In the early aughts—when I was in high school—my friends and I often chose Claire’s as our meetup location at the mall. We perused the accessories and sometimes could even afford to buy a trendy charm bracelet or puka shell necklace. One humid summer night in Cleveland, a copper arm band caught my eye. It was the kind of thing I imagined Cleopatra might have worn, curled several times around the upper arm, each end adorned with the ruby-eyed head of a snake. The ornament looked out of place hanging from a shelf in Claire’s, as out of place as I felt standing there in a polo shirt and loose cargo shorts, gawking at it. I tried it on, walking around the store, glancing in every mirror. My friends were running late. After a few minutes I stood in front of where I’d found it, considering if I’d really wear it if I purchased it.

“It’s fine for you to try that on as long as you don’t buy it.” A saleswoman had crept up behind me. She was Black, with graying hair pulled back into a tight bun, and she wore stockings, and the sensible, kitten-heeled shoes of a woman who never missed her Sunday church service. I didn’t know her, and yet I knew her very well.

“I’m sorry?”

“You wouldn’t actually buy that. You’re not a girl; it’s not for you.”

She had clocked me.

“No, ma’am, I guess not.”

I typically felt invisible, but with one glance, one comment, this woman let me know that she could see me for what I was—and what I wasn’t.

I placed the arm band into her outstretched hand and rushed from the store, my eyes lowered to the ground as I frantically texted my friends to meet me elsewhere. I was angry and embarrassed, but mostly I felt exposed. I’d been standing by myself in a store meant for teenage girls in a suburban mall in middle America. I typically felt invisible, but with one glance, one comment, this woman let me know that she could see me for what I was—and what I wasn’t.

A year later, a friend and I visited a different mall, a fancier mall, one that didn’t even have a Claire’s. We walked around, he and I, deep in conversation about sexual identity and stereotypes, when he asked me quite calmly, if I had ever considered the idea that I might actually be a girl—one who’d simply been born into the wrong body.

I considered his question. His tone was gentle, but his query was sharp, pointed, and it lodged itself inside of me. I was aware of their existence—because of the T in the acronym LGBT, and because I’d seen episodes of The Nanny and Will and Grace—but trans people had always been, to me, more theoretical than real.

Being “trans” seemed an unthinkable way to move through the world. I was already Black, and gay, and the son of a well-known Baptist minister. I was a high-school senior who had somehow managed to survive at a deeply conservative all boys prep school. Soon I would be a freshman at a progressive liberal arts college outside Philadelphia. I had worked hard in school, convinced that leaving Cleveland and never looking back was the only answer if I wanted to live my best Black queer life. This college—a campus where The Princeton Review said it was easier to come out as queer than as a Republican—was my reward. I wanted to step into the freedom of the real world, and distance myself from the context in which I was raised. I was not looking for further marginalization.

I told my friend that I was not transgender, but his question punctured me like a bullet that wouldn’t, or couldn’t, be removed.

I first had the idea for an essay series centering trans and gender non-conforming writers of color in the fall of 2021. I had recently been named the Editor-in-chief of Electric Literature, a groundbreaking digital literary magazine with an annual readership of more than 3 million. A few months earlier, I’d publicly disclosed my identity as a trans woman, something I’d been preparing to do for two years in response to a question I’d been asking myself for sixteen. When I was named to this new role, I was widely celebrated as the first Black, openly transgender woman to helm a major literary publication.

Around this time, the comedian Dave Chappelle released a new Netflix special, The Closer, in which he pitted the Black community and the LGBTQ community against each other, arguing that queer white people are better off in contemporary American society than Black people and often participate in the racist marginalization of Black people. The role played by different marginalized groups in each other’s oppression deserves a richly considered and nuanced conversation, but instead, Chappelle completely erased the existence of those who live at the intersection of Black and queer identities.

Around this same time, Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie published an essay which doubled down on an evasive response she gave when asked whether or not a trans woman is a woman: “…My feeling is that trans women are trans women.” This puzzled me. As a woman who claims to be in alliance with the LGBTQ+ community, her choice to write the essay felt like an intentional anti-trans dog whistle to her global army of supporters, many of whom are self-identified terfs (trans-exclusionary radical feminists).

