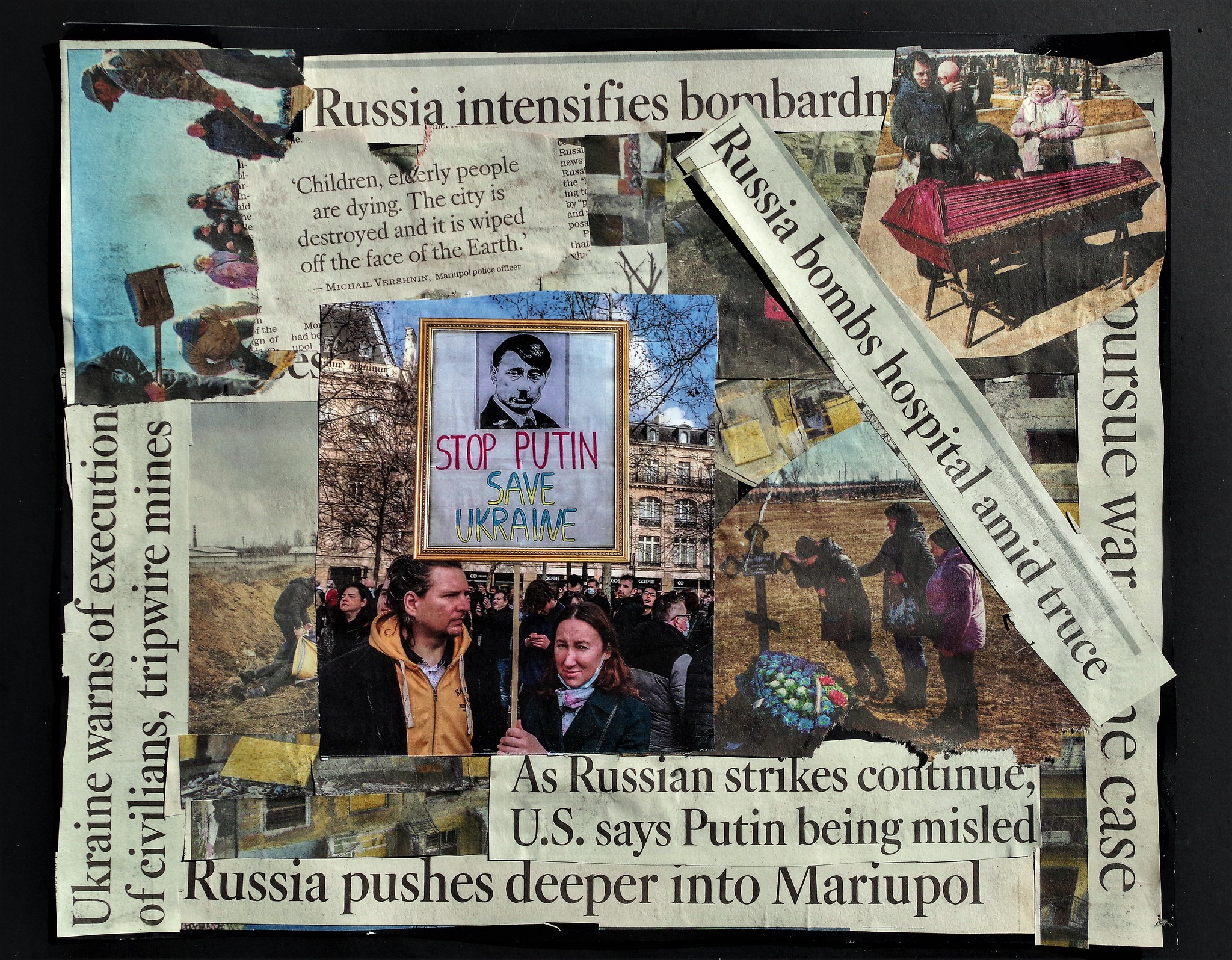

Why would Russia invade Ukraine? Geopolitical strategy, economic motivation, and ethno-racial or religious hatred—explanations currently on offer to make sense of Russia’s brutal campaign of destruction against its neighbor—fall markedly short of providing satisfying answers. What we are witnessing, and what murders and maims thousands, is a war of unusually pure propaganda, in which tanks and bombs are subordinate to bizarre rhetorical turns.

But what does the propaganda serve? It seems little other than its own reproduction. In the process, the form of propaganda itself appears to be disintegrating. Narrative coherence becomes irrelevant. Fake news—which retains the form of journalism, if not the content—is too real to be useful. Indeed, this propaganda hardly persuades anyone. Persuasion, however, is not the objective but, in fact, a distraction. In this and so much else, then, Russia’s brutal, unprovoked aggression may be the clearest manifestation of “postmodern war” the world has yet seen.

