Similes: there’s nothing like them. Called “quite likely the oldest readily identifiable poetic artifice in European literature” by the classicist James P. Holoka, the simile—an explicit comparison using like or as—has never gone out of style in English verse. It’s a mainstay of tuneful Romantic ditties (Robert Burns: “O my Luve is like a red, red rose”), of modernism’s jump scares (T. S. Eliot: “When the evening is spread out against the sky / Like a patient etherized upon a table”), and of contemporary poetry at its most carefree (Nikki Giovanni: “I mean…I…can fly / like a bird in the sky…”). The negated simile—X is not like Y—has its own dismissive, snarky history, ranging from Renaissance parodies (Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130: “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun”) to epochal diss tracks (Kendrick Lamar’s “Not Like Us”). Similes, I’ve sensed, are especially having a moment now, in the last decade or so of poetry. Maybe, with that like or as easing in the comparison, they’re quicker to spot than metaphors, less hyperbolic-sounding, and hence better suited to our overliteral times. Or maybe—as I’m finding while writing this paragraph—they’re just a delight (and a cinch) to quote.

Article continues after advertisement

From the looks of the spring’s new poetry books, similes are, like, everywhere in 2025. They’re in the first poem of Ashley D. Escobar’s debut book GLIB, exemplifying its titular style in a crisp quip: “Walking in New York is like scrolling the internet.” They get the last word in Benjamin Zephaniah’s Dis Poetry: Selected Poems & Lyrics, in the uncollected poem “Evolution,” disputing capitalism’s supposed advancements for Black Britons: “De situation look to me just like slavery.” In Steven Espada Dawson’s Late to the Search Party, similes draw out oddity from the ordinary: “From twenty yards away the adult megaplexxx sign / looks like a crescent moon stuck on its beetle back.” And in Taylor Portela’s Tranny Muse, similes give voice to larger-than-life aspirations: “I want to be famous like a burning library.”

Want to read whole stanzas, even poems, constructed simile by simile? Pick any of Hera Lindsay Bird’s exuberantly figurative love poems, in which every comparison giddily overshoots the one before: “Love comes back…/ like a murderer returning to the scene of the crime…”; “Love like Windows 95 / The greatest, most user-friendly Windows of them all.” For a simile on the scale of an entire book, look to Diana Arterian’s second collection Agrippina the Younger, whose title denotes the Roman empress assassinated in 59 c.e.—unless it’s Arterian herself, a woman both like and not like her, nearly two millennia later. How big can a simile get? A new anthology of Palestinian poetry, edited by George Abraham and Noor Hindi, takes its title from a line in Fargo Tbakhi’s “Palestine Is a Futurism: Prophecies (Cruising Jerusalem)”: Heaven Looks Like Us. A people, their historical place, their prophesied future: all embraced in a simile, just like that.

*

George Abraham and Noor Hindi, editors, Heaven Looks Like Us: Palestinian Poetry

(Haymarket Books)

It’s hard to imagine a better time for Heaven Looks Like Us than now—but hard, too, to explain the complexly layered sense of “now” at play in George Abraham and Noor Hindi’s anthology of Palestinian poetry from 2000 to today. First conceived in 2020, Heaven Looks Like Us is bookended by Abraham’s introduction and Hindi’s endnote, both dated early 2024, only months after the start of the ongoing war and humanitarian crisis in Gaza. Among the anthology’s innumerable virtues is its daring to think together, to consider poets across languages, generations, and places as collaborating in the unified project of a single people. Heaven Looks Like Us congregates contemporary poets working in Arabic, Danish, English, and French with poets as singular as Yusuf Ezidden Salah (1928-2016), born two decades before the onset of the Nakba, whose poems (the editors report) “come to us in the form of translations of napkin scribbles and papers inherited by his granddaughter,” and the late Heba Abu Nada, whose contribution to the anthology was written ten days before she was killed by an Israeli airstrike on October 20, 2023: “Yesterday, a star said / to the little light in my heart, / We are not just transients / passing.”

Diana Arterian, Agrippina the Younger

(Curbstone Books / Northwestern University Press)

Title: Agrippina the Younger—namely, the Roman empress who was the fourth wife of the emperor Claudius and the mother of the next emperor, Nero, who reputedly arranged her assassination. Author: Diana Arterian, the author of two poetry collections, whose author’s note is mercifully assassination-free. Those two women are the co-stars of Arterian’s latest book, which narrates the life of the former in picked-clean, gap-riddled poems with historically exacting titles (“Agrippina Becomes the First Noblewoman to Give Birth on Campaign Becomes the Elder in an Isolated Place Later Named After the Baby Future Empress Agrippina the Younger”), and catalogues the latter’s research on Agrippina in trustworthy, self-questioning prose poems: “I am here to collapse the disk of time, stand beside her. But these aren’t even all her same structures.” Agrippina the Younger can sometimes read like two projects in one, each good enough to be published solo: the Agrippina poems add up to a verse biopic, lean and lived-in; the prose poems, a travelogue featuring Arterian herself as tour guide, armchair art historian, and immaculate endnoter. But the book’s sparks fly in the flinty friction between the two projects, between verse and prose—as in a poem on the thirteen-year-old Agrippina’s first wedding night, which finds Arterian hitting a limit: “Agrippina turns her face / toward or away you decide / I don’t want to imagine anymore.”

