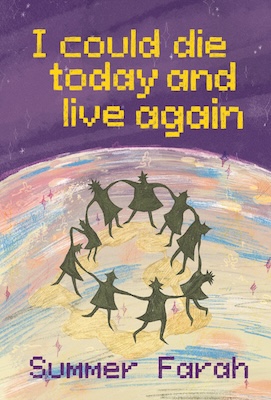

“how lonely it can be / to be a certain type of character. singular purpose. looped dialogue,” writes Summer Farah in her poetry chapbook I could die today and live again, published by Game Over Books in 2024. The collection, which explores empire, intimacy, grief, and play amidst the backdrop of The Legend of Zelda, is haunted by cycles: the cycles of the moon, of mourning, of occupation, of poetic form, and the regenerative cycles of death and rebirth within video games. What would it feel like, Farah asks, to be an NPC trapped within the endless loop of a game on repeat? How can we create growth and meaning from these patterns we find ourselves (re)living?

As I write this, it is the one-year anniversary of the current iteration of Israel’s genocide in Gaza: 365 days and 76 years of schools, hospitals, homes, and refugee camps being destroyed by bombs paid for by American tax dollars; of families being torn apart and displaced; of forced starvation and denial of access to medical care; of the targeting and erasure of entire bloodlines. It is easy to succumb to despair in the face of this unfathomable cruelty, but this also marks 365 days and 76 years of Palestinian resistance; of unprecedented international solidarity; of men risking their lives to dig children out from under the rubble; of radical, unwavering hope; of the steadfast conviction that Palestine will be free. “SOMETIMES ALL OF OUR RESISTANCE IS / UNDONE WHEN NIGHTFALL COMES,” Farah writes, “BUT WE WILL NEVER FORGET / CHAMPIONS LEAVE MEMORIES IN SUNLIGHT / IF YOU CLOSE YOUR EYES IN THE SHIMMER / YOU CAN FEEL THEIR BREATH ON YOUR SKIN.”

I’m grateful to have had the chance to talk to Summer over Zoom about obsession, persona, video games, and the peculiar way that poem excerpts proliferate on Tumblr.

Ally Ang: To start, what is your origin story with The Legend of Zelda?

Summer Farah: I’ve been playing Zelda games my whole life. I have an older brother who was really into video games, and we have a pretty big age difference—he’s six and a half years older than me—so video games were one of the things that we would do together a lot in bonding, because it’s easy to be three years old and play video games with a ten-year-old. My earliest favorite games were Pokemon and Zelda. I have really vivid memories of watching my brother play Ocarina of Time and he would be going through dialogue really fast because he’d played through the game multiple times. And I’m like four-ish, I’d just started learning how to read, and I would be like, I want to read what they’re saying. And he was like, but I already know what they’re saying. So I started reading fast, and a lot of my relationship to reading and narrative and processing is around playing games.

Zelda games are one player, but my brother would give me a controller that wasn’t connected to anything and tell me I was Navi just to make me chill out, and I would believe him. And then every time Navi goes away—because she’s not there all the time—I’d be like, where did I go? And he’d say, I’m protecting you. Don’t worry. So that’s my origin story with Zelda, becoming a person alongside playing the games. I’ve played all of them throughout my life. I was just playing Twilight Princess before we got on the call.

AA: I want to talk about the two epigraphs that open the collection, one from Etel Adnan (“Such apprehension, such madness! Is the sea aware that her heroic beauty may be in disuse, someday? The moon never experienced the sinking of empires that she witnessed; day after day, she longs for a shimmering heat”) and one from Kamaro from Majora’s Mask (“I am disappointed, oh moon. I have died!”) I think these epigraphs do a great job of preparing the reader for both the world of references and influences that you’re drawing upon in this book, and for some of the themes and motifs that recur throughout the book, including the moon, death, and empire. You are a poet who is unafraid to reference and you build a rich landscape of literary and cultural references in all your work, so how did you land on these two epigraphs to open the book?

SF: When I was far in the process of writing and editing the book, I was spending a lot of time with Etel Adnan’s work. I’d been reading her off and on for a while and considered her a writer that was theoretically important to me because of the artistic communities that I’m in and knowing her legacies. I liked her work, but I wasn’t as immersed in it as I am now. When I was editing the book I was reading Sea and Fog. There’s an eeriness in her work, a kind of surreal mystic feeling that her language is so encased in, that feels like you have a cool breeze around you, and that can either be comforting or isolating. That’s my favorite thing when I read, and it’s also one of the things that really draws me to a lot of Zelda games, particularly Majora’s Mask. The book takes inspiration from all Zelda games, but Majora’s Mask is kind of like the anchoring game. As I was reading Etel Adnan’s work, I was like, wow, the vibes are like Zelda! It’s fun to recognize the repetitions of what I’m drawn to in such disparate artworks.