Russia’s war reflects a tide that has been rising across the globe and drowning out long-taken-for-granted political forms. In their place has emerged a dysmorphic, dysplastic, and dystopian politics without ground, stable meaning, or substantive objective. Against such politics, traditional modes of both analysis and resistance are largely futile. The rise of dyspolitics, as we propose to call it, long preceded Russian’s invasion of Ukraine, which provides a case study of its functions.

Dyspolitics is not about distractions, deflections, or diversions. It is instead an operation of substituting the constitutive elements of politics so as to remake the perception of the political itself. By this means, it is intimately linked to the dismantling of the notion of the public good. The corrosion of the public, in turn, affects citizens’ perception of themselves and their own capacity for a political life that might enact and ensure a democratic commons.

And dyspolitics is hardly confined to Russia. In the internet age of informational superfluity, the spectrum of dyspolitics can vary from marginal delusions of “pizzagate” to more mainstream, enduring expressions, such as the fantastical tropes that have circulated around Mexicans and Trump’s border wall, the so-called Muslim ban, or the invention of the Space Force. Alt-right venues—where the “alt” most accurately reflects an alternative to a shared empirical reality—like QAnon, 4chan, Trump’s social media accounts, InfoWars, and Fox News provide ready examples of both peddlers and symptoms of American dyspolitics from the Far Right. But liberal discourse is growing strikingly similar, as we can see under Biden during ongoing US-enabled Israeli massacres of Palestinian civilians in Gaza. Take, for example, the characterizations from the White House, New York Times, the Atlantic, or MSNBC of peaceful, often-Jewish-led antiwar protests as “antisemitic” movements that must be repressed by police or the redefinition of children, doctors, and poets in Gaza as “terrorists” or “human shields” whose extermination is deemed a perhaps tragic but nonetheless necessary task.

Dyspolitics effects a dematerialization of the political, but that does not mean it is without material consequences. To the contrary, it often utilizes direct violence. And what makes it especially pernicious is that it can be appropriated by proto-fascist and liberal regimes alike, compelling us to ask: Was there a difference here to begin with? It does so by redefining politics not as a matter of the distribution of wealth, rights, nor either negative or positive freedoms but instead as infinite war against an imagined degenerate enemy who threatens to inflict national dystrophy and from whom the metaphysical nation—conjoined, in Biden’s case, with a dematerialized notion of “democracy” in which he is savior—must be protected.

In this process, dyspolitics uproots the political from any stable ground and puts it out to sea. There, it moves with the tides as politics slowly disintegrates into an ever-shifting milieu in which the differences upon which genuine democracy depends can now only clash. Dyspolitics makes war without end into an overarching political paradigm.

dyspolitics might be understood as an episteme against epistemology: an apparatus for designating not the true, the scientific, nor any enduring knowledge at all, but rather an insistently nihilistic form of politics.

A precise origin of dyspolitics is impossible to locate. Still, evidence of its presence—often optimistically dismissed as nothing but farce—has been increasingly discernable in Russian media for several years. To understand Russia’s war in Ukraine, and what it can teach us about our global political present, we must look beyond obsessions with Putin to the disintegration of political discourse upon which he now rides.

One year before the first tanks crossed from Russia into Ukraine, an authoritative independent Russian newspaper, Novaya Gazeta, published a piece with an ambitious title: “Похищение Европы 2.0 Манифест режиссера” (“The Abduction of Europe 2.0. A director’s manifesto”). The author, Konstantin Bogomolov, is a celebrated contemporary theater director and an icon of the culturally progressive local public.

In feverish language well-suited for wartime, the article condemned “the West” for the “evils” of multiculturalism, feminism, Black Lives Matter, etc. This emerging society, warned Bogomolov, was no less than a “new ethical Reich”; he even condemned progressive activists as “new stormtroopers.” Although Russia had not previously been an ethical nor aesthetic ideal for Bogomolov, he now likened the nation to the “last car” in “the crazy train heading towards the Boschian hell, where it will be met by multicultural gender-neutral demons.”

Fortunately, he reassured his readers, Russia still retained a chance to unhook itself from the doomed locomotive. Once free from the West’s evils, he said, Russia could embark on a home-grown project nurtured by “a new right ideology … anchored in a complex man.”

One could easily dismiss this as a vapid, provocative text by a self-fashioned enfant terrible. But, in fact, Bogomolov’s manifesto fell within the mainstream of public discourse in prewar Russia. Such sentiments were echoed by much-publicized political statements about the Russian “deep people” by Kremlin political strategist Vladislav Surkov or about the “Russian genetic code” by Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov.

Few Western observers took such rhetoric seriously. But within a year, a bizarre call to “de-Nazify” Ukraine became Putin’s casus belli. In short order, Bogomolov’s theater struck an official partnership with Russia’s main propaganda outlet, RT. Soon, hundreds of thousands of Russian citizens were marching across the Western border to kill people in neighboring Ukraine. What began as absurdist farce became violent tragedy for millions.