Hera Lindsay Bird, Juvenilia

(Deep Vellum Publishing)

Hera Lindsay Bird’s first widely shared poems seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere: from cartoonish dreamscapes and the global pop-cultural unconscious, from stream-of-consciousness Twitter rants (garlanded with stream-of-too-many-periods ellipses), from whatever high-meets-low, love-and-death multiverse can cough up a title like “Keats Is Dead So Fuck Me from Behind.” Where the poems were really coming from, it turned out, was New Zealand, where her debut Hera Lindsay Bird—a rarity, a self-titled poetry book—was published in 2017 by Te Herenga Waka University Press. At long last, Bird’s first North American book is being published, printing selections from Hera Lindsay Bird and the UK pamphlet Pamper Me to Hell & Back (2018) alongside several uncollected poems. The book’s wry title emphasizes unformed youth, but again and again the butts of Bird’s skeptical jokes are herself, her art, and how little the two ever develop, no matter how newfangled their surfaces appear: “The official theme of this poem is / The official theme of all my poems which is / You get in love and then you die!”

Steven Espada Dawson, Late to the Search Party

(Scribner)

Among the earliest myths told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses relates the tragicomic origins of a haunting instrument: the nymph Syrinx, pursued by the lascivious god Pan, finds safety only by being transformed into a hollow, resonant reed—out of which Pan fashions the first panpipes, or syrinx. Steven Espada Dawson’s Late to the Search Party begins with that myth’s twenty-first-century renovation: “The first time I found my brother / overdosed, he looked holy….I whittle that used syringe into / an instrument only I can play.” A brother’s drug use and decade-long disappearance are two subjects Dawson transmutes into songlike quatrains and sonnets; another is a mother dying from cancer: “She turns // each meal she won’t eat / into a rhymed couplet.” For all the tragedy of this first book—enough to preoccupy a career—Late to the Search Party is also a book of unignorable comedy, from the “too soon?” joking of its title to the ludicrous reality framed in “Salvation Sonnet,” which remembers a summer spent at a Salvation Army through the lewder objects donated there: “countless dildos, dildoes, dildi….Bad cadavers, / sometimes they’d shiver back to life.”

Ashley D. Escobar, GLIB

(Changes)

You could look at the ruler-thick lettering and high-contrast portrait on the cover of Ashley D. Escobar’s first book GLIB and conclude that GLIB is to Escobar what brat is to Charli XCX: a brash reclamation of a putdown, a consonant-chewy four-letter word, an aesthetic category as curious to its creator as to her audience. (“If I follow a glib statement with another / glib statement will it begin to make sense?” Escobar wonders.) But GLIB is also the next, reference-heavy step in a NYC-specific history of chatterbox wit: its first poem, “Post-Algonquin,” namechecks the Algonquin Round Table and, playing off Frank O’Hara, declares “It’s okay to perfectly disgraceful”; the next few poems riff on the late singer-songwriter David Berman, Frances Ha, and “the jonathans, / franzen or lethem, never sure which one is which.” If the epitome of glibness is to get away with saying anything, GLIB’s last lines do that one better, giving up on speech altogether: “I like the long beep when my dryer ends // Beeeeeeeeeeeeeeeep.”

Taylor Portela, Tranny Muse

(Unbound Edition Press)

“I am large, I contain multitudes,” Walt Whitman boasted—boldly, if a bit vaguely. One of his latest aesthetic descendants, the queer, nonbinary poet and performer Taylor Portela, is more specific about their literary and personal multitudes: their first book Tranny Muse encompasses nine books, named (like Biblical books) after different facets of Portela’s identity and stage persona: “First Book of Taylor,” “Second Book of Portela,” “Third Book of Lavender.” The gravitational center of Portela’s stylistic variety and curriculum-spanning subjects (analytic philosophy, Mormonism, the first drag queen William Dorsey Swann) is the book’s titular character, Tranny Muse, whom Portela addresses dozens of times across their talky prose poems. A queer upending of the cis-women muses idealized throughout Western poetic history, Tranny Muse is an inspiring figure not looked up to but met face to face—a confidant, a co-conspirator, and a cheerleader to Portela’s most piercing formulations: “Tranny Muse, identity is a prison; capital, the captor; everything logged becomes binary.”

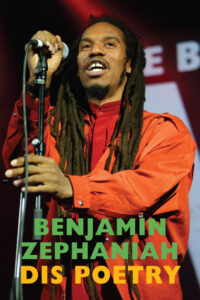

Benjamin Zephaniah, Dis Poetry: Selected Poems & Lyrics

(Bloodaxe)

Dub poet, musician, novelist, playwright, memoirist, professor, actor, antiracist and animal-rights activist, a teenager written off by one teacher as “a born failure” who became a best-selling author for adults and children, one of the proud few to turn down an OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire): Benjamin Zephaniah (1958-2023) was known for all of the above in the United Kingdom, and far too little known outside of it. The new selection Dis Poetry will acquaint Anglophone readers the world over with four decades of Zephaniah’s poems and lyrics—the former so ear-catching with anaphora and tumbling-over rhymes, the latter so thick with discourse and chitchat, that it can be hard to tell one from the other, or why the distinction even matters on the page. The selection’s title poem, from 1992’s City Psalms, is as much a classical ars poetica as a succession of verifiable bars, self-aggrandizing and self-vindicating in equal measure: “I’ve tried to be more Romantic, it does nu good for me / So I tek a Reggae Riddim an build me poetry,”