I had never dreamed of writing about divas until I happened upon Maria by Callas (2017), a French documentary by Tom Volf, a filmmaker unknown to me. Of course, I knew about Callas and her epic tug of war with Jacqueline Kennedy, the most celebrated widow in the world, over the charms of shipping tycoon, Aristotle Onassis.

The widow won.

Callas lost her voice and retreated to her mausoleum-like apartment on the Avenue Georges Mandel in Paris’ posh sixteenth arrondissement. Director Pablo Larraín tried to recreate the last days of her life in the film Maria (2024), starring Angelina Jolie as the aging soprano. The film did not capture Maria at all.

Maria died a diva, broken but proud, with a dignity that Angelina Jolie never revealed for a moment. Perhaps it wasn’t her fault. Both the direction and the script were poor. And Pablo Larraín’s absent diva got me to think about what the characteristics of a diva were.

Beauty was a prerequisite—a deep, relentless, heartbreaking beauty. Maria Callas was not a diva at the beginning of her career. She weighed two hundred pounds. She had a heavy tread and a heavy voice. But in 1953, at the age of thirty, Maria saw Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday, and decided that she wanted to have Hepburn’s svelte look. Maria lost eighty pounds in a year, and suddenly with her big eyes and big nose she had the exotic look of a female pharaoh. Critics said her rib cage would be ruined and she would not be able to hold long breaths and would have to abandon half her repertoire.

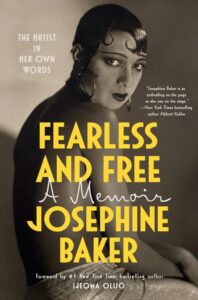

They were all wrong. Suddenly La Callas became a fashion icon. She was interviewed everywhere, courted everywhere. And Maria by Callas revealed the diva she had become and would remain for the rest of her life, even after she had lost her voice. Each step she took on stage during her glory years was like that of a lady panther. Her voice wobbled occasionally but could fly across three registers. She was nearsighted and had to memorize each stick of furniture and where it sat on stage. Every role she performed became definitive during her lifetime. She was the diva of divas. And the Callas I wrote about in Maria La Divina died abandoned and alone, but with the same Bulova watch at her side, a watch she had won in a singing contest when she was eight.

The diva must have great dignity, but also a tragic flaw. Maria was a tigress on stage, but she was helpless against Onassis’ constant scheming. He outmaneuvered Maria, left her for Jackie Kennedy, and lived to regret an unfortunate marriage, as Jackie outmaneuvered him.

There have been other divas, of course, and they make for excellent reading. Here are five of my favorite books about the lives of divas.

*

Joyce Carol Oates, Blonde

Joyce Carol Oates sees the Blonde, about the life of Norma Jeane Baker aka Marilyn Monroe, as her very own “Moby Dick,” as she grapples with the White Whale of American history, while the novel weaves across the twentieth century, with the reinvention of Jack Kennedy as the Prince and Joe DiMaggio, Norma Jeane’s second husband, as the Ex-Athlete, among a trove of other characters. There’s a rage in Oates as she relates how Norma Jeane was mistreated by powerful men, including Mr. Z, Darryl Zanuck, who rapes her during their first encounter and remains her studio boss throughout the early part of her career.

We can almost feel Oates inside Norma Jeane’s flesh, as if there were a kind of echolalia throughout the novel, a mixture of maddening voices that captures what is inside Norma Jeane’s head. And Oates has accomplished a miracle; she has made Marilyn a diva and an anti-diva at the same time, someone who ripped at her own fame.

When I recently asked Oates whether she felt that she had become Norma Jeane as she worked on the novel, she answered yes—“it was a gradual, then something like a total immersion for months of increasing intensity. I did feel this was the deeper, more inward & perhaps secret—certainly unarticulated—Norma Jeane that the world rarely saw . . . I had wanted to write about ‘Marilyn Monroe’ impacting strangers’ lives—having meaning to their lives while her own life was in free fall—the irony of being an Icon for others, while helpless & doomed herself.”

