As I write this introduction, there’s a heatwave and the world is a mess. As we watch the defunding of many of the institutions that help literature get in the hands of readers, that lift up important voices, and that tell us about those voices, I am more grateful than ever for Lit Hub, whose tenth birthday I missed marking in my May column.

Lit Hub, who continues to offer an open space for us to talk about books all year long. Poetry books, no less.

July brings Paradiso, the final book in Mary Jo Bang’s trilogy of Dante translations from Graywolf, and Henri Cole’s gorgeous The Other Love, which I covered here in May, from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Meanwhile, the books in this month’s round-up offer keen reflection, observation, and interrogation, and I found these questions reverberating across the round-up:

“What were we in that moment?” (Nida Sophasarun, “Novice”)

“What if you weren’t waiting (as if sitting at the end of a long corridor, hearing the voices of the others faintly from behind a door and waiting your turn to be called in: I’m ready!) but already, even as you sat there in the hallway’s pale fluorescence, in the midst of something (your life)?” (Éireann Lorsung, “An Ampler–Zero–”)

“Will we survive? // we will not survive. // Will our children survive?” (Marissa Davis, “Parable for the Apocalypse we Built, I: The Forum”)

“Where was I going?” (James Cagney, “Donate to the Crazy Fund”)

“What do you call a person telling your body to be more like their body? Is a body more than a body?” (Cassandra Whitaker, “Hunted”).

And from Anthony Borruso’s “When Watching Jeopardy I Start to Feel Sad,” “What was that / Monty Python sketch? The one with the dead / parrot and the shopkeep who refuses/ to acknowledge its deceased state?”

*

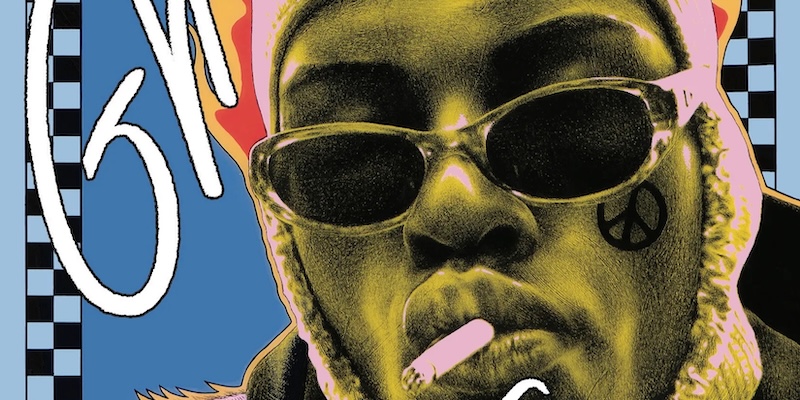

James Cagney, Ghetto Koans: A Personal Archive

(Black Lawrence Press)

Welcome to Oakland: “this city is where the rich compete in buildings / tagging territories with titanium graffiti” and “this city is a dystopian movie set / and scaring the neighbor’s gingerdoodle.” These lines are from James Cagney’s “Lemme Holla at You,” which bears the epigraph “City Hall, _____.”

Epigraphs of street names and places continue to guide the reader throughout Ghetto Koans: the epigraph for “Tina Turner’s Wig Gives Its Final Public Address” is “Charm Beauty College, Grand Ave., Oakland,” and in “Where U Try’N 2 Go,” we get “43rd St, Oakland,” where in order to get out of a house, the speaker “pinch[es] the metal lip /push it, then stick / my other finger in the hole/ where a door handle /once was.”

We follow the speaker around the city, poems taking us from the Farmer’s market, where “We buy nine dollars in cherries” to the outside of the supermarket: “Hey man, hey. // Hey man, hey. //A middle aged man waddles off the sidewalk in front of the corner grocery store.” The speaker later adds, “my pockets are more empty than his.” The more Cagney lets us in, through naming, storytelling, characterizing, the more he artfully addresses both his speaker’s liminal position as observer and the condition that the audience is (mostly) outsiders; he’s showing us around, but this can only go so far.

