In the canon of British true crime, the case of Dr Crippen routinely gets billed as the first “modern” murder. It wasn’t that there was anything particularly original about the doctor’s motives or methods: in January 1910 he slipped poison into his wife’s bedtime drink so that he could marry his secretary instead. Rather, it was the way that Crippen was caught that turned this run-of-the-mill suburban love triangle into an international cause célèbre.

Realising that it would only be a matter of time before his wife’s dismembered remains were discovered in the cellar of the marital home in north London, Crippen and his secretary Ethel Le Neve fled to Canada in disguise. Such was the media hoopla surrounding the case that the sharp-eyed captain of the SS Montrose quickly spotted the runaway lovers among his passengers. This was despite their unconvincing cover story of being “father and son” (the hand-holding and kissing gave the game away). Using the ship’s brand-new Marconi wireless, Capt Andrew Kendall alerted the British authorities that he had the infamous fugitives in his sight. Within hours, Insp Dew of Scotland Yard had boarded a faster ship from Liverpool with the intention of reaching Newfoundland first, so that he would be ready to arrest Dr Crippen and his companion when they made landfall. To a fascinated public, following the unfolding drama in the newspapers, it was as if time travel were being invented before their very eyes.

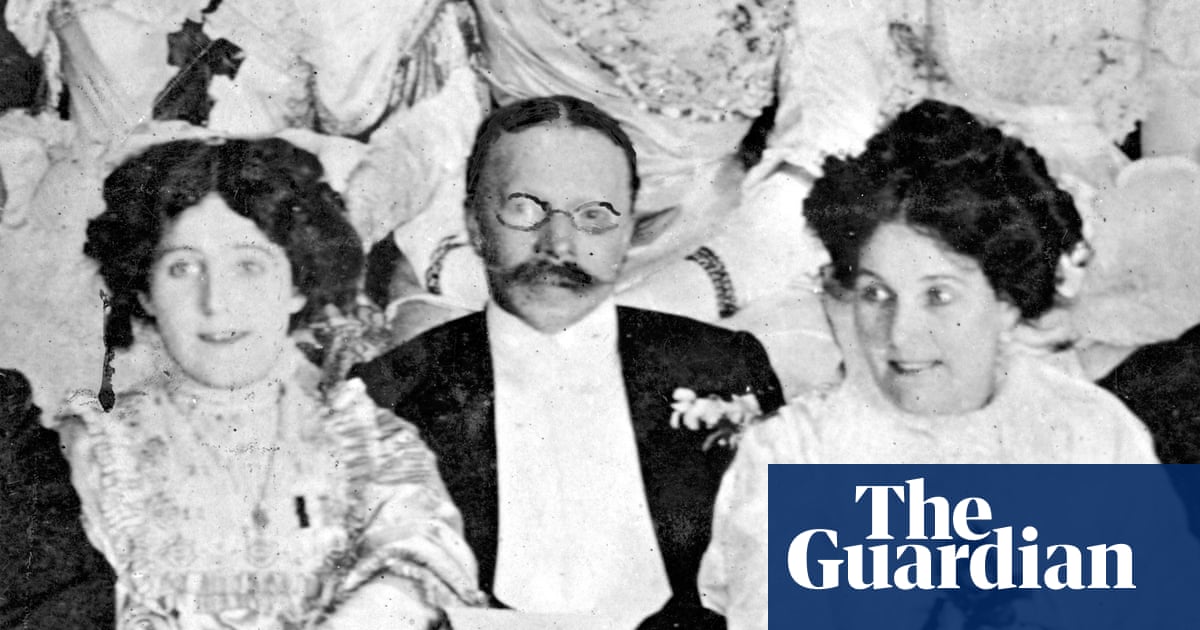

Hallie Rubenhold has form when it comes to interrogating the cliches of “classic” true crime. Her previous book, The Five, dealt with the hoary old case of Jack the Ripper but told it from his victims’ point of view, transforming them into complex subjects with histories, hopes and frailties of their own. Here she does something similar with Cora Crippen, who has been repeatedly written off as a silly, slatternly floozy who harboured ambitions of being on the stage when she should have been busy at home getting the doctor his dinner. Even Capt Kendall, who can’t possibly have met her, described Cora Crippen confidently in his memoirs as “a flashy, faithless shrew, loud-voiced, vulgar and florid”.

In the place of this preposterous caricature, Rubenhold shows us Cora, whose stage name was Belle Elmore, as an artist who loved both the creative and social aspects of stage performance. When her own singing career faltered, she threw herself into her role as treasurer of the Music Hall Ladies’ Guild, which campaigned vigorously for better working conditions and pensions for its members. After her disappearance, it was Cora’s guild sisters who went to the police with their suspicions. At the subsequent Old Bailey trial, these singers, dancers and mime artists were called to identify the bits of fabric and strands of hair that had been found mixed up with the putrid remains in the basement of 39 Hilldrop Crescent. Cora’s head was never discovered, probably because Crippen had dumped it in the nearby canal, which allowed the defence to suggest that it must be some other woman, or even man, who was in bits in his basement. Sensibly, the jury took only 27 minutes to find Crippen guilty. Le Neve, though tried as his accomplice, got off and spent the rest of her life in tight-lipped anonymity.

The Crippen case has been written about countless times before, but Rubenhold’s intention here is to divert attention away from the doctor (who, strictly speaking, was less a bona fide doctor than a pedlar of quack nostrums masquerading as homeopathic remedies) and put Cora back at the centre of the story. It is no accident that she, bold and magnificent, rather than mild and mousy Crippen, looks out from the cover of this book. If you strip away the newfangled elements of the case – the Marconi radio, the high-speed chase across the Atlantic, the saturated media coverage – what you are left with is the story of a woman who lost her life for no other reason than a man wanted her out of the way. Femicide, in other words, and as old as time itself.

after newsletter promotion