Imagine, for a moment, that you’re in London in the mid-1840s, and you’ve decided to have your portrait taken by a photographer for the very first time. The studio is open only during daylight hours, so in an English winter it closes around 4 p.m.

Article continues after advertisement

It’s located in the upper floors of a building, for better access to sunlight; after walking up the stairs and entering the studio, you notice blue-tinted skylights across the ceiling. By some miracle, it’s not raining, and there’s little fog, which is fortunate: you’ve read that in duller weather the exposure time would be longer. If the photographer is diligent, the glass will be clean, and not grimy with soot and coal from the city’s industries.

If you’re a woman, you’ll be glad that you had the privacy of a women-only waiting room in which you could check your appearance. You’re wearing satin, which you read was best for photographic portraits. You also read that, while posing, to avoid your mouth looking too severe, it helps to say the word prunes.

You spot the camera, a wooden, boxlike object with an intimidatingly large brass tube at the front, stranger in person than in the drawings you’ve seen in the press. Opposite it, on a raised dais, you see a chair and a vertical iron rod with a clamp. The photographer fiddles with a series of blinds to adjust the light.

After you are seated in the chair, the photographer, or his assistant if he has one, positions the clamp to firmly hold the back of your head. It keeps you in a still but stiff upright position. He tells you to make a fist or clasp your skirt or the chair, anything to stop the merest tremble in your hands, which are now slightly sweaty because it’s warm under the skylights and you’re getting nervous.

It feels an interminable amount of time, although the photographer reveals that the exposure, which he estimated by the light and his own experience, was a mere twenty seconds.

The photographer disappears into an anteroom, returning with something in his hands that he puts into the camera. He says it’s a plateholder, and then he fusses with the camera some more and tells you not to move under any circumstances, and now the moment has come. He uncaps the lens and counts the exposure.

You’ve watched all of this without (hopefully) a flicker of movement: you’re fastened in position, hot under the skylights, and trying to mouth the word prunes. It feels an interminable amount of time, although the photographer reveals that the exposure, which he estimated by the light and his own experience, was a mere twenty seconds. When at last it’s over, and the photographer has reappeared from his mysterious darkroom, he presents you with your portrait.

