On a cold evening in November 1988, a crowd was assembling outside a nondescript loft building in New York’s SoHo district. By 7:30, the line of people waiting to get into the Dia Art Foundation at 155 Mercer Street was snaking down to the corner and up Prince Street. There was a buzz of excitement as friends and acquaintances recognized one another, and casual passersby wondered what it was all about. In fact, the crowd was gathered for a reading by James Schuyler, a reclusive sixty-five-year-old poet who had never read in public before.

Article continues after advertisement

A hired town car pulled up in front of the building, and the slow-moving figure of the poet emerged, dressed in khaki slacks, a tweed jacket over a dark sweater, accompanied by his friends the painter Darragh Park, a tall, slim, strikingly handsome man with a mane of silver hair, and the editor Raymond Foye, curly-haired and boyish.

When the doors opened, the ground-floor space quickly filled to capacity. Folding chairs on a wooden platform provided slightly raised seating, with standees lining the back of the room. At the front a simple wooden table and chair were set before a plain blue backdrop. Looking around, members of the audience took stock of themselves, aware they were taking part in something special. The poet Peter Gizzi was struck by the diversity of listeners from across the city’s cultural spectrum: “The uptown poets and the downtown poets, the New Yorker poets, the staple magazine poets were there. Editors of big magazines, big presses, little presses were there. Abstract painters, figural painters, composers, language poets . . . every clan came out to hear him.”

There was a mood of expectancy mingled with apprehension, and a sense of the audience holding its collective breath.

After a brief welcome by Dia’s director, Charles Wright, the poet John Ashbery introduced Schuyler, calling him a friend of such long standing and intimacy that “asking advice from him is only a step away from consulting oneself,” and praised his work for being “written in what Marianne Moore calls plain American which cats and dogs can read. He makes sense, dammit, and manages to do so without falsifying or simplifying.”

The reading that followed has entered the annals of New York poetry lore. Many in the audience knew of Schuyler’s reclusive nature, which had prevented him from reading in public before, and his long history of mental illness, and some had heard tales of wildly eccentric behavior in his past. There was a mood of expectancy mingled with apprehension, and a sense of the audience holding its collective breath. Schuyler was impassive and outwardly calm, but in his very calm projected a certain vulnerability. He had been nervous about the reading beforehand and had been prescribed a beta blocker by his psychiatrist. “When about to enter a tumbrel, always take a beta blocker!” he wrote to a friend.

As Schuyler settled himself with his newly published book Selected Poems in front of him, put on his reading glasses, and took a drink of water, the painter Duncan Hannah recalled the room growing “dim, hushed, respectful,” with a feeling of “everyone pulling for Jimmy.”

“Past is past, and if one / remembers what one meant / to do and never did, is / not to have thought to do / enough?” Schuyler began with his first published poem, “Salute.” With this short poem, spoken in his deep, slow, and deliberate voice, with a very slightly “blurred” or “thick” sound, due perhaps to his false teeth or to years of taking antidepressant medications, Schuyler put to rest any doubts about his ability to read effectively. The poem itself, with its evocation of past expectations and present quiet resignation, seemed to encompass the room, the listeners, the poet, and the occasion in a circle of timelessness.

But it was with the third poem he read, the relatively long and discursive “Empathy and New Year,” that he hit his stride. Written at the turn of the year from 1967 to 1968 while living with the Fairfield Porter family on Long Island, the poem is quintessential Schuyler, interweaving immediate sensual responses to weather and daily events with witty asides and reflections. When he read the lines “It’s a shame / expectations are / so often to be counted on,” there was laughter from the room, which clearly delighted Schuyler, and he chuckled along in response. This happened again throughout the reading: whenever there was audience laughter, Schuyler quietly joined in. When he came to the end of “Empathy and New Year,” there was applause, the first poem to be followed by audience applause, but not the last.

“The acclaim was his due and he knew it. It was a great moment.”

As it became clear that Schuyler read very well indeed, both the crowd and Schuyler relaxed into enjoyment and appreciative concentration. The painter Trevor Winkfield, a longtime friend, recalled “everyone being ‘rapt’ as Jimmy read—we wanted to capture his every word, not miss a thing. The sense of [the] historic even was . . . very palpable. And Jimmy, I thought, read very well, very plain-spoken, like a truck driver giving traffic directions, no affectations or acting whatsoever.” The poet and publisher Geoffrey Young also approved of the way Schuyler read “with no ornament, no dramatic effect, just unadorned directness.” Douglas Crase recalled that once the reading had begun, “there was also the assurance of our poet’s deep voice as he read, he who was supposed to be so nervous.”

To Eileen Myles, “Everybody on the planet was there and everybody was so happy and I just feel like I had never seen an event in New York like that. There was no animosity, it was all like openness, we were all there for something that we had never had before and it was very exciting.”

When he came to the end of the forty-five-minute reading—all too soon—there was extended applause, which seemed to go on for several minutes. It started enthusiastically enough, but instead of tapering off after the expected few seconds, it went on, and on, and became self-perpetuating as people realized that it was lasting longer than usual and as a result continued it. Crase recalled, “Most vividly I remember the contented expression on his face when the audience burst into applause at the end, and how he kept us clapping by waiting a long time before he moved his books and signaled that we could shift our attention and break the spell. The acclaim was his due and he knew it. It was a great moment.” As Myles put it, “And then that famous applause that just didn’t end and that was so awkward and so beautiful. And Jimmy couldn’t leave because people wouldn’t stop applauding.”

