While Tessa Hadley’s The Party began its life as a New Yorker short story, it seems that it wouldn’t, for her, go away. At some point she found herself moved to continue the narrative, and so it became the first of the three chapters of what is now a novella. In my mind, these chapters resemble the mirrors you might find sitting on top of an old-fashioned dressing table, each one providing a different angle, sometimes lovely and sometimes unexpectedly ugly, for the person (the reader) who happens to be gazing into them. The book begins with a party, after all: noses must be powdered, and lips carefully blotted. Only later does anyone notice that the hair on the back of a head has unaccountably become matted, that smudged mascara has darkened pale cheeks.

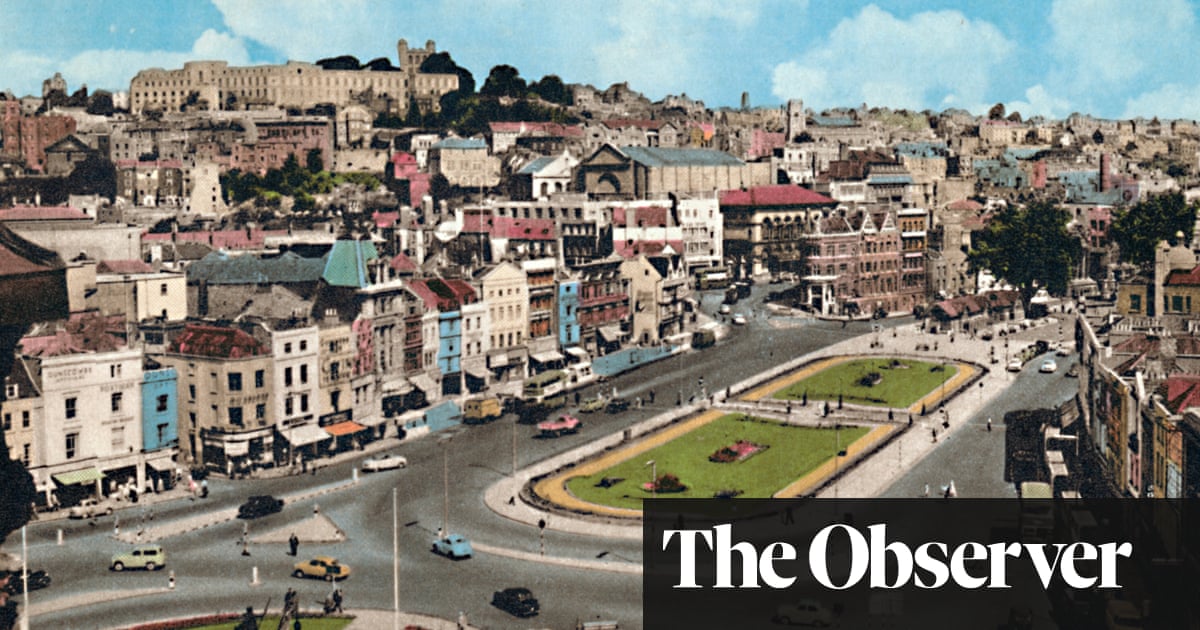

The dishevelment in this story comes courtesy of two men: the sinisterly named Sinden and his friend Paul. At a party in an old boozer in the Bristol docks some time after the war (the Malayan emergency is under way, so we’re talking 1948 or later), these two are loitering rather hungrily when Evelyn, who’s reading French at university, arrives to meet her older and more sophisticated sister, Moira, a fashion student. As the night wears on, neither girl is taken with either of these blokes particularly, but a certain boredom and competitiveness induces them first to drink with them and then to run away from them. Better to get the bus home, they think, than to accept Sinden’s self-proclaimed attempt at “abduction”, however jocular.

But as Moira wisely notes, it’s impossible to get away from “that kind of man”. She and Evelyn survive the party, with its warm gin and undrinkable cider, but Sinden and Paul are playing a longer game, one made all the more easy to win by the sisters’ circumstances. Oh, but the stultification of home! Their parents’ marriage is fractious and fraying. Their science-mad little brother, Ned, is a pest. Both are full of longing: Evelyn for a man she has yet to meet, and Moira for one who’s otherwise entangled. No wonder, then, that when the phone rings at supper time one Wednesday evening, they’re apt to accept the invitation it heralds.

And who, in any case, is going to forbid them this? The finer delineations of class streak this book like the rivulets of water that run down the steamed-up windows when their mother cooks Sunday lunch. The sisters’ putative “friends” Sinden and Paul live in smart Sneyd Park, where they’ve been asked to play mahjong. How nice! Though their father heard a male voice when he picked up the receiver, the man on the other end of the line sounded self-assured. “Don’t spoil your sister’s evening,” he admonishes Evelyn, when she briefly hesitates, suddenly feeling that she’d rather stay at home with Andromache.

In the end, then, Evelyn and Moira do find themselves in a far-off big house, enfolded awkwardly by its posh, rather affected young inhabitants (one of them is called Podge), and over the course of a night, innocence is exchanged for (anti-climactic) experience. What happens, about which I shouldn’t say more here, is moderately shocking in context – though not, perhaps, for the reasons Hadley imagines. I argue somewhat with her notion of the risks middle class young women at the back end of the 1940s might be willing to take in the pursuit of freedom. However, the greater problem by far when it comes to the story’s denouement is her decision to tie up the tale neatly with a bow. Why spell out so explicitly that this night changes Evelyn and Moira? Such emphasis undercuts all that has happened, as if Hadley is suddenly anxious her story has too little weight.

But perhaps she’s right to be worried. I’ve always loved Hadley’s books, her earlier novels (The London Train, Clever Girl) particularly; at her best, she has something of Elizabeth Taylor about her (there is no higher praise). More recently, though, something new has crept into her writing: a self-consciousness that has her overstuffing her sentences with adjectives (“the small, slack breasts with their dark spreading nipples were derisory, insulting”) even as she’s happy to deploy cliches (here, she writes of bombed-out Bristol’s “broken-toothed skyline”).

It has, I think, to do with her move backwards in time: she’s so much less comfortable as a writer in the past than in the near-present, and in this book, as in her previous novel, Free Love, the historical details are often unconvincing, too generic truly to be felt. If the story’s more shocking events strain for effect, so do the quotidian details: the laboured descriptions of clothes, music and (especially) food. The novella’s scantness should deceive; it is a form whose punch should feel disproportionate, even a little dangerous (think of Mary Gaitskill or Claire Keegan). But this one is too slight, and too underpowered: a strangely watered-down thing, not heady enough even to leave you with the whisper of a hangover.