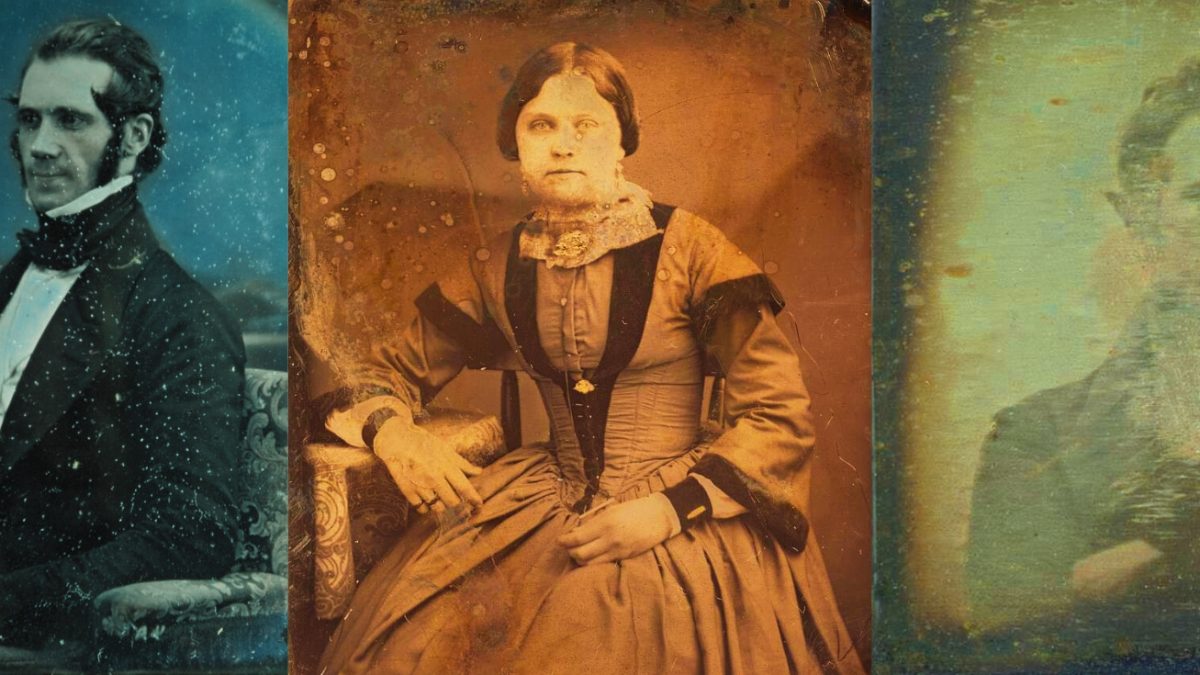

It’s a daguerreotype: a portrait on a silver-coated metal plate, protected by a glass cover, mounted in a brass frame, in a case lined with velvet, wrapped in leather. It’s small, but for the first time in your life, you have a permanent impression of how you look, or at least, how you looked at that moment, as the light filtered down through the blue glass, into the lens, and onto the plate, capturing you, or a version of you.

Maybe you’re charmed by it. Maybe you’re horrified. (There’s a decent chance you’re horrified. “The daguerreotype does not flatter,” wrote one French commentator, with a degree of understatement. Another said, more brutally, that some daguerreotype portraits “resemble fried fish stuck fast to a silver plate.”)

Maybe it is a keepsake for your children. You don’t have any photographs of your own parents; no one does. Their faces only exist in your memory unless you could afford a painted portrait. Even then, a painting is subjective, more flattering than accurate, whereas this new daguerreotype process is said to be an imprint of nature, drawn by the sun itself. What you’re now holding in your hands is the first photographic record of you, conjured up by a camera, chemicals, and light.

Although nineteenth-century photography might be commonly associated with a somber, monochrome world of stiff portraits and slightly dull landscapes, the decades after photography’s introduction in 1839 were also a time of bold innovation. Here was a new medium, bursting with potential, ready to be explored with new technology, new approaches, and, occasionally, some highly risky endeavors.

The stories behind these innovations are the subject of this book. Pick any seemingly contemporary photographic genre—street photography, say, or underwater photography—and you’ll find its antecedents in nineteenth-century photography. These innovations were sometimes misguided, occasionally obsessive, periodically dangerous, and perpetually fascinating. They also shaped photography as we know it, guided developments in art, and revealed new understandings in science.

But every successful photograph is preceded by failures. This was especially true for photography’s beginnings, after years of experimentation, with the daguerreotype in 1839.

The experience of seeing a daguerreotype for the first time was utterly revelatory. “It is hardly saying too much to call them miraculous,” wrote the scientist Sir John Herschel, from Paris, in 1839. “It baffles belief,” wrote Scottish physicist James David Forbes.

An American diplomat, Robert Walsh, wrote in March 1839 that “it would be impossible for me to express the admiration which they produced. I can convey to you no idea of the exquisite perfection of the copies of objects and scenes, effected in ten minutes by the action of simple solar light.”

Walsh wasn’t alone in his inability to describe the daguerreotype. Even some journalists were lost for words. “Briefly to explain it: it enables him to combine with the camera obscura an engraving power—that is, by an apparatus, at once to receive a reflection of the scene without, and to fix its forms and tints indelibly in metal in chiaroscuro,” wrote the British literary journal The Athenaeum, not briefly at all. Daguerre’s “photogenic drawings” were “drawings from nature through the medium of the rays of the sun,” asserted The Morning Chronicle.

The Sun newspaper, after witnessing a demonstration of the process, tried to keep it simple: “This machine, or rather apparatus, for taking, in some fifteen minutes, an exact likeness of any external object.” The reality was that no one had seen anything like the daguerreotype before.

The daguerreotype was announced to the Académie des Sciences in Paris on January 7, 1839, by the renowned French scientist François Arago, on behalf of the daguerreotype’s inventor, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. “In Daguerre’s camera, light itself produces the shapes and proportions of the objects outside it, with an almost mathematical precision,” Arago said. But he didn’t reveal how it worked. The process needed to remain a mystery so that Daguerre and the French government could negotiate a purchase of the rights. Months of speculation followed.