I wanted to frame the book in some way outside of games, because it is so involved with games, so I was thinking about what else this work is in conversation with. It’s also an attempt at anti-imperial writing or critiquing empire, so I was trying to think about it in lineage with the writers I’m most drawn to for their criticisms of empire as well as their art writing. Etel Adnan is doing both of those things. At the same time, it felt like a good window into the things that I’m always pushing together in my head and making hold hands.

With the epigraph from Majora’s Mask, my work is often concerned with death, and Majora’s Mask is a game where you are putting on the faces of characters who have died. That quote is a character’s last words to you. I found something really compelling in that phrase, in that lament to the moon, especially as the moon is an empirical figure in Majora’s Mask. Out of context, it felt really beautiful, and in context, it felt really sad. I liked thinking about these two addresses that are, again, from very disparate things, but very connected.

AA: You are someone who I think of as reveling and indulging in your various obsessions through your writing, whether that be Mitski or Supernatural or Zelda. The depth of your love for your obsessions is evident in your work, but it’s not an uncritical love. In your endnote about the poem “IN GERUDO VALLEY,” you call out early racist depictions about the Gerudo people in the franchise and write about feeling conflicted about playing the game in their corner of the map. How did you approach writing this poem, and how do you more generally navigate writing about—to use a dated phrase—problematic faves?

SF: I had a lot of trashed drafts about Gerudo. I was thinking a lot about Ganondorf and how he’s the only man born into this desert society and he is the root of all evil, and there is this wholehearted villainizing of this man from the desert. My brother and I talk about this sometimes. There is this interesting recognition when you’re a kid playing these games and you’re like, oh, this fantasy setting is supposed to be inspired by my culture, and they’re the villains; that’s kind of weird and it makes me uncomfortable. But I never really thought about it that deeply.

I don’t really play first person shooters or games that are very engaged with violence against Arabs, but the reality is that JRPGs, Japanese role-playing games, are super Orientalist. They have baffling depictions of West Asia and Muslim nations; it’s kind of funny sometimes—horrifying, but super fascinating. I play a lot of JRPGs that have a medieval fantasy setting and so I see it a lot, and I mean, it bothers me, but it’s not the worst thing in the world. What gets me more is when I log on and I see the ways these depictions are held by fans and players. There’s an uncritical embrace of these depictions and a wholehearted indulgence in the violence of sexualization of these vaguely West Asian/North African Muslim women. What does it mean to think that it’s really awesome that Gerudo is like this?

Tears of the Kingdom is doing a lot of work to try to correct this racist history. There’s less villainizing, there’s more of a vibrance to the region, and it feels like a well developed region so it’s fun to go there.

I feel like a weird responsibility as a Palestinian player of Zelda games to be like, let’s think about it. But I don’t want to all the time! So I think that’s what a lot of my failed drafts were trying to poke at, but ultimately it didn’t feel honest enough, because my experience of playing the games with regards to Gerudo was weird, but the sense of recognition and fondness outweighed the understanding of violence in my own playing. It wasn’t until I was exposed to fandom that I realized the potential for violence. And since the book is very much about the act of playing with loved ones or putting yourself into the game, the criticisms didn’t feel honest in the poem. I think I could probably do it in an essay, but a poem didn’t feel like the right space and this book didn’t feel like the right space.

AA: This chapbook uses a variety of poetic forms—including the pantoum, contrapuntal, and concrete poems—but one in particular that recurs throughout this work (and your work in general) is the prose poem. In your interview on the Poet Talk podcast with Jody Chan & Sanna Wani, you talk about the prose poem’s propulsive quality and frantic energy being something that draws you to it, but I was wondering if you could talk a bit about how you approach the line/line breaks in prose poems and what drew you to prose poems for this chapbook in particular.

SF: I draft a lot in prose poems—maybe not so much anymore, but when I was writing the book, every poem’s first draft was a prose poem, and then as I went through phases of editing, they became what they were. Eventually, I had a book that only had one prose poem in it, and I was like, that’s not me.

I like the neatness and the tightness of a prose poem. When it comes to thinking about the line, I like the different ways to indicate space and breath in a prose poem like caesura, or slashes, or playing with punctuation. It feels like there’s more opportunities to play with what that break intends. A slash feels different than a caesura which feels different than a hard stop with a period, or the kind of rhythm that you can create with a very, very long list with no punctuation at all, letting words run into each other. It feels like everything is in a container, and you’re shaking it, and it’s landing in a different way.

