A time there was, and a recent time, when big beasts stalked the groves of academe. This was in the last quarter or so of the 20th century, the leafy days of Althusser and Paul de Man, of the terrible twins Guattari and Deleuze, of Foucault, Derrida and Sollers, of Susan Sontag and the delightful Julia Kristeva. It was the age of theory, after the demise of the new criticism and before even a shred of cannon smoke was yet visible above the battlefields of the coming culture wars.

How sure of ourselves we were, the heirs of Adorno and Walter Benjamin. We knew, because Nietzsche had told us so, that there are no facts, only interpretations – sound familiar, from present times? – and that danger alone is the mother of morals. We listened, rapt, to the high priests of structuralism, post-structuralism, postmodernism, und so weiter. We pored in anxious excitement over the hermetic texts of the new savants, encountering sentences such as this, from the pen of a German-born academic who had been long settled in Britain, and who in the last decade of his life would mutate into a world-famous novelist: “The invariability of art is an indication that it is its own closed system, which, like that of power, projects the fear of its own entropy on to imagined affirmative or destructive endings.”

This gnomic aperçu is one of many such that might be lifted at random from Silent Catastrophes, a hefty volume of posthumously published essays on European literature in general, and on Austrian writers in particular. Those of us who admire Sebald the novelist – a warm commendation of his work, from the present reviewer, is printed on the jacket of Silent Catastrophes – will seize on this collection with the keenest anticipation. Alas, we will be sorely disappointed. The essays, with some exceptions, represent academic writing at its most convoluted, most resistant and most sterile, the deathless products of the publish-or-perish academic treadmill.

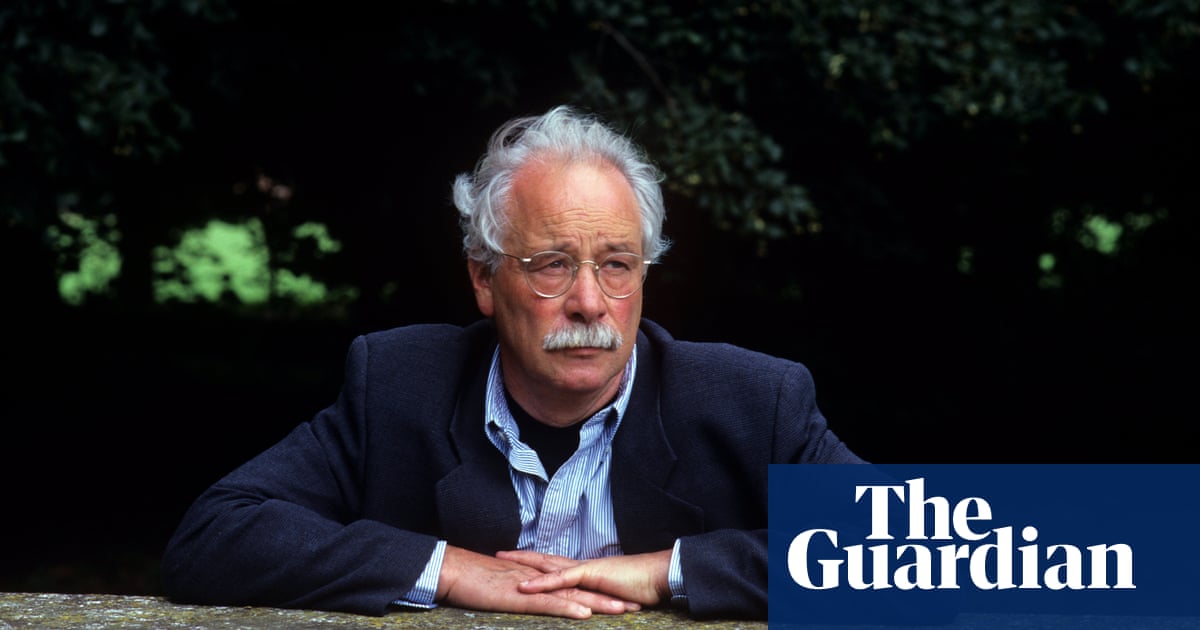

Winfried Georg Sebald, “Max” to his friends and colleagues, was born in 1944 in the small town of Wertach in southern Bavaria, close to the Austrian border. His father fought in the German army in the second world war, and that extremely loud catastrophe reverberates, though at a low level, throughout his writing. He travelled and worked in Switzerland, spent time at the University of Manchester, and in 1970 settled at the University of East Anglia, where he was still based at the time of his sudden death, at the age of 57, in 2001. It is hardly surprising, then, that his works from that final miraculum decennium concentrate on themes of travel, of displacement, of deracination and uneasy settlement.

His editor, and the translator of Silent Catastrophes, Jo Catling, who worked alongside Sebald in the German literature department at East Anglia, points out that the authors Sebald chose to write about in these essays are, for the most part, liminal figures. They are “outsiders either socially or psychologically, exiles literal and metaphorical”, such as Adalbert Stifter, Elias Canetti, Jean Améry, the poet Ernst Herbeck – who spent most of his life in an Austrian mental hospital – and, of course, Kafka.

The words heimat and unheimlich recur throughout these pages in sombre antiphony. Heimat is a state of being, a state of belonging, the resonance and weight of which the English word “home” does not adequately convey. Meanwhile, Das Unheimliche is the title of Freud’s famous essay On the Uncanny. To be without a home, then, is to be without a place where the soul may rest easy, or if not easy, then in a condition of heitere melancholie (cheerful melancholy), which is how the German publisher of these essays characterised the Sebald tone.

Silent Catastrophes is a substantial volume – though far lighter in the hand than it looks, since most publishers have given up using decent, durable paper – comprised of two separate collections of essays. The first, The Description of Misfortune: On Austrian Literature from Stifter to Handke, which despite the word “Austrian” in the title contains an extended meditation on the “death motif” in the Czech-born Franz Kafka’s novel The Castle, will be hard going for the general reader, forced to grapple with the scholarly apparatus in which the text is entangled.

The second part of the collection, Strange Homeland [Unheimliche Heimat]: Essays on Austrian Literature is slightly more approachable, and in places even enjoyable. In particular, the essay on Joseph Roth, journalist, drinker and author, most famously, of The Radetzky March (1932), is driven by Sebald’s evident enthusiasm, indeed fondness, not only for the work but for the man.

Equally but more darkly to be savoured is the demolition job carried out on Hermann Broch’s turgid monolith Bergroman (Mountain Novel). Sebald writes: “What we feel is not the intimations of transcendence that great moments in literature – and perhaps life – can give rise to, but merely a surfeit of sheer banality. In this sense, Broch’s ‘great novel’ turns out to be a complete debacle.” Now you’re talking, Max.

after newsletter promotion

It affords a reviewer no pleasure to be harsh on this book, which Jo Catling frankly declares was “a labour of love”. However, to present in the guise of a volume of mainstream essays the spade-work left over from a life of academic toil can only diminish the posthumous reputation of a writer who, in books such as The Rings of Saturn and the superb Austerlitz, showed himself to be one of the last masters from the great age of Mitteleuropean high literature that is now drawing to a close, in its own silent catastrophe.