Daguerre was a talented artist who had moved to Paris as a teenager to apprentice as a scene painter at the Paris Opera. In July 1822, at age thirty-four, Daguerre launched the Diorama, an enormously successful visual spectacle that combined vast translucent paintings and clever illumination to give startlingly realistic effects.

At some point after this, Daguerre had the idea to capture an image with light rather than paintbrushes. After several years of frustrating experiments, he learned that a man named Nicéphore Niépce had been working on a similar idea for years. Niépce is the creator of the world’s oldest surviving photograph, a view from a window that he captured around 1826. The exposure time was about eight hours.

At the end of 1829, Niépce and Daguerre entered into a partnership to share results of their experiments and work toward their common goal. Because Niepce was in Chalon-sur-Saône, in eastern France, and Daguerre was in Paris, they communicated by letter, in code, both as a shorthand and lest anyone should intercept their correspondence and learn about their experiments.

Less than four years into their partnership, in 1833, Niépce died. Daguerre continued with the work until at last it was ready. In 1838, he met with Arago about his new “daguerreotype” process.

Once the French government and Daguerre had agreed on their terms, Arago revealed the technical details at the Palais de l’Institut in Paris on August 19, 1839. The event was so popular that crowds stood in the vestibule of the Palais, as more people waited outside. Daguerre published a manual about the process, which became a bestseller. In September, he gave public demonstrations in Paris.

By December, the clamor for the daguerreotype was such that a French artist drew a humorous cartoon of “daguerrotypomania.” It shows a chaotic scene of vast crowds lining up for daguerreotypes, cameras pointing in every direction, bottles of chemicals, and a group of suicidal engravers hanging from gallows.

But the daguerreotype was not the only photographic process that was revealed in 1839. Arago’s announcement had prompted an Englishman named William Henry Fox Talbot to announce his own experiments in photography, and rush to claim priority over Daguerre.

Talbot was an exceedingly well-educated Victorian gentleman. His family home, and the source of his income, was Lacock Abbey, a sixteenth-century manor house in Wiltshire. After attending Harrow School, Talbot studied mathematics at Cambridge University, where he also did things like translate part of Macbeth into Greek verse.

But what he couldn’t do particularly well was draw. While at Lake Como, Italy, in 1833, he attempted a sketch with the help of camera lucida, a prism that artists used to superimpose a scene onto their paper. But it didn’t help Talbot: he found his efforts horrendous, and wished that instead he could “imprint” the scene onto paper directly.

Upon his return to England, Talbot experimented with sensitizing paper to light using sodium chloride and silver nitrate. He placed an object—a leaf, for example—on the sensitized paper, and exposed it to the sun. The shape of the object stayed white, and the rest of the paper turned dark. He called this “Photogenic Drawing.”

He then tried multiple coatings of the solution; when he put this paper in the back of a small wooden box with a microscope eyepiece, after a long exposure, it produced very small, faint images. But instead of continuing to improve his work, Talbot, in an extraordinary display of shortsightedness, stopped his experiments.

When news of Daguerre’s invention reached England, Talbot was alarmed. He later claimed that he had been preparing, at the end of 1838, to share the results of his experiments in 1839.

Perhaps this was true, or perhaps he said it to mitigate his embarrassment, for he had not so much been upstaged by Daguerre as he had missed his cue entirely, and was now left floundering in the wings. His own mother even wrote him a letter where she said, “I shall ever wish it had been otherwise. This is at least the second time the same sort of thing has happened.”

At the end of January 1839, Talbot’s paper on his Photogenic Drawing technique was presented to the Royal Society. But the daguerreotype had already captured the world’s imagination.

Of course, the invention of photography also has a prehistory. Before Daguerre, Talbot, and Niépce, there was Thomas Wedgwood, who experimented with coating paper with silver nitrate and exposing it to light in the early 1800s; he couldn’t figure out how to make the image permanent. Before Wedgwood, there was Elizabeth Fulhame, whose 1794 treatise included observations of the effect of light on silver and gold salts. But the start of photography as we know it was in 1839, with these two very different processes.