It also felt apt for a game book where I’m turning hyperfixation into something productive. I think that’s a lot of my writing in general—maybe a lot of people’s writing—the excising of an obsession. I’m a yapper. I talk a lot. I can go on and on and on a lot about the things that I like, and the prose block feels aligned with that act and intention.

The prose poems in the book are the more interior poems. They’re the ones that feel more in my voice than in the player voice that I blend with my own throughout. It was very intentional to signal that we’re tapping into something that is more genuinely Summer. Originally, when I only had one prose poem, I was like, well, this book doesn’t really feel like me at this point. So going back in, the last two poems I wrote were “INTERLUDE: PARALLEL PLAYING W/U” and the last poem. Those are both 100% me, as much as the poet’s voice can be me. Those are very intentionally breaking away from the facade of the player character lens. And I was like, well, they gotta be prose poems because that is when I’m my most honest, vulnerable, clear self.

AA: Throughout the collection you have persona poems about different NPCs, like the moon children of Majora’s Mask and the “snot-bubble child on Outset Island” of Wind Waker. As a player, what is your relationship to the NPCs of the Zelda franchise, and as a poet, how did you decide on such a polyvocal collection (rather than, for example, having the whole collection be from the perspective of the player character)?

SF: I wanted to think about the implications of cycles within the series. I think a lot about how Link, Zelda, and Ganondorf are stuck in this cycle, but then there is a whole world that is also living in the context of the game. My favorite Zelda games have the most vibrant NPCs, like Wind Waker. Everyone on every island is distinct and has their own individual relationship to the player character. In a lot of the art that I like to spend time with, I’m interested in intimacy and companionship, which I know is maybe a little baby brained or problematic sometimes in that the TV is not your friend. But I fell in love with art because of this sense of intimacy and companionship and the dependability of repetition, of something being on every Thursday, or in the case of Zelda games, the familiar things that you can latch onto in every game and the newness in which they occur.

A slash feels different than a caesura which feels different than a hard stop with a period, or the kind of rhythm that you can create with no punctuation at all, letting words run into each other.

I wanted to think about what the consequences are for the others in the world that the game is building. The moon children are so freaky and hollow that I felt a lot of freedom to project onto them. They’re genderless, they don’t speak very much, and they’re kind of just scattered about. There’s a sense of collectivity through them, so what if it’s a “me and my girls” kind of thing?

I thought about figures that were striking to me, that would stop me from continuing on with the story, characters that I would always talk to if I entered an area. Like the couple in the square that’s always spinning, I always go to talk to them. The kid on Outset Island, that was like my niece—when she first started experiencing colds, she didn’t like it when we cleaned her face. She doesn’t like it when you take stuff from her, and that extends to her boogers. So I was cleaning a lot of toddler snot, and sometimes it’d be like, all right, fine, live with snot on your face. And my brother and I would joke that she’s like that little kid on Outset Island that’s always sneezing. It’s this dual projection of what were the things that I was drawn to, that I would always want to talk to as if they were my friend, and then, when I think of the things that my life is filled with now, how do they appear in the game?

AA: “INTERLUDE: PARALLEL PLAYING W/U” is one of my favorite poems, partially because it’s so surprising in the trajectory of the book. It feels like we’re stepping out of the game into the living room we’re playing it in, and it also feels like the speaker of this poem is the closest to you and not an obvious persona. Can you talk about how you decided where this poem would go and what shift it signals in the remainder of the collection?

SF: That was one of the last ones I wrote because after a conversation with my editor, MJ, I realized the book was kind of a bummer and playing video games should be fun, so I really wanted to have fun. I wanted to remind myself that I enjoy playing games and I’m writing about them because they’re a thing I do to enjoy myself.

In thinking about the order, I wanted it to feel like you’re starting a new game: there’s the stage setting where you’re getting lore and context and you have your player character with their basic personality, but then as you play you get more attached to the story and start projecting yourself on the player character and the world becomes more in depth because of what you’re giving to it. “INTERLUDE” coming after “ODE TO THE SNOT-BUBBLE CHILD ON OUTSET ISLAND” felt like a moment of really strong projection and fixation. I wanted that poem to feel like when you realize you’ve been playing for six hours and it’s dark outside, allowing the reader to pull away from the game and reset and think about why they’re here, reading a book about video games.

“INTERLUDE” is very engaged with friendship and community, and falling back into the book with “ELEGY FOR LOST FRIENDS” and then the climax and denouement of the book felt right. There are some games that tell you to rest your eyes so I wanted it to feel like that.