Allegra Kent, Once a Dancer

Allegra Kent is another example of a diva gone wild. “As a child,” she says in the first lines of her autobiography, Once a Dancer (1997), “I knew I had one great possession: my body. It was little and quick. I lived within it.” That body had a magical suppleness, a plasticity that was rarely seen in a dancer. And George Balanchine, the artistic director of the New York City Ballet, was one of the first to recognize Allegra’s gifts. She joined the company at 15 in 1953 and was promoted to principal dancer—prima ballerina—before she was twenty.

Balanchine was adamant about three things, particularly when they concerned his prima ballerinas, telling Allegra that a prima should avoid “getting married, having children, and dancing ‘expressively’—and he was harsh in his enforcement of this code with everyone except me.”

Allegra was Balanchine’s wild child. She married photographer Bert Stern when she was twenty-one and had three children before she was thirty. For any other dancer this would have been a form of suicide, but Allegra loved being pregnant and “had the irresistible urge to look at my new body all the time.”

I remember seeing her in Bugaku with my own favorite male dancer, Edward Villella. The ballet concerns a Japanese ritual that is a thousand years old—it is an arranged sexual encounter between a samurai warrior and a woman of royal blood. “When my attenants removed my train in preparation for the conjugal pas de deux, I always felt naked, even though I was lightly covered in a costume.”

There is a dreamlike quality to her dancing, as her body intertwines with Villella’s. She seems possessed, as if her limbs had a life of their own. She climbs on Villella; he could be a mountain of flesh. That moment of their consummation still haunts me, and it happened more than sixty years ago. Of course, Mr. B. punished Allegra after her third child. He created no more ballets for her. “I had lost the Atlantic Ocean,” she lamented. But he always paid her a salary, even when she danced only once or twice a year. That was the dilemma of a diva. Her wildness emboldened her on stage. “Only in dance did I assert myself and assume my real nature, just as I had as a child.”

Annie Zaleski, Lady Gaga: Applause

Lady Gaga never stands in one place. She’s always on the move. She’s much more intelligent than most pop artists. She sings, she dances, she writes songs, models clothes, and she acts, each with a novel twist. We can’t take our eyes off her. She casts us in a hypnotic spell. She can sing hard rock and then do ballads with Tony Bennett.

Lady Gaga is a singer-entrepreneur, who inherited some of her skills from her parents, both of whom had businesses of their own. Born Stefani Germanotta on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, she would explode on the rock scene as a most unusual icon, according to Zaleski. She suffered her own misfortunes, was taunted by her fellow high school students as a misfit and was sexually assaulted by her first producer when she was only nineteen. But Stefani survived and morphed into Lady Gaga.

“I want people to feel invaded when I sing. It’s very confrontational.” That’s one of the reasons she wears outrageous costumes whenever she performs, like a rhino horn on her forehead, or an outfit that turns her into an Alice in Wonderland teacup. There’s also another side to her art—she’s never confrontational with her fans. “They are the kings. They are the queens. They write the history of the kingdom, while I am something of a devoted jester.”

Josephine Baker, Fearless and Free

The daughter of a washerwoman, Josephine Baker was born in St. Louis on June 3, 1906. Her own father was a mystery to her, and it’s unclear whether he was Black or white. She left school when she was eight to work as a nursemaid to the infant of a rich “American lady.” At fourteen she ran off to Philadelphia to join the chorus line of a Black and white revue. By the time she was sixteen she was in Broadway’s first all-Black musical, Shuffle Along. Feeling isolated and alone, she abandoned America and landed in Paris when she was nineteen, taking part in La Revue Nègre.

Baker felt welcomed from the moment she arrived and appeared on stage. “Paris adopted me from the very first night.” She also understood the racism that was inherent in her success. “People think I’ve come straight out of the wilderness. . . . White imagination is something else” when it involved a young Black American dancer doing the Charleston while skimpily clad.