To make a daguerreotype, the operator took a highly polished copper plate coated with silver and sensitized it in a box with iodine fumes. The operator then put the plate in a lightproof holder and inserted it in the camera. To expose the plate, the operator removed the slide that had covered the sensitized plate, and the lens cap.

After exposure—which was highly variable and judged by “observation and experiment,” according to one manual—the plate was taken into the darkroom and placed over heated mercury, which released vapors to bring out the image. The operator then needed to fix the image, to stop the light from affecting it further; initially this was done with common salt, and then sodium hyposulphate, or hypo, as it became known.

(Hypo, now known as sodium thiosulfate, is still used as a fixer in darkrooms.) The daguerreotype was then rinsed in water, dried, covered with glass and sealed to protect the image, and mounted in a case.

A daguerreotype had substance; it was a direct positive image made without a negative, and it was also an object. The only way to reproduce a daguerreotype was to re-daguerreotype it. It was a one-of-a-kind, highly detailed, sharp image with a reflective surface, which is why it was sometimes called a “mirror with a memory.”

At first, the exposure times for the daguerreotype made portraiture impossible.

At first, the exposure times for the daguerreotype made portraiture impossible. This quickly changed. Experiments with the photographic chemicals and improvements to the cameras meant that exposure times were soon sufficiently short to allow for the human face to be photographed.

Even so, they were not exactly brief, and also highly weather-dependent: in 1841, a daguerreotypist in London, Antoine Claudet, estimated that exposures varied between ten and twenty seconds in June, and sixty to ninety seconds in September. One of Claudet’s subjects recalled the experience of a sixty-second exposure, during which he sat in an open—air rooftop studio on a bright sunny day, while his unblinking eyes streamed with tears.

Early that same year, Talbot patented his own improved process that he called the calotype. To make a calotype, the operator sensitized a sheet of good-quality writing paper with silver nitrate and potassium iodide. The paper was then washed, dried, further sensitized with a solution of gallic acid and silver nitrate, then loaded into a camera and exposed.

After it was removed from the camera, the paper still appeared blank: the image only appeared once the paper was washed with a fresh solution of gallo-nitrate of silver. The image was then stabilized with potassium bromide, before the widespread adoption of hypo as a fixer.

The result was a paper negative, from which multiple paper copies could be made through contact printing. The disadvantage was that the fibers and textures of the paper made the image less sharp. Visually, a calotype has a slightly hazy quality, in contrast to the daguerreotype’s metallic clarity.

Although the daguerreotype and the calotype were rival processes, in reality the daguerreotype dominated photography’s first decade. But the rivalry still stymied English photographers. Daguerre took out a patent in England and Wales, even though he sold the process to the French government, which was, ostensibly at least, making it available worldwide. Talbot, perhaps in reaction to being so publicly bested by Daguerre, rigorously enforced his calotype patent. Together, these patents inhibited photographers in England for about a decade.

Talbot was widely and loudly criticized for his actions. One journal wrote that Talbot seemed to think his patent “secures to himself a complete monopoly of the sunshine”; another described a “practice of intimidation” and a “disgraceful love for patented monopolies.”

In a portrait from 1864, Talbot poses with a lens in his hands, as though he’s trying to claim recognition, even while his face looks out warily; it’s a pose of regret. He did not then know that the fundamentals of his process—a negative that produced multiple positives—would be the future of photography.

As always, technology progressed, and newer, better, faster processes were born. One of the most influential was the wet collodion process. Invented in 1851, it combined the best of the daguerreotype and the calotype: it created superbly sharp images on glass plate negatives that could be reproduced as paper prints.

Talbot, in a spectacular example of overreach and poor self-awareness, claimed this new process was in breach of his patent and sued. He suffered some very bad press as a result; he also lost the case. Conversely, the man who invented the wet collodion process, a sculptor-turned-photographer named Frederick Scott Archer, didn’t patent it, and never saw a cent.

