his past morph into thoughts, for example, about a poem by Amy Clampitt, finding his mother’s penciled “Yes!” in the margin of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind, and piquant reflections on Jean Rhys, her fiction, and her “merciless concision.” Orner practices merciful distillation, infusing every word with regret, sorrow, or wonder. Absurd and poignant family stories alternate with tales about such writers as Franz Kafka, Virginia Woolf, the underappreciated Wright Morris and Maeve Brennan, Lorraine Hansberry, Bette Howland, Paul Celan, and Andre Dubus. The result is an intimate, melancholy, frank, and surprising paean to reading and books.

Elaine Castillo, How to Read Now

(Viking)

When Castillo looks back at her childhood as a first-generation American of Philippine origin in a “wide and diverse” Filipinx community in the Bay Area, she writes, “it feels like first I became a reader; then I became a person.” She credits her father with lighting the fuse: “He was making me read Plato’s Symposium when I was in middle school.” This set Castillo on a path of free-wheeling reading that led to writers of many different backgrounds, reading that carried her far beyond not only school curriculums but also the West’s white-centric reading tradition. While touring with her first novel, America Is Not the Heart, Castillo began to consider just how entrenched white supremacy is in what and how we read. This, she avows, must change. In rigorous and electrifying linked critical essays, Castillo not only astutely analyzes “the racial politics and ethics of how we read our books,” she also parses how we read history, each other, and the world.

Along the way Castillo reflects on how writers of color in a white-majority culture are expected to focus on trauma and tragedy in stories that will “primarily serve to educate, console, and productively scold a comfortable white readership.” She assails the cherished belief that reading engenders empathy and the “repugnant and paternalistic” concept of “giving voice to the voiceless.” Castillo pursues her arguments in scorching critiques of Nobel laureate and “casually fascist stylist” Peter Handke, J. K. Rowling and “mainstream white-authored fantasy narratives,” and fellow Californian Joan Didion and “settler colonial terror and anxiety.” Castillo also conducts keen analyses of films and TV shows, including Monsoon Wedding and HBO’s Watchmen. She brings the same steely interpretative powers to reading the living world, stating that it is “impossible to untangle our disastrous climate present from our disastrous colonial past.” Castillo’s revolutionary polemic is meticulously and zestfully argued, eviscerating, clarifying, and invaluable.

Azar Nafisi, Read Dangerously: The Subversive Power of Literature in Troubled Times

(Dey Street Books)

Azar Nafisi advocated for the power of fiction in her landmark memoir in books, Reading Lolita in Tehran, a bracing account of the risks she took to meet secretly with women students to read and discuss Western novels forbidden in the Islamic Republic of Iran. In The Republic of Imagination (2014), Nafisi explores the influence fiction has had on life in America, where literature is increasingly endangered. Here she extends her inquiry into the importance of books in a series of poignant letters written to her late, book-loving, courageous, and much-missed father in 2019 and 2020 as violence and oppression surged in Iran, and the U.S. suffered under the inept and corrupt Trump administration, the pandemic, and police killings, all of which catalyzed consequential protests. Once again, Nafisi, a tireless advocate for “literature as resistance,” turned to books for illumination. As she provides fresh and sharply relevant interpretations of works by Salman Rushdie, Ray Bradbury, Plato, Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison, David Grossman, Elliot Ackerman, Elias Khoury, Margaret Atwood, James Baldwin, and Ta-Nehisi Coates, she considers how tyrants come to power and how in democracies ideas are silenced by “prejudice, censorship, and slander.”

When Read Dangerously was published in 2022, Nafisi hoped we would recover from Trump’s disastrous term in office even as she perceived the insidious damage: “The establishment of some form of normalcy does not mean that these deep undercurrents of hatred have gone away and democracy is safe.” Even more presciently, she ends with a call to readers to speak out, to use our “immense” collective power. Reading this chronicle during the second, exponentially more catastrophic Trump presidency renders Nafisi’s insights and concerns all the more urgent: “every reader who is deprived of reading the books she wants; every bookstore, library, museum, or theater that closes; every book that is censored or removed from schools and libraries; every art, music, or literature program canceled in our schools and other institutions—these should all remind us of our responsibility.” Nafisi signs off with: “Readers of the World, Unite!”

Nancy Pearl and Jeff Schwager, The Writer’s Library: The Authors You Love on the Books That Changed Their Lives

(HarperOne)

“How does the practice of reading inform the life of a writer?” This question led famed librarian, critic, novelist, and book advocate Nancy Pearl and writer, playwright, editor, and producer Jeff Schwager to converse with twenty-two writers about books that have transformed them. In these lively interviews they ask each writer to name the books in their inner library, the books they “carry in their hearts and minds, . . .the books that informed their lives.” Each avid conversation among knowledgeable readers wholeheartedly dedicated to books glimmers with unexpected and revealing disclosures.

Jonathan Lethem’s bibliomania as a reader, writer, and book collector is fathoms-deep and many-tentacled. His mother guided his first forays, steering him to Ray Bradbury and Agatha Christie, and he quickly reached for many more books on her shelves, including Raymond Chandler and Dostoevsky. Laila Lalami, Luis Alberto Urrea, Maaza Mengiste, and Viet Thanh Nguyen talk about their very different youthful experiences reading across cultures, borders, and languages. T. C. Boyle didn’t “read deeply” until college when he discovered Flannery O’Connor. Madeline Miller talks about Watership Down and The Odyssey. Louise Erdrich craved Marjorie Morningstar and reveled in James Welch’s Winter in the Blood. Jennifer Egan loved Laura Ingalls Wilder’s The Little House on the Prairie books. Many of these impassioned readers become writers talk about Nancy Drew, comics, Dickens, and oodles of mysteries and science fiction. In all, these are mesmerizing, funny, affecting, and enlightening literary exchanges.

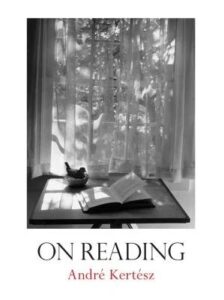

André Kertész, On Reading

(W.W. Norton)

The countless words that have been written about reading can scan as cerebral, yet we read with our entire body. We ourselves with stories and we often succumb to the spell of the page in public places. This proclivity fascinated photographer André Kertész. On Reading, a slender and elegant volume, contains sixty-six black-and-white photographs Kertész took of people engrossed in books and newspapers around the world between 1915 and 1970. First published in 1971 and reissued with gloriously lustrous duotones in 2008, this book of dynamically composed images wordlessly and resonantly celebrates the universal beguilement of reading.

We see readers basking in sun and solitude on rooftops, high and still above the bustle of city streets. In Buenos Aires in 1962, a man in a long coat reads a small book while standing before a wall bristling with angry graffiti, including two black footprints as tall as he is. In a serene scene in Venice in 1963, a man reads beneath an archway, his back against the wall, gondolas docked in the canal below. Three little raggedy boys sit in a row pressed against each other on a mound of rubble in front of a worn plastered brick wall in 1915 in Esztergom, Hungary, Kertész’s homeland. All are wearing caps, two are barefoot, and each is concentrating on a book open on the lap of the boy in the center. Kertész photographed readers in parks, libraries, classrooms, seen through a window, waiting to go on stage, on fire escapes, a balcony, a train, all with heads bowed, faces rapt with concentration. His finely composed portraits capture the there and the not-there of reading, the transfixing and transporting wonder of this profoundly human enthrallment. May we all read freely and in peace.

_________________________

Donna Seaman’s River of Books: A Life in Reading is available now from ODE Books.