Geoffrey Young remembered that at the end “the crowd began to clap, and then clap some more, and then not stop but continue clapping, happily, enthusiastically, lovingly, for what surely lasted several long and amazing minutes. [Actually about one minute.] I looked at Ron [Silliman], he looked at me, and together we kept clapping, as did everyone. We’d never seen or heard anything like it . . . It was the palpable and considered and felt response to a man who’d been through a lot, had survived, kept his genius intact, and that evening, in his own voice, delivered a chunk of it to us . . . For which we were unabashedly grateful.”

After the reading, Schuyler and about a dozen friends went to a nearby restaurant to celebrate, where Jimmy, often uncomfortable in that kind of situation, was “in a very good mood, and was very affable.” He left soon afterward to return to his small apartment in the Chelsea Hotel. Two days later he wrote to his friend Anne Dunn with a report of the event, concluding without exaggeration, “I was a fucking sensation.”

Anyone who ever wants to write my biography will have his/her work cut out for her/him, since virtually no documentation or juvenilia exist. There is The Birth Certificate, The First Grade Report Card (F in all subjects: I was a late bloomer), The Passport: and? no diplomas, no degrees, maybe some postcards and a letter or two . . .

—James Schuyler, Diary, August 3, 1985

James Schuyler was one of the five poets usually considered to be the “first generation” of the so-called New York School of poetry. The term began as a joke, and continues as a fiction, but a useful one. John Ashbery, for one, protested against it but Schuyler eventually accepted it as inevitable journalistic shorthand, handy for designating a group of poets who, while certainly no “school” united by any actual or implied manifesto, were close friends and shared a time, a place, a larger circle of acquaintances, and at times a sensibility.

While their poetry was quite distinct, the voices, in prose and sometimes in person, of the four male poets in the group in particular, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, and James Schuyler, could be uncannily similar. Rereading the novel he co-wrote with Schuyler, A Nest of Ninnies, Ashbery claimed not to be able to tell in some cases which lines were his own and which Schuyler’s; while Ashbery’s own mother, listening from another room, once confused his speaking voice with O’Hara’s. The letters that passed among these four share a tone of intimate hilarity, to the degree that the identity of the correspondents can almost seem interchangeable.

I loved hearing him tell stories about his past, which he too seldom did, and I too often failed to remember or to note down.

Rule-proving exceptions frustrate any absolute group identity for the first-generation New York School. Barbara Guest was the only woman. Koch was the only male heterosexual, the only Jew; Guest and Schuyler were the only non–Harvard graduates; in fact, Schuyler didn’t graduate from college at all. Ashbery was the only one of the men who did not serve in the military during World War II. O’Hara died at forty, more than a quarter of a century before any of the others and half a century before the longest-lived of the five (Ashbery). Of these poets, Schuyler may have been the least known for most of his life, for a variety of reasons. Relatively late to publish, retiring by nature, he was plagued by mental illness intermittently, and lived long stretches outside the city. This began to change after the reading at Dia in 1988, and again after his death in 1991 and the release of his Collected Poems two years later. Since then the work has continued to gain new readers, bringing fresh, twenty-first century perspectives, and to sustain longtime ones, who find themselves returning to it again and again.

I had discovered Schuyler’s work in the early eighties and felt a close connection to its directness and lyricism, its wit and music, and, as Ashbery put it in his introduction to the reading, its quality of “inspired utterance couched in everyday terms.” Through my job at an art gallery we had friends in common, and we’d been introduced briefly at a party in 1987. I was excited to be at the Dia reading, but I would never have aspired to know Schuyler if it had not been for two mutual friends, the artists Anne Dunn and Joe Brainard. First Anne brought us together for a quiet restaurant dinner in March 1990, then about two weeks later Joe took us both out to dinner near the Chelsea Hotel, where Jimmy lived.

After the ice was broken I began to see Jimmy on my own; soon we were meeting about once a week, in his tiny apartment in the Chelsea, going out to dinner in the neighborhood or to a movie or an exhibition. Often, we simply spent time sitting quietly together in the two easy chairs that were, aside from a desk, a filing cabinet, and a single bed, the only furniture in his room. I loved hearing him tell stories about his past, which he too seldom did, and I too often failed to remember or to note down. Loving his work, and then him, together and separately, I wanted to know more about how it came about “that he / should grow up to be him,” as he wrote of Darwin in “Empathy and New Year.” When Jimmy died, on April 12, 1991, at the far too young age of sixty-seven, I felt a huge sense of loss, cheated not only of so much poetry that might have been written but also of a close but still new friendship.

Somehow I got it into my head that I wanted to write his biography. When I approached his executor, Darragh Park, with the idea, Park demurred. However, he did suggest I edit Schuyler’s Diary, which I did and which was published by Black Sparrow Press in 1997. To accompany the notes for the Diary I prepared a chronology of Schuyler’s life, and the research I did for this chronology gave me a head start when, six years later, Jonathan Galassi, Schuyler’s editor and the publisher of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, commissioned a biography. Intervening projects and responsibilities have meant that the book took far longer than it might have. Yet having my life entwined with Schuyler’s for so many years has been immensely enriching, and I am gratified finally to be able to present what I have learned to readers, who I hope will find like sustenance in it for themselves.

__________________________________

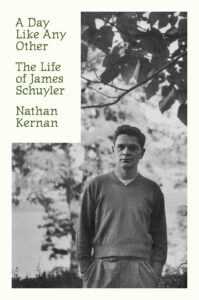

Excerpted from A Day Like Any Other: The Life of James Schuyler by Nathan Kernan. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, a division of Macmillan Publishers. Copyright © 2025 by Nathan Kernan. All rights reserved.