The wet collodion process dominated photography for nearly three decades. The first step was to create the collodion: gun cotton (cotton soaked in nitric and sulfuric acids and dried) was dissolved in ether and alcohol. The collodion was then mixed with potassium iodide to create a syrupy, sticky liquid, which the photographer poured evenly across a clean glass plate. The next step was to sensitize the plate in a darkroom by dipping it in silver nitrate.

Now it was ready to insert into the camera’s lightproof plateholder. The photographer had to both expose and develop the plate while it was still wet, so there was no time to be leisurely. If the chemicals dried out, they lost their sensitivity and couldn’t create an image. From start to finish, the photographer had perhaps fifteen minutes.

This meant having all the photographic chemicals and equipment to hand. If you wanted to travel or take a landscape view, for example, you needed to carry everything with you to your chosen location—chemicals, water, portable darkroom tent, camera, tripod, developing trays, glass plates, and measuring apparatus. (And then carry them all back again.) One photographer recalled arriving at a train station on a Saturday morning in the early 1860s for a photographic outing with a hundred and twenty pounds of equipment.

Photography is, of course, based in science, and it evolved alongside scientific knowledge. In the late 1870s, the wet plate process was replaced by the wildly more convenient gelatin dry plate process. It was a technological revolution: it allowed plates to be prepared in advance, and purchased directly from manufacturers, which had far-reaching consequences across the photographic industry.

Once a photographer had a glass plate negative, they produced a positive through contact printing. The negative was placed in direct contact with sensitized paper in a frame and exposed to the sun; as a result, the size of the negative dictated the size of the print. (Although it was possible to enlarge a print, it was difficult, and only in the 1880s, with improvements to paper and artificial light sources, did enlarging become a more workable process.)

One of the most popular and enduring printing materials was albumen paper, which was introduced in the early 1850s by French photographer Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard. As the name suggests, albumen paper started with a solution of egg whites, beaten with salt, into which the paper was floated and then dried. When it was time to make the print, the photographer dipped the paper (albumen-side down) into silver nitrate, dried it again, then positioned it in a frame, under a negative, in sunlight.

Once the printing was complete, the photographer washed the print, toned it (typically with a gold chloride solution) to enhance its appearance and longevity, and fixed it. The result was a smooth, glossy, sharp print.

One result of albumen paper’s popularity—and it dominated until the early 1890s—was an excess of egg yolks. For photographers who produced their own albumen paper at home and needed to use up egg yolks, one photographic journal printed a recipe for a yolk-filled “photographer’s cheesecake.” (If you’re interested in trying out the recipe, it’s in this book’s endnotes.)

In the commercial manufacture of albumen paper, the quantities of egg use were staggering. In Dresden, Germany, which was the center of albumen paper production, in the late 1880s one factory alone used over six million eggs in a single year.

The separating of those eggs was all done by hand, by women employees, and the yolks were sent to use in leather tanning, or to bakers. The factories in Dresden also initiated a process of fermenting the egg white, which made for a glossier paper; it also imparted a distinct smell.

But paper wasn’t the only printing surface used, which takes us into one of the weirder sides of nineteenth-century photography. In the 1880s and 1890s, in Paris and Chicago, young women and men had portrait photographs printed onto their skin. They didn’t last, which, reported The Photographic News, was not a bad thing: “To the fickle the want of permanence will not be regarded as a disadvantage.”

Fingernails were also used as a highly unusual (and temporary) surface for printing photographs. One article suggested positioning the portrait so that the head was near the nail bed; otherwise when the wearer cut their nails, the portrait would be decapitated.

With the sheer number of chemicals involved in nineteenth-century photography, practitioners had a host of novel and exciting ways to injure themselves. Daguerreotypists, for example, were exposed to toxic mercury and iodine vapors every time they made an image. An American daguerreotypist named Jeremiah Gurney nearly died in 1852 after continued exposure to mercury. But that was just the beginning.

“I have only to enumerate soluble cotton, nitro-glucose, ether, alcohol, bromine, iodine, ammonia, fulminates of gold and silver, to call up a battery of chemicals the use and combination of which would readily destroy a dwelling-house and all contained therein, either by fire, explosion, or suffocation,” wrote R. J. Flower in the British Journal of Photography, in 1869. This was not hyperbole.