In 1926 she met French journalist Marcel Sauvage and decided to do a memoir based on a series of interviews. Those interviews lasted twenty years and resulted in Fearless and Free, first published in 1949. Sauvage understood the complexity of Josephine’s situation in France. Her dancing “pitted instinct against civilization in a style that was caricatured yet powerful. It was said that a touch of hate was also present—a desire for revenge, perhaps, legitimate pride in pure animality—all quickly concealed behind parody and funny faces.”

Josephine was famous for her funny faces; she loved to clown, but I suspect that her “pure animality” was Sauvage’s own invention. No matter. She triumphed, had her own chateau with a greenhouse and a menagerie of pet snakes. She trekked across Paris feeding the poor. When she performed in the capitals of Europe, she was often shunned as the Black Demon who liked to wear a banana belt and dance “like the devil.” Yet she packed every theater and music hall. Kings and queens came to see her dance.

She was now the most celebrated music hall artist in all of Europe. But World War II caused a change in her life that was both drastic and dramatic. She wouldn’t perform in Occupied France, but she became a secret agent for both the French and British intelligence services.

After the war she would have a long sojourn in the United States. But she had no illusions about the country she had left behind. America had become “a world of lost people. Nothing but money counts.” The diva returned to Europe, where she retired to a chateau in the south of France with her Rainbow Tribe of twelve abandoned children from all over the world—still the diva, irascible and funny, with a family all her own.

Marlon Brando with Robert Lindsey, Songs My Mother Taught Me

Brando’s autobiography, Songs My Mother Taught Me (1994), written with Robert Lindsey, reads like an endless rant against Hollywood, against the racism of America, and against cinema itself, with a few insights thrown in here and there.

“I laugh at people who call moviemaking an art and actors ‘artists.’ Rembrandt, Beethoven, Shakespeare and Rodin were artists; actors are worker ants in a business and they toil for money.” Shakespeare also toiled for money, and Brando is much more than a worker ant in On the Waterfront (1954), where, with the force of his craft and his intuition, he turns the portrait of a washed-up prize fighter into a heartbreaking piece of poetry. “Nobody creates a character but an actor,” he would later admit. “I play the role. . . . He’s my creation.”

Nowhere is this more evident than in The Godfather (1972), where Brando redefines the role of Don Vito Corleone, “softens” him so that he has even more menace. Paramount didn’t want him to play the godfather; he was no longer a big star at forty-seven; his latest films were all flops. But he stuck wads of Kleenex in his cheeks and auditioned for the part. The bigwigs at Paramount reluctantly accepted him at a very reduced salary. Brando, the owner of an atoll in Tahiti, where his family dwelled, had become the beggar of Hollywood, who had to feed on crumbs. But his rendering of Don Corleone, who did his own slow, silent dance, unlike any other Mafia chief, overwhelmed the screen, and The Godfather was the biggest hit Hollywood had ever had up to that time, thanks to the Kleenex and cotton balls in Brando’s cheeks.

I was drawn to Brando from his very first performance, in The Men (1950), where he plays a muscular paraplegic in a military hospital. “Brando wasn’t safe, wasn’t predictable, wasn’t imprisoned by any frame,” as I wrote fifty years later in the New York Times. “It was impossible to tell what he would do next.” He was larger than any narrative he was in. I remember being bored when Brando wasn’t on the screen, feeling sick in a sea of dead space. On the Waterfront, I told my high school class, is about Brando and the nothingness we have when we’re deprived of him.

The last film of his where he imposed his brilliance upon the screen was Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris (1972). Bertolucci told him to essentially play himself, as if the recently widowed Paul “were an autobiographical mirror of me.” Brando revealed the hurt of his “lonely, friendless” childhood in Hamlet-like soliloquies. It took its toll. Last Tango left him feeling depleted. “I decided that I wasn’t ever again going to destroy myself emotionally to make a movie.” From then on he played one buffoon after another. Brando broke himself for an art he wouldn’t even recognize as his own. That’s the fate of a diva.

__________________________________

Maria La Divina by Jerome Charyn is available from Bellevue Press.