For all the dialogue surrounding trans identity, the loudest voices in this conversation were never trans people, and in particular, never trans people of color.

But Chappelle infuriated me. The popularity of his special, and the conversation it ignited, remained a major talking point in news media for weeks. Netflix defended the special, resulting in a walkout by their trans employees. Over weeks of social media and news media discourse, what I noticed was this: for all the dialogue surrounding trans identity, the loudest voices in this conversation were never trans people, and in particular, never trans people of color. We were the existential center of a cultural boiling point—and our voices were almost nowhere to be found.

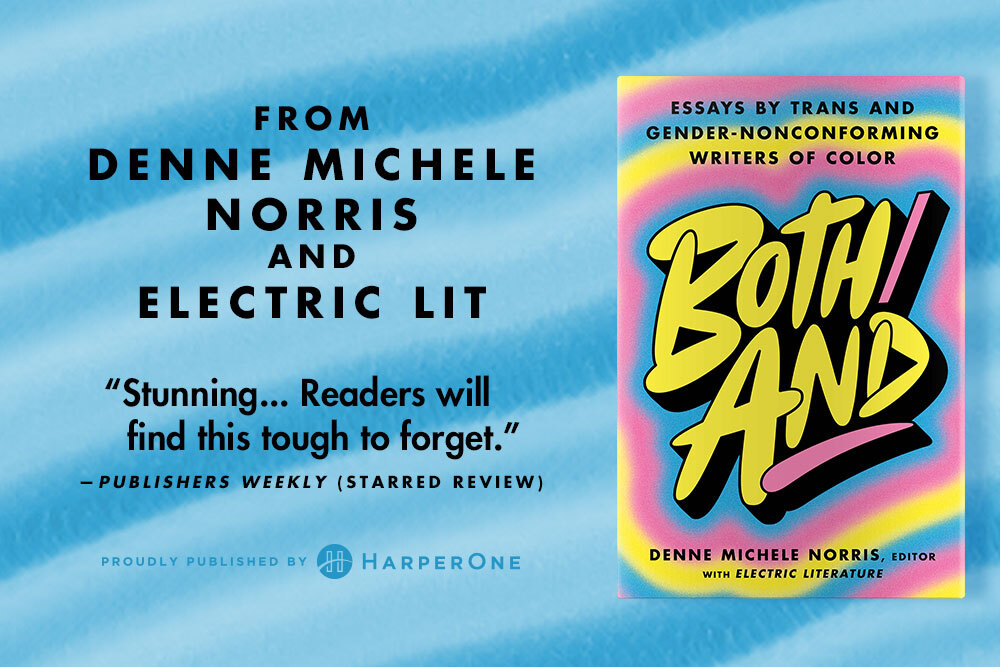

From my fury was born Both/And, a series of fifteen essays published online by Electric Literature, with the goal of elevating emerging trans and gender nonconforming writers of color to a national literary platform. But there was one key distinction—these writers would have the unique opportunity to be edited by a trans writer of color. Electric Literature quickly fundraised to support the series, meeting and then exceeding our goal in just one week, proving that writers and readers alike were hungry for these essays. The popularity of the series, which was published on electricliterature.com in 2023, as well as the ever-growing far-right political targeting of the LGBTQ+ community, further proves how necessary these essays are.

A few nights ago, Donald Trump won the 2024 presidential election, during which Republicans spent hundreds of millions of dollars on anti-trans ads. As I watched the results, my heart fell from my chest. I knew what was coming, and predictably, less than twelve hours later, I tuned into morning shows where I saw political pundits—from both parties—blaming the trans community for the election results. Early analysis saw folks saying that the Democratic party was out of touch with the majority of American voters, that it was too woke, that American families didn’t want grown men playing sports against little girls. The absurdity of that statement aside, I kept thinking to myself, But I’m an American voter, too.