The components of collodion were gun cotton, ether, and alcohol. Gun cotton is an explosive, and ether is volatile and highly flammable. Fires or explosions in photographic studios and factories occurred with alarming frequency.

Just one example, as noted by photo historian Bill Jay in his book Cyanide & Spirits, involved an unfortunate photo chemist who experienced two explosions of gun cotton in two years. The first occurred as the gun cotton was drying; it exploded with such force that it blew out both the front and back windows in his studio. The second explosion, two years later, happened as he was packing gun cotton into a cask, and it killed him.

The risks from ether were also considerable, particularly given the abundance of open flames in the nineteenth century. In 1858, Photographic Notes recounted “the story of a photographer who enters his laboratory with a lighted candle, a thing which he has foolishly done a hundred times before; he cracks a bottle of ether, and half-an-ounce, not more, is spilled upon the floor; presently the vapor reaches the light, and in two minutes the whole place is a raging furnace.”

Some photographers also opted to use cyanide of potassium, a poison, either as a fixing agent for negatives or to remove stains on skin caused by silver nitrate. One 1857 manual, The Photographer’s Pocket Companion, suggested applying a saturated solution of cyanide on stained fingers and hands. The author then noted, “cyanide of potassium is a very poisonous substance, and if allowed to come in contact with ruptures on the hands, oftentimes produces disastrous results.”

The “oftentimes produces disastrous results” is an understatement. Cyanide in an open wound was a ghastly experience. One photographer who cut his thumb on a glass plate and then accidentally rested his hand in cyanide discovered that “the smarting pain was almost intolerable.” Multiple photographers suffered from pain, swelling, amputation, and even death from the absorption of cyanide through a skin abrasion.

Some photographers experienced “cyanide sores,” which they treated with rainwater—both a woefully insufficient and overly optimistic remedy. On an even grimmer note, photographers also drank cyanide, either by accident or as suicide, which meant certain death.

Cyanide—painful, lethal, and surprisingly quotidian—was not the only darkroom risk. One article titled “Photographic Poisons and Their Antidotes” urged photographers to have “not only the antidotes to these poisons always in stock, but also…some effective emetic at hand where it can be procured at a minute’s notice.”

After cyanide, the article noted, poisons in use were bichloride of mercury, “the most violent of all those employed in photography”; nitrate of silver; and the various acids used in the darkroom, including nitric acid, sulfuric acid, and hydrochloric acid.

The suggested antidotes for bichloride of mercury included drinking an egg white; for nitrate of silver, sipping saltwater. For the darkroom acids, the home remedies included magnesium carbonate or pounded chalk dissolved in water. If that didn’t work, to prevent the throat closing the author suggested finding a surgeon to perform a tracheotomy.

Even the most safety-conscious photographers had to contend with the generally deleterious effects of poorly ventilated darkrooms.

For more than a decade, photographic annuals included a handy table of poisons and antidotes for photographers to paste up in their darkrooms. For pyrogallic acid, used as a photo developer, that table of antidotes starkly stated “no certain remedy. Speedy emetic desirable.”

One misguided photographer applied pyrogallic acid on a patch of eczema, believing it would help his skin; it resulted in an ulcer that took six weeks to heal. Another very unfortunate photographer accidentally drank pyrogallic acid, and died three days later.

Even the most safety-conscious photographers had to contend with the generally deleterious effects of poorly ventilated darkrooms. Beyond the terrible smell of collodion, the ether, alcohol, iodine, and bromine produced damaging vapors. Ammonia, if spilled in sufficient quantities, could cause “asphyxia,” one journal warned. (In the event of accidental swallowing, another journal proposed the following as an emetic: tickling the throat with a feather.)

Photo journals suggested maintaining a well-ventilated darkroom, but one photographer published an honest account of the nine-by-twelve-foot room he had claimed in his house, in which he covered up the window to exclude light (and fresh air). Inside, he wrote, “the air gets loaded with the smell of machine oil, albumen paper and old hypo, and it is sometimes just awful in there, even to me.”

______________________________

Reprinted from Flashes of Brilliance: The Genius of Early Photography and How It Transformed Art, Science, and History. Copyright (c) 2025 by Anika Burgess. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.