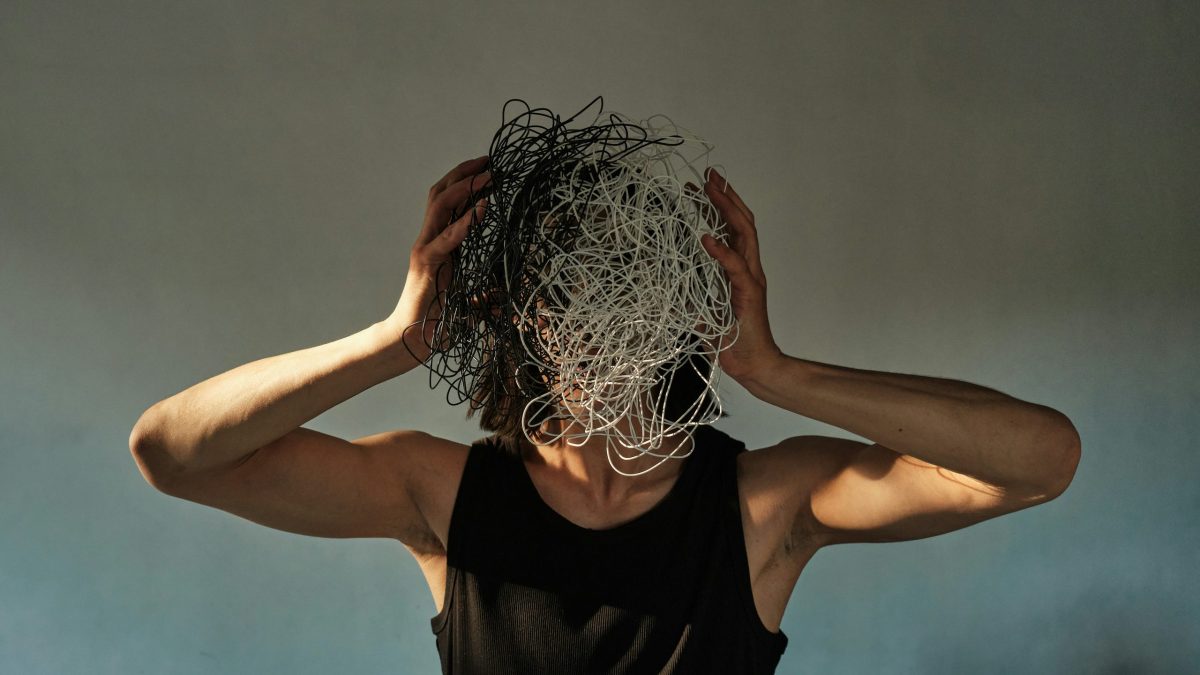

Halfway through my idea, an axe came flying to chop it apart. This happened every day, all day. I could not think!

The human mind wants to flow in long lines, spin up stories, hatch plans, and solve problems. If thoughts are trains, then mine were a wreck in a desert landscape, keeled over on its side. Wandering around the mess I was heartbroken, toes banging against a piece of bent metal here, remains of an armrest there. Hoping to get sharp again I kept pounding coffee and RedBull. But my mind just looped, like a line of broken code firing up and never executing. This was what the medication did: olanzapine is a substance similar to antihistamines, the drowsy allergy relief. The difference is that it never put me to sleep. It just got me part of the way there, when thoughts become vapors. On the outside, I gave the appearance of being calm and at peace. But inside I was browbeaten, stuck, grieving my once free thoughts.

“You look happy,” says a psychiatrist to a woman in Shulamith Firestone’s book Airless Spaces, a 1998 collection of portrait sketches of women at the New York hospital. The scene is a soup kitchen Christmas function. A mental patient shows up after a year of living alone. Her affect is flat. She’s heavily medicated.

“She made a wry face: ‘Not quite.’ He tried again: ‘Content, at least?’ She shook her head no. He finally settled on ‘Stabilized?’

‘Stabilized, yes,’ she granted.”

From the story “Stabilized, yes.”

To stabilize means to cause something to become fixed and stop changing. It’s cruel to do this to a human mind. The mind wants to move around, shape-shift, spiral, explode. The word “stabilize” comes from carceral psychiatry and the context of punishment and enforcement. But over time, it has become part of everyday conversations about care,, support, kindness and wellbeing. It has entered the context of family, love, friendships and work relationships, where it is squarely misplaced. Once, a mentor I had in graduate school told me about a student who used to be troubled and overdramatic, “but now on medication, she’s really stabilized.”

