Slow books. Long-haulers. Glacial-pacers. Forever-endeavors. Determine the quickest, most efficient way of writing a book, and then do the opposite: That’s me. Besides sleeping, there is no activity to which I have devoted as many hours of my adulthood as researching and writing three of my five books. As writerly processes go, this one has zero professional benefits and can be murder on the ego, too. Nonetheless, I’m five years into the research of my fourth long-hauler that’s shaping up to be my slowest yet.

Article continues after advertisement

Why do I write these sorts of books, repeatedly?

Two reasons are universal to any writer who was neither born into nor married wealth: money and time. The three books that collectively occupied 30 years of my life have thus far earned $33,000 in advances and royalties from publishers. That’s their total sum, not their average. (Ego: slain.) That is why, prior to becoming a creative writing professor at age 40, I routinely quit jobs with health insurance, relinquished apartments, and migrated from one writing residency to the next, crashing on friends’ futons in between: because, lacking the money to buy it, the only way I could conjure time was by renouncing all other responsibilities. Living nomadically let me write my two “reasonable” books, that is: completed in respectable amounts of time (eight months for one; three years for the other) for confusingly higher payments (about $85,000 in advances and royalties, combined). I am, therefore, capable of speed. Unfortunately, it requires total self-abnegation plus mooching off everyone I know.

If you are so afflicted by time, money, and your own unique psychology that you too are contemplating a slow book, let me now stage an intervention by articulating three reasons to stop:

1. Your subject will change. I handed in my second long-hauler, All the Agents and Saints: Dispatches from the U.S. Borderlands, three weeks before Trump won his first presidency. Guess how many executive actions he took on its primary subject (immigration)? Wrong! It was 472. Seven years of investigative reporting became an instant artifact of the Obama Administration. To everyone out there attempting to write about anything involving the United States right now: I feel your ache.

2. Your characters will change. You know that person you admired so much when you met in, oh, 2016? The one who inspired you to write that book in the first place? What happens when you call them up in 2025 to let them know the book is (finally!) on its way and you just need to fact-check a few last things, only to learn they are no longer pursuing the same truth, ideology, sobriety, or marriage (in fact, they just filed for divorce last week) and they ask why you are casting them in literary amber?

3. Your ability to write about your subject and/or characters will change. I’ve counseled two friends through the utter despair of abandoning long-haulers for which they’d already received lucrative advances, and I’ve buried a friend who died before completing his own decades-long project, and I don’t know which fate I fear more.

We are not merely researching and writing the matter of our books here. We are researching and writing the matter of our lives. That is why we can and perhaps even should resist the capitalist imperative to rush.

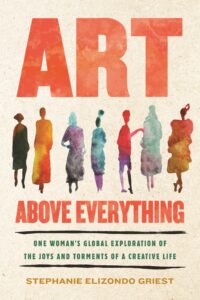

How are you feeling about your glacial-pacer now? If I haven’t convinced you to quit yet…. you just might be an art monk like me. Welcome to the monastery! My favorite realization while writing my latest long-hauler, Art Above Everything: One Woman’s Global Exploration of the Joys and Torments of a Creative Life, was that, however alone we may feel hunched in our writing cells, we are actually part of a global congregation of equally devoted painters and sculptors and dancers and actors and musicians from whom we can draw not just inspiration but also solace, strength, wisdom, and courage. Moreover, as we wander the dark corridors of our forever endeavors, we discover psychic matches to light our way. Here are two of mine for you to strike:

1. Pick a completion date for your project, no matter how arbitrary, including: I refuse to still be working on this when I’m ___ years old. Whatever that date, broadcast it widely, so folks hold you accountable. When it finally arrives, see if you have a good ending. Has something transformed? Have you? If not, that’s a legit reason for forging on. You can’t spend years of your life writing about something, only for its ending to suck. Sorry, but only an angel-screamer will do. Before picking another arbitrary date, though, try to discern if you have any agency over your idealized ending. If it requires received knowledge of any kind, particularly court cases, political decrees, or the whims of any heart besides your own, beware. It may not come.

While writing Mexican Enough, one of my two “reasonable” books, I literally typed: “Insert insight here: _____________” at key points throughout the manuscript. Not surprisingly, few deep thoughts materialized before my publisher’s arbitrary-yet-definitive deadline. That’s because I had allotted only three years for a) the experiencing of, and b) the writing/reflecting/fact-checking/revising of: moving to the land of my maternal ancestry (Mexico) and learning its language (after a childhood of being shamed by it) before traversing its countryside interviewing everyone whose path I crossed about their Mexicanidad (which I then tried to adopt myself) while Mexico was itself on the brink of profound change (descending into a narco-war that killed and/or disappeared hundreds of thousands of people). What I needed was time, preferably of the non-nomadic variety, yet I had no money to buy it. And so, I suppressed my inner Girl Scout-perfectionist-idealist, deleted every insight goes here, and published something I knew in my heart could have been improved. This is the main reason I write glacial-pacers: each one represents the summation of my ability. I hope never to publish anything less again.

2. Determine what “success” will mean for your book before writing it, then broadcast it widely, to keep your ambition in check. If money is part of that equation, you’re in luck. Simply set your dollar amount, tell your agent you won’t write the book for less, and then: don’t. Success!

If that feels like the literary equivalent of telling your obstetrician If my baby won’t grow up to attend Harvard, let’s not birth them at all, congratulations! You have reached the innermost chamber of the literary wing of the monastery. Here, we conceive of books as thought-children. Like the diapered variety, they are proof that we have lived. Not because of the publisher’s logo stamped on the cover, but because of what they contain within: the teachers we encountered, the places we travelled, the knowledge we cultivated, the worlds we envisioned, the memories we revisited, the ideas we formulated, the agony and ecstasy we experienced penning it all to paper, the courage we mustered to share it. We are not merely researching and writing the matter of our books here. We are researching and writing the matter of our lives. That is why we can and perhaps even should resist the capitalist imperative to rush.

The slow book project gives us something money never will, and that is the prolonged act of creating life-affirming experiences. Slow books also lead us to more merciful measures of success, such as: how much we savored the time we cultivated. Such as: the impact of our revelations—on our subjects, on our readers, on ourselves. Such as: the matches we shared with our fellow art monks along the way.

________________________________________

Art Above Everything by Stephanie Elizondo Griest is available via Beacon Press.