Cagney offers intimacy through humor–generational meditation sprawls across “What Zero Sounds Like (After Watching Teenagers Attempt to Use a Rotary Phone)” –and through moments such as in “Donate to the Crazy Fund,” when a man on the street asks for money for a shelter that “costs twenty-eight dollars / a night,” where he “was held down and raped/ by four animals,” and the staff “don’t care, man.” The poem ends with the reader stopped alongside the speaker: “Finally, the light I was waiting for turns green. / I just stand there. Where was I going?”

Marissa Davis, End of Empire

(Penguin)

Kentucky-born-and-raised poet Marissa Davis, who now lives in Paris, repurposes poetic traditions for the Anthropocene with poems such as “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Dead Fish” and the preface poem, “Lot’s Wife Triptych,” a sharp contribution to contemporary poetry’s accumulation of Lot’s wife poems.

This Lot’s Wife targets how dehumanization and environmental destruction are the inseparable foundations of an America built through enslavement: “I was stripped / of country -by // this country- this country/ pillaged” and “less soul than– flesh // technology.” And towards the end of the poem, “what peculiar triumph- to watch ruin-/ succumb to the ruin // it birthed….”

From here the poems in the collection eye the realities of who that ruin first targets. “& we could see / the barbed fate arcing / towards us,” the speaker of “Twister Tristate,” laments. The “us” is soon clarified: “for those like us–/ we, mostly just the poor, // the poor’s children, once & future // laborers, quick-forgotten.” And further, in “Altar-mondialism,” where the doubled-self reverberates in the possessive pronoun: “in my nation, we carbon-balance with the blood /of Black children.”

Ranging across the white space of the page with rigorous focus, Davis tightens into lyrical couplets in moments like “Ecclesiastes: Thirteen-Year Cicada,” which sings with “our selves less self / than a knowledge // of time, time: / our shell, our salt, // our singing wings.”

Éireann Lorsung, Pattern-book

(Carcanet Press)

Éireann Lorsung makes her UK debut with Pattern-book, which echoes Sei Shōnagon’s Pillow Book in title and in the poem “Pointilisms,” which is “in the footsteps of” Shōnagon. Perhaps her mark is on Lorsung’s general formal hybridity across the collection as well, thought this particular collection holds fast to the lyric whether through sonnets, a Dickinson-inspired acrostic, or a sputtering repeating and deleting lyrical abecedarian, an unsorted (by letter) reverberation of her extended abecedarian, “an archeology,” in her previous book, The Century.

Enriched by a palette and song born of yet a new landscape–Lorsung has lived and worked across the U.S. and Europe, and now teaches in Ireland–these poems are full of blooms: apple trees, “the purple furze on bolted artichoke,” and the “[n]ame of a flower / for cold months, hellebore—/ memory’s color.” These poems engage directly with memory, as well as both language and the act of making. “Simile” concludes, “A drawing of the world / that is the world, that I / can make. That’s making me.”

This is Lorsung’s fourth collection, including her memorable 2007 debut music for landing planes by from Milkweed, who will publish her collection Pink Theory! next year.

Pascale Petit, Beast

(Bloodaxe Books)

Pascale Petit’s ninth collection, “Beast,” begins with “that feeding frenzy I call my birth.” Piranhas are present and the mother’s face “looms.” From here we enter the mother’s body again and again, the conceit of the body morphing: “I mean the grand / in the children’s home where I clung to one leg,” as the piano keys “turn into sharks’ teeth.”

Violence in the natural world offers figures for invoking the speaker’s parents, and it’s no surprise when one sees Petit reference Louise Bourgeois directly with “Maman.” The poem “Insect Father,” begins “The moment I was born, you were a screw worm feeding on my navel,” only to turn mid-poem: “I watched you fly away from my childhood / to eat the face of God.” “Papa,” is not only “Insect Father,” but snake, and the figure in “Skinner” who directs her to “Pass me my skin,” the “fur hide” on which he would “ask me to lie on it / my arms punned out along the front paws, my legs / along the spreadeagled back paws.”