I froze. I knew this was supposed to be a good news story and I was expected to applaud it.

“I was the one who took her to the psych ward.” My mentor’s voice held the satisfaction of the end of a fairy tale: “I got her help.”

“Did you go visit her?”

“No,” my mentor gazed quizzically into the middle distance. “I didn’t want to intrude, and she never contacted me afterwards. Not even to say thanks!”

It seems like a coin with three sides, on which the first-person experience does not match with its medical record, does not match with the appearance to an outside observer. The three threads–self, science, and society–are knotted in a web of mutual misunderstanding, deception and misprision.

We’ve all heard the story about a “chemical imbalance in the brain” that medications are going to correct. But when considering the first-hand accounts of the people who’ve actually taken the medications, we may hear that chemical peace feels oppressive, stabilization can be like a chokehold, and the promise of balance is just a lie. Meanwhile, there’s adverse effects like drowsiness, lethargy, and impacts on heart, liver, and hormonal health. Finally, there is one more paradox: To say the meds don’t work, or that they’re bad, is to be mentally ill. The Diagnostic-Statistical Manual (DSM) of psychiatric disorders has that baked into the list of symptoms, so to have first-hand experience will lessen, not strengthen, your authority on the subject. I used to butt my head against this stone wall of barmy logic. What world is this?

When I heard about the memoir Unshrunk by Laura Delano, I was excited. With a subtitle like “A Story of Psychiatric Treatment Resistance,” I hoped it would go into that dark and tense field of when the meds don’t work, the meds are bad, and the more you say it, the more they want you to take them.

Unshrunk maps that under-examined experience through the auto-anthropology of Laura, a young woman from a super well-heeled background (New York debutante balls!) whose early brush with mood swings at thirteen lands her the first appointment with a therapist, that will turn out to be the first of hundreds more.

The three threads–self, science, and society–are knotted in a web of mutual misunderstanding, deception and misprision.

Delano, who is in her early forties today, writes in her preface that she spent the best part of her teens and twenties as “a professional psychiatric patient” (her words—I’ll refer to the author as Delano, and the protagonist of the memoir as Laura). No expense was spared to give Laura the best of everything, especially when it came to medical and mental health care. She got therapist after therapist, medication after medication. To no avail.

Laura studies at Harvard, but has to miss a lot of school. She does not learn or grow like other college students. No dramatic broadening of horizons takes place, no academic romance with a new subject. There’s no “coming of age” like in Elif Batuman’s The Idiot, nor even (not really) any of the sexy, messed-up stuff from Elizabeth Wurtzel’s Prozac Nation. Despite all that Harvard can offer young people, Laura fails to plan a career, let alone find her calling. After college she’s adrift and hops between therapy appointments, group sessions, treatment centers, and sundry social gatherings where she cannot talk about how she’s really doing, nor share the experiences that constitute her daily life. Increasing differences isolate Laura from the rest of her cohort, who are consumed with talk of internships, jobs, weddings, births, the property ladder; here, Laura’s life fades in comparison, and stays hidden behind a fence of shame and internalized ableism.

In recent years, the memoir market has seen many mental-health memoirs that resolve in redemption through therapy, or are built as tales of salvation-is-a-pill. By contrast, Delano’s Unshrunk takes a resolute stance against that trend. Unshrunk is one of the first, if not the first, traditionally published memoirs that explicitly writes back to the institutions of therapy, psychiatry, pharmaceuticals, and the pillars of what we think is a good family: so concerned with their daughter’s demeanor and appearances that they bankrolled an experience of over-medication, in what some might argue is a subtle form of gender-based violence.

It’s one of society’s many injustices that those who most urgently need mental health care–often unhoused, middle-aged, Black men–are denied access to the most basic services, while others—young white women from wealthy backgrounds—whose needs are less urgent, receive it in overabundance, to the point of it being counterproductive. Laura’s medications beget side effects, creating the need for more medications, begetting more side effects. Meanwhile, the insurance keeps paying, and everything snowballs.