AA: Repetition, rebirth, and memory are very significant to this collection, both in terms of subject matter and in the structure of the book and the poems themselves. The reader finds themselves reckoning with these cycles of life, death, erasure, remembrance, grief that at times feel liberating (the ability to start over or reset) and at other times feels doomed (like how occupation wears different faces but the violence of it remains the same). How do you, in your poems and in your life, reckon with or resist the hopelessness of feeling trapped in these cycles?

SF: I was at a reading yesterday and one of the poets I was reading with read June Jordan’s “Apologies to All the People in Lebanon,” and he was like, this poem was written in the 1980s but it could’ve been written today. And that makes it a useful poem to read to contextualize an emotional moment as we see Lebanon continue to be bombarded by Israel, but it’s also devastating that there is a continued relevance for that work. I am always holding that when you revisit older literature from 40 or 100 years ago, it can feel overwhelming because it’s like nothing has changed, but it’s useful to have those words. I will still feel sad and fucked up that we’re talking about the same things, dispelling the same propaganda, fighting the same battles, but now I can use these arguments and the work that has already been done to push things forward.

In games you can try something over and over again, and if it keeps not working, you can do something different and sometimes it works. I feel bad and upset all the time thinking about the world: it’s been a year of genocide in Gaza and the climate’s getting worse and everything’s kind of getting worse. I know that there’s always been times when it’s felt like the worst that things could possibly be, and it takes people thinking about those past moments and using those tools to build better tools. With repetition, there comes knowledge and education and you can get stronger and sharper for whatever the next big, terrible thing in the world is. It’s never a clean slate: things might happen again but it’s not like things didn’t also happen yesterday, and we learned from them, so we can hold yesterday as we go through it again today, and it’ll be different. It’ll always be different.

AA: What has it been like to have this chapbook out in the world? What has surprised you about the experience?

I always try to acknowledge that the book that I’ve made doesn’t exist without the histories and legacies of resistance and people fighting occupation.

SF: It’s been weird. I’ve done zines before, self-published DIY kind of things, and it’s always fun to know that people are holding something that I put together. But in the case of this book, it’s releasing into the worst fucking time ever, so I struggle with the desire to push it the way I might’ve if it came out a few years ago. I’m not the biggest self-promo person in the first place because it feels weird, but it’s been useful in some ways to have attention on me so I can use it to support people in Gaza.

I always try to acknowledge that the book that I’ve made doesn’t exist without the histories and legacies of resistance and people fighting occupation. I describe the book as an allegory for how empire corrupts childhood, so if I’m to read the book in a space and benefit from it in any way, whether that be monetary or just someone being nice to me, it also has to honor the real children whose lives are being corrupted by empire.

I’m weird and obsessive and anxious so I search my name every day to see if anyone’s talking about my poems. I love to look at Tumblr to see what people are saying about my work. It’s honestly surprising that it’s selling—not in a self-deprecating way, but it’s cool that people are holding something that I made. I like to share things with people; I like the idea that my voice is in their head or they’re spending time with it. And the fact that I got to do a tour with a chapbook is really fucking awesome. I feel grateful that there were people at my stops! That was also surprising, that people showed up to see me do poems. I guess these are all very basic low self-esteem writer things.

AA: I’m so curious, what do you see people saying about your work on Tumblr?

SF: There was this one account that was sharing excerpts from various poems, and what was fascinating is that they didn’t say which poems they were from, they just named the book itself. These excerpts were so pulled out of context that it’s kind of awesome. I loved seeing people tagging their favorite fictional characters. I was like, this is what it’s all about! It’s also super fascinating to see the ways that—and this isn’t to be mean or critical—people are often incurious and don’t read what it is that they’re quoting or sharing or engaging with. I’ve seen excerpts from this one blog reposted on Twitter or Instagram or used in graphics on Tumblr, and it’s still not saying the title of the poem. The book’s title has become the poems’ title. There’s this layered engagement with the work where the excerpt itself is taking on a life of its own outside of context and it’s super interesting to see that happening and be like, how far will this go?

I love seeing Richard Siken talking to people about his work. I think it’s so funny. Early on when he started being super active on Twitter, it was clear that so many people never read his books and had only read the lines that people use in GIF sets on Tumblr. Like, have some humility! Go to the library! But he’s a very successful writer who sold thousands of copies of his debut; I’m just a guy publishing with a little indie press. It’s interesting that those processes happen to everyone.

AA: I mean, who knows? Maybe you’ll be the next Richard Siken and people will be asking you big life questions like you’re an oracle on Twitter.

SF: Actually, I would love that, because as much as he’s online, I’m online. I would love to be doing something more useful if I could, like helping a teenager out. That would be awesome.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.