March 31, 2025, 2:55pm

Spring is soiree season. You heard it here first. And a few recent books—like Aria Aber’s novel Good Girl, or Emily Witt’s investigative memoir, Health and Safety—have revived an age-old character about which the soiree orbits. The party girl.

I don’t mean the term diminutively, or as gender-bound. The party girl in literature is an arch-type, defined only by a love for going out. We might trace their roots to Edwardian gold-diggers, but they’re just about everywhere else these days, too. Falling down a K-hole in Bushwick or Berlin. Or sneaking past security in the Hamptons. Personally? I’ve missed those scrappy ways.

So in that springly spirit, here’s a taxonomy of the five kinds of party girls you’ll find in literature. Pick your player, take a recommendation, then get back to planning your night.

L’enfants terrible

Epitomized by Eloise, this smallest of the party girls is a force of chaotic-evil. She wants it her way or the highway. Not yet frightened by the concept of mortality, she is prone to risky behavior. On the dark end of the spectrum she is truly wild, like the anti-hero of the late Jade Sharma’s Problems. You love her even if she destroys your things, and worry the rest of the time.

Her next read: Cynthia Weiner’s A Gorgeous Excitement. This debut novel, set in an opulent 80s New York, follows a young woman down a drug-hazy rabbit hole.

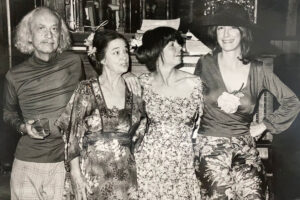

The Scenesters

Often found in California, the scenester is a party girl whose social life is circumscribed by, well, a scene. (Or an industry. The industry, we may as well say.) She’s particular. And possibly conniving. Either ambition or loyalty tie her to a specific community. This floppy category includes the groupies described in Pamela Des Barres’ I’m With the Band, and the assorted Hollywood hangers-on best depicted in Eve Babitz’s canon. On the opposite coast, you’ll find the scenester in the models and magazine milieus of Mary Gaitskill stories. And in Rona Jaffe, Dawn Powell, and Jacqueline Susann books before that.

Their next read: Hannah Levene’s Greasepaint. This experimental novel about the mid-century butch bar scene closely observes a tight scene.

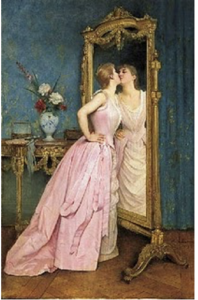

The In-It-To-Win-Its

Lydia Bennet is the queen of these jokers, who will come to your ball with an eye to conquer. Though perhaps a little unpolished, a little uncouth—see also Undine Spragg of The Custom of the Country—this gal loves a classy time and covets the spouse who can ensure she’ll always have one. Ambition is often at odds with affect in this case. But even though she might create a scene at the soiree, the In-it-to-win-it has a genuine affection for the trappings of wealth that her reluctant hosts so often lack. Which will either be her downfall, or her greatest asset. Either way? Game on.

Their next read: Jessie Redmon Fauset’s Plum Bun. Recently reissued with a forward by Morgan Jerkins, this Harlem Renaissance classic follows Angela, a Black woman painter who passes into a world of artsy elites in Jazz Age Manhattan.

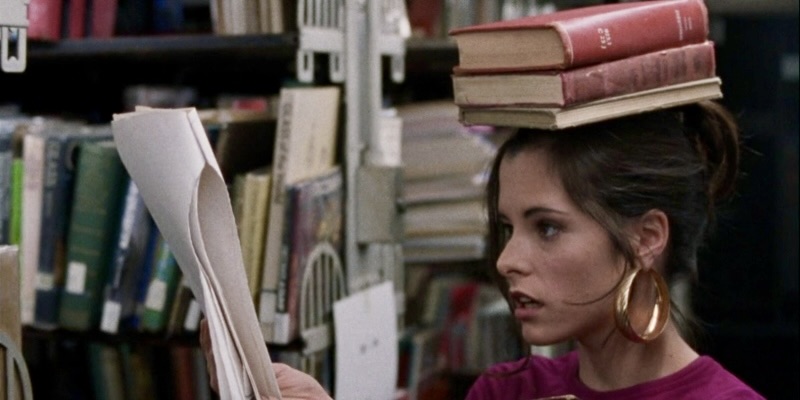

The Artful Dodgers

Similar to the in-it-to-win-it in that she’s never met a gown she didn’t like, the artful dodger is a penniless person who loves a high society event. But she’s shrewder when it comes to getting past the red rope. And being less inclined to classism, is often just as comfortable at a gross warehouse party. Champagne and trust funds are nice, but interesting conversation holds the key to her heart.

Her contemporary avatar is Isa Epley, of Marlowe Granados’ Happy Hour. But antecedents include Lorelei Lee of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Sally Bowles of The Berlin Stories, Doris of The Artificial Silk Girl, and—debatably, for striver reasons—Capote’s Holly Golightly.

Their next read: Brontez Purnell’s 100 Boyfriends. You’ll notice again the trap I’ve written myself into, with this gendered language. But this hilarious, consuming chronicle of a queer scene is chock full of dodgers.

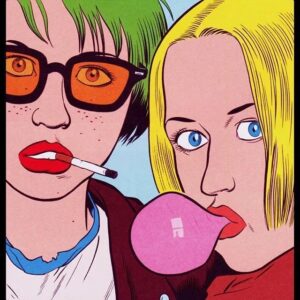

The Curious Cats

This type accepts any stranger’s invitation on a whim. Boredom is their animus. Often but not always, this guest travels in a security blanket set. (See Enid and Rebecca, of Daniel Clowes’ Ghost World. Or Jane Bowles’ Two Serious Ladies. Or Mimi Smithers, the modern day Mrs. Bovary behind Robert Plunket’s Love Junkie.) Yet she can also manifest adventures alone, like Yasmin Zaher’s untitled heroine in The Coin. In any case? Here be a drifter, off to the see the world.

Their next read: Sheena Patel’s I’m a Fan. This hypnotically weird novel follows an unnamed narrator with an internet stalking problem right down the rabbit-hole.

The Independent Icons

The iconic party person is defined by a breezy confidence on top of a lust for life. Whether convening a salon or flitting between A-list events, the icon stays entertained and entertaining. Like the legendary author and party guest Zora Neale Hurston, she loves herself when she is laughing. Other antecedents from real and fake life include Cookie Mueller, Sally Jay Gorce of Elaine Dundy’s The Dud Avocado, and Andrea Bern of Jami Attenberg’s All Grown Up.

The icons have a dependent sub-category—the hostess with the mostest. Though they apparently need partners to complete them, Laurie Colwin’s happy heroes, with their meticulous dinner party menus, can be found in their ranks. (But so can Auntie Mame.)

Their next read: Recollections of My Life as a Woman: The New York Years, by Diane Di Prima. This memoir comes from an ur-bohemian and true mid-century icon.