Blown up to the scale of a cultural practice in North America, this dynamic has led to the creation of the “rich, overmedicated daughter” cultural phenomenon: a growing population of young women with multiple health issues and diminished autonomy. These young women bear the brunt of the medications’ side effects, which can include thyroid, kidney, liver, skin, and cardiovascular illness, cognitive impairment, stunted emotional growth, as well as professional, educational, and social limitations.

She got therapist after therapist, medication after medication. To no avail.

Laura’s story is part of a bigger picture. Her memoir follows in the celebrity footsteps of recent books by Paris Hilton and Britney Spears: Paris (2023) tells the story of Hilton’s ordeal in an institution for troubled teens, a place she describes as being somewhere between a boarding school, a prison, and an old-fashioned reformatory. Her handlers were intent on breaking her spirit, so that she would be “fixed” once and for all, and stop embarrassing the conservative Hilton family. Meanwhile, in the highly publicized case of Britney Spears, the singer received psychiatric treatments at the behest of her father, who engaged the American court system to extend his legal authority over her into adulthood.

Spears’ memoir exposes the legislative and social structures that enabled her entrapment–the mental health conservatorship, the tabloid press and its hostile coverage of her quarter-life crisis, misogyny in the music industry–and how tricky it was to detangle herself from these intercogged and combined locks.

“My world didn’t allow me to be an adult,” Spears writes, and: “The woman in me was pushed down for a long time. They wanted me to be wild onstage, the way they told me to be, and to be a robot the rest of the time.” (The Woman in Me, 2023)

It resonates deeply with a quote from Delano’s Unshrunk: “I was beginning to see my psychiatric medications more clearly for what they were,” she writes: “instruments of behavior control wielded upon me by professionals who saw it as their right to decide what went in my body. It was a right I’d once afforded them, but not anymore.”

Fueling all three women’s narratives are serious allegations of autocratic cultural practices in America: consent-violating paternalistic and socially malign customs that particularly affect women, especially in situations where money is involved.

The climax of Unshrunk is when Laura quits her medications, and then fires her therapists one by one. Laura comes to realize that the medication she took stopped her from feeling and thinking through “the deeper existential questions [she] was grappling with—ones about identity, performance, meaning, purpose, womanhood, body, and self.” Once aware of the damage done, Laura begins her journey of making up for her years of stalled development, missed milestones, and stifled personal growth. A cloud of brain fog lifts, the tomb under her feet cracks—she can breathe, expand, take up space. She becomes “unshrunk.”

One of Unshrunk’s most interesting sections is precisely the story of how Laura went off her meds. It’s a personal experience report of dramatic withdrawal, with horrific symptoms that encompass sensory disturbances, bodily, mental, and neurological dysfunctions, and an astronomical level of brain noise. The symptoms of psych med withdrawal are so severe, they include difficulties staying oriented, out-of-body sensations, mood swings, sleep issues, disruptions to normal thought processes. All of these are apt to bring on strange behavior in the person experiencing them, and produce symptoms that strongly resemble a psychotic break or serious mental illness like schizophrenia. They may even resemble mental illness more so than mental illness itself. Thus, for many people who’ve tried to withdraw from psych meds, these symptoms can become an invitation to say: “See, there. You have a mental illness. You need to get back on your meds!”

But that’s not right. Withdrawal is a different beast, biologically and chemically speaking. Delano’s book does a good job of explaining the difference, and really drills down on the bio-weapon that psychiatric medications are, focusing on their internal and endocrinological agency. She introduces concepts like homeostasis and iatrogenesis to dig deep and long into the physiology and biology of what happens when psychiatric medications enter and exit the mix of our bloodstream. (Spoiler alert: it is much, much more complex and all-encompassing than “a chemical imbalance in the brain”). Delano’s self-report of the weirdness, considerable pain, and bold-headedness it took to persevere in the face of lacking community support to wean herself off psychiatric drugs doubles up as a practical resource for people in the same predicament.

A few news pieces in recent years have noted that it’s notoriously hard to quit psychiatric medications. Some articles have spread the latest insight on how best to do it: “do it very slowly.” This conjures up the image of a slow and plodding procedure, assuming buy-in from the community and a sympathetic prescribing doctor who wants to help with the project–which it can be impossible to get.

A cloud of brain fog lifts, the tomb under her feet cracks—she can breathe, expand, take up space.