The imagery has a lineage of Plath’s intensity meets Hughes bestiary, with an emotional narrative all Petit’s own. This gripping collection from Petit, whose work has been short-listed for the T.S. Eliot prize four times, teams with surprises, though perhaps more so if you are new to her work.

Cassandra Whitaker, Wolf Devouring a Wolf Devouring a Wolf

(Jackleg Press)

Cassandra Whitaker’s debut is a sequence that moves like a long poem, pulsing with the motif of the wolf; individual poems are often split in columns or forged in prose with slashes rather than punctuation or line breaks. None of this is formally new or rare– but the forms suit the emotional circling here, repetition building into a portrait of being while portraying the context for being: Whitaker is a trans writer from Virginia.

“Growing Up in the Mouth of the Wolf” interrogates toxic masculinity, opening, “By age three men terrified me.” The speaker’s “father’s own / kingdom—steepled—a soft / cruelty.” Whitaker tackles the resulting paradox: “I did not / belong in my family / but it was clear I belonged / to my family—a thing to be shaped and shamed / and shamed and raised up / into what? A what? A wolf.”

In “Hunted,” in which the lines wrap around the outline of a wolf sketch, questions accumulate, including “What do you call a person telling your body to be more like their body? Is a body more than a body? What do you call returning to the tender places?” Other poems wrestle with love and desire amidst the “wolf’s promise.” “The Wolf I Should Have Known” snaps shut with “When he left me / the woods wheeled wild with stars.”

Nida Sophasarun, Leigh Anne Couch (editor), Novice

(Louisiana State University Press)

Nida Sophasarun’s debut, Novice, the latest book in Lousiana State University Press’s Sewanee Series, is enriched by two-decades worth of poems, reaching back to an Atlanta childhood as the daughter to Thai immigrants. “Violent Femmes,” opens poolside in 1989, while “Come Back, Shane,” offers a compelling portrait of an uncle who “rarely goes out” as “Grandma and Grandpa / don’t allow it”; in a cycle of replacement, the uncle “names each shepherd mutt / Shane, after his favorite cowboy.”

Together, the poems in this collection wield a self in reflection, forging complex portraits of key relationships: the poolside friend, parents, husband. Juxtapositions of the “orange and gray/monkeys on a pebbled beach / contemplating us” and “steam from / a slaughtered pig” in Yantze Gorge evoke early years of marriage. In “Novice,” when the twenty-three-year-old speaker visits a monastery in Chiang Mai with her father, who “wanted to join the monkhood / and this was practice,” the speaker notes, “It’s funny how/ The Way is pitted against the family unit.”

One of the collection’s highlights, “The Horses,” grapples with her mother’s illness: “At night I think about my mother–/ how she no longer inhabits / all the rooms in her body.” Later in the poem, the speaker says, “I send horses// to nod their way into her rooms,” and “It’s impossible for me to leave/ her body alone.”

Anthony Borruso, Splice

(Trio House Press)

The poems in Anthony Borruso’s debut, selected by Oliver de la Paz as winner of the 2024 Louise Bogan Award, are packed with film and TV. The TOC alone reveals topics and tone, with titles like “Semi-Autobiography as SNL Cast Member,” “Frances McDormand,” “Scorsese Dreamsong,” and “Love-Sloshed Cinema.”

Borruso’s style is playful, pointed in its humor and romps. There’s a “Ballad to Ted Williams”: “Godspeed Ted, I kid you not / your kids are keeping you / in a freezer, your severed head / atop a can of Bumble/. Bee tuna….” And in “5G Golden Shovel,” a line from Pynchon cascaded down the ends of the lines, invocations include “O Joy Reid O Jesus O Hannity, is // it enough we stare at you and think about the storm coming?”

But poems follow a mind, moving with all it has absorbed and endured. Borruso’s decompression surgery after a Chiari diagnosis—which the Mayo Clinic reports is “a condition in which brain tissue extends into the spinal canal”—becomes both subject and way of seeing, hearing, sensing. In “Resonance Imaging,” “The man behind the glass / knows the spin of my mind’s// vinyl: drops a pin where / the stem slips from the skull.”