What followed was a profound sense of displacement, politically speaking. While my values are progressive, I have always been a voter motivated by pragmatism and harm reduction. I was raised in a Black, middle class family of churchgoers by parents born between the silent and the baby boomer generations. I was raised to vote in every election. And I was raised to vote without attaching a grave sense of preciousness to that vote. It wasn’t necessary to agree with everything my chosen political candidate said, in part because voting wasn’t supposed to be the sum of my political engagement. It was a chess move, a means to an end, and it was the bare minimum. More simply put, I have always been a registered voter, and I have always voted for the Democratic ticket. Given my values, this means I have also, always, held a deep sense of frustration at the party’s continued pursuit of moderate white voters.

I have always worried that when it comes to policy, measures that affirmed and protected my existence would end up on the chopping block.

Being Black, and being queer, I have always worried that when it comes to policy, measures that affirmed and protected my existence would end up on the chopping block. And very often, that’s exactly what happened. But in recent years, public opinion has shifted. Marriage equality, for instance, has been legal for nearly a decade, and folks have largely realized that their heterosexual marriages were never in danger. Perhaps it was the optimism of youth, or the stability of democracy, but I never looked into the future fearing what it held for me, or my community. When faced with the possibility of a rebooted Trump administration, I felt strongly that Kamala Harris needed to win if I was to maintain any sense of safety.

Whenever progress is made, there’s corresponding backlash. Right now we live in a time of unprecedented targeting against the LGBTQ+ community, and yet we stand on the precipice of an even darker era. Being a writer, I turn to literature in times of darkness—the writing of it, and more importantly, the reading of it. In the face of a political class that, at best, hesitates to stand beside us, and at worst works to bring about our ruin, I introduce you to the brilliant writers in this anthology, all of whom live at the fraught intersection of race and gender identity.

Each of these essays is a wonder, something taken from the heart of its writer and flung, with delicious abandon, into this world. Each essay leaves an imprint, promising to reverberate inside the reader. There is Akwaeke Emezi, who meditates on what it means to be beautiful across gender, and Tanaïs, who writes about the fantasy of making feverish love to another femme, to mark the occasion of a landmark birthday. Meredith Talusan remembers a casual hookup that awakened the woman within, and Gabrielle Bellot travels to Hawaii with her wife, where the eruption of a volcano inspires her inner goddess. These are just a handful of the essays that turn their gaze inward, and backward, straddling—and sometimes weaving—what it means to be man or woman, masc or femme.

There are also essays that turn their gaze fearlessly forward, conjuring the sort of tender, loving future we so rarely get to live. Zeyn Joukhadar considers what it means to be part of a future their ancestors never lived to see. Kaia Ball dreams about their estranged father coming out as trans, and finding a way to accept them. Jonah Wu brings the reader along as he jumps from the proverbial cliff into the world of hormone replacement therapy, embracing a more masculine future. And A.L. Major considers the cost of creating the life, and family, of their choosing.

Historically, trans people have been forced to imagine, or conjure, representation of ourselves into existing narratives that never sought to include us, often using the stories and fictional lives of canonically cishet characters as foundations for possible trans stories. Both/And is unabashed in its portrayal of the fullness of our lives. These essays consider imagination and fantasy as real-world liberation, the heightened visibility and invisibility of trans bodies, trans joy, laughter and love, and trans rage, revenge, and loss.

My community is under vicious attack on every level, but we refuse to disappear, and I refuse to allow our stories, and our lives, to be erased.

At Electric Literature, we believe that literature has the power to shape public consciousness. Storytelling breaks down barriers in numerous ways; perhaps the most powerful being the building of empathy. My community is under vicious attack on every level, but we refuse to disappear, and I refuse to allow our stories, and our lives, to be erased. The time is now for trans and gender nonconforming writers of color to amplify our own voices on our own terms. While the culture is obsessed with us, that obsession has been weaponized in an effort to legislate us out of existence. But it simply won’t work because we’re already here. We’ve been here, telling our stories in our own words, our voices rising to the rafters, ringing so loud that we’re impossible to ignore.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.