But let’s say that the first gigantic hurdle has been cleared. The medical aspect of the procedure is an equally tall order. The drugs are powerful, ridiculously so, even though our modern world seems to have forgotten that. But dip into their history and at the beginning, the clue was in the name: Thorazine. This early antipsychotic (developed from the 1930s and brought to market in the ‘50s) was named after Thor, the Norse thunder-and-hammer god. It was believed that Thorazine would be “a hammer” to the walls of insane asylums. It was such a strong sedative, it calmed even the most violent patient right down, without nevertheless putting them to sleep. This technology enabled a mass exodus of asylum patients, and their diaspora. Free to go home, some ended up in jail. Many more went on to live alone, shunned by former friends and family, like the woman in Firestone’s Airless Spaces. They took the asylum with them—orally, nano-technologically, delivered through the blood-brain barrier in pill form or as monthly injections. One might say that psychiatric medications installed the mental asylum at the molecular level, in chemical form, as an edible asylum if you will.

Today, the drugs’ Thoric strength is seldom remembered. Prescribing doctors rather emphasize that the newer generation of pills is easier to swallow. The patients’ jury is still out on whether that is true. Regardless, doctors now prescribe antipsychotics to all kinds of people for all sorts of conditions. Trending towards an aesthetics of cosmetic and elective pharmacology, psychiatry seems increasingly dedicated to preserving sameness, padding and blocking out anything that could be remotely ugly, uncomfortable, or unpredictable—and using the big guns to do so. The result is a growing base of people, like Laura, for whom the medication is wildly overcorrecting, and creates a “botoxed” inner self that is so motionless it has no wrinkles, but also, no life.

To make matters worse, with the rise of telemedicine and increasingly doing away with face-to-face consultations, especially in the mental health space, it looks as though in the future it’s going to become harder, not easier, to go off-script. When the doctor from the iPad only asks questions from a script written by AI, which was trained on centuries of hateful theory, could it be that we’re going back in time, not forward? This kind of thing keeps me up at night.

Our pharmaco-asylumian narratives stand for a secured, fixed, and immobilized state of order—especially for girls—not for disorder, nor dynamism, explosiveness, nor any kind of shape-shifting, transitional state outside of the sane/insane binary, nor for states that may be indecipherable, illegible, mixed-up, nor for any form of psychic entropy, chaos, change, self-divestment, nor spontaneous growth… The list goes on.

As the machine learning models are trained to know and perpetuate the abysmal status quo in mental health care, I often have dystopian visions of everyone I know lining up to get onboard a never-ending marble run of repeat prescriptions, until one day we’ll all be living in the edible asylum forever. So, before that can happen, we need to talk about mental illness as a two-way street, not a one-way destiny. When it comes to medications, we need to talk about the off-ramp, not just the on-ramp, and not just about prescriptions, but also de-prescriptions. Most of all, we need to come off the negative “stabilization” trip and prioritize becoming, growth, optimism, possibility, enablement, learning, revelation, nurture, connection, discovery, transformation and rebirth. Personally, I believe all of those things are possible and achievable for all of us, and I think Laura’s story and Unshrunk are a piece of living proof that it can work… and just how difficult it is.

The drugs are powerful, ridiculously so, even though our modern world seems to have forgotten that.

Delano’s work forges a path of emotional growth and possibility, despite how rough the medication withdrawal is and despite the bridges that had to burn as a result of her decision. Sitting with the unpleasantness, and pushing for change, she has emerged from her quest clenching a compilation of useful resources on what we know about psych med withdrawal—and how much we don’t. She highlights how no drug manufacturer ever ordered a trial to find out how to safely get patients off their psychiatric medications. Delano’s quick dive into (publicly available, but seldom scrutinized) clinical trial information, turns up that the drugs were trialed for just four to eight weeks before they went to market. No pharmaceutical lab or medical research facility has documented what happens to people after one, two, five, or ten years of constant psychiatric medication use. This means that next to nothing is known officially about the impacts of long-term use. What there is instead, however, is plenty of so-called unofficial knowledge: consumer-led knowledge bases, patient-led initiatives, that collect oral and anecdotal evidence, creating a preponderance of community-owned knowledge. Delano’s book points those who are interested in the right direction so they can learn more.

It’s certainly sobering to note that the scientific and medical literature has never thought this knowledge worth having, or worth producing an answer to the question of how modern psychiatric medications affect our brains and bodies when taken in the long term. But, for those who do wish to inquire, I guess a great way to find out might be to go and ask your local wealthy blonde girl. She might know.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.