We highlight Bogomolov’s text because, precisely in its mediocrity, it reflects a dangerous trend. Increasingly, a language of civilizational meta-realities—take, for example, ubiquitous Russian references to “state-civilization,” “deep people,” “traditional values,” or “cultural code”—is displacing comprehensive visions of socioeconomic organization that have served as grounds for conventional modern politics in Western liberal democracies and the Soviet sphere since the end of World War I.

Over time, rhetorical absurdities have helped redraw the parameters of the political (that is, what constitutes the perceived terrain of politics, of political action and contestation). Rather than attempting the Sisyphean task of reconstructing a coherent ideological program out of such statements, we can look at the functions these dystopian languages serve. In this respect, the omissions and silences in these narratives are often more telling than their stories.

Bogomolov’s article appeared a week after the Moscow City Court substituted a suspended sentence for a real prison term for Alexei Navalny, who returned to Moscow after surviving a Novichok poisoning. In parallel, Navalny’s team released an investigative documentary about “Putin’s palace,” exposing a striking scale of alleged corruption, which instantly became one of the most widely watched videos of the Russian-speaking internet.

Domestic and foreign commentators expected popular protest to build to potentially explosive levels, due to the combination of accumulated discontent associated with the coronavirus pandemic (as the Russian state had prioritized the preservation of financial reserves over basic assistance for its population); constitutional amendments to “nullify” term limits on Putin’s presidential reign; and a seventh year of declining or stagnating real incomes.

The scale of the eventual two-week protests that rallied around Navalny was significant. But they remained within the margins of other mass mobilizations of the last decade and waned soon after confronting disproportionately violent police suppression.

All these events were conspicuously absent from Bogomolov’s essay. As he commented later, the civilizational issues he was dwelling upon were of far greater importance for him relative to “concrete cases of inadequacies of state power.”

A year later, Putin declared full-scale war on Ukraine. As he did so, Russia’s leader was similarly disinterested in the realities on the ground. In place of such realities, he drew constant bizarre parallels to World War II, while also condemning US hegemony and its undermining of supposed Russian values.

Nine months later, addressing the mothers and widows of Russian soldiers killed in action, the Russian president consoled them by reminding them about the inevitability of death, and assuring them that to die in war is a more meaningful way to die than “because of vodka.” And Russian society has, on the whole, remained passive in the face of mounting death tolls. Large-scale protests have failed to materialize. Small islands of resistance have been swiftly stifled by draconian legislation. Thousands have obediently joined the ranks of the occupying armed forces. And unlike during prior armed conflicts in Afghanistan and Chechnya, there has been no significant organized movement of soldiers’ mothers to oppose the war.

In a prewar interview, echoing both Bogomolov and Putin, Sergey Lavrov explicitly denied that the state’s focus should be sustaining citizens’ well-being. The minister bemoaned the “narrow, lopsided view” of those criticizing Russian state politics for its negative consequences on the standard of living. He suggested that these people were undermining the Russian “genetic code,” which allegedly embraces the importance of the “feeling of national pride,” to which the desire to “live well” should be sacrificed.

Dyspolitics provides cover for the deepening of neoliberal policy violence, which enforces material deprivation on workers, racial and religious minorities, and the variously dispossessed.

Lavrov’s words reflect the stakes of politics as envisaged by the Russian leadership: Unlike the Soviet state, contemporary Russia does not aspire to offer an alternative universal model of social organization. The current ideal, instead, draws on a geopolitical imagination that establishes Russia as a metaphysically enclosed subject unto itself.

There are many immediately obvious material-political problems facing Russia, on which all these commentators continue to remain silent. Instead, their language reaches for the distant, dematerialized, and dystopian. Such simultaneous indifference to reality and embrace of fantasy is a hallmark of dyspolitics.

By redefining the scope of politics in the process, dyspolitics might be understood as an episteme against epistemology: that is, an apparatus for designating not the true, the scientific, nor any enduring knowledge at all, but rather an insistently nihilistic form of politics. It does so by expressly refusing criteria for ideological systematicity or coherence, while disengaging from the concrete realities of people’s lives.

Dyspolitics operates through dematerialization of what constitutes the political, displacing political economy from that which can be contested at all. In so doing, it provides cover for the deepening of neoliberal policy violence, which enforces material deprivation on workers, racial and religious minorities, and the variously dispossessed. It does so by shifting the terms of debate and posing as the last defense against the deterioration of society and existential threats posed by corrupting external and internal enemies.

The resulting undelineated state of emergency inaugurates unchecked and extrajudicial practices of violence, from drone killings and assassination of dissidents to campaigns of mass brutalization and genocidal massacres.

Such political frameworks are well known the world over and are far from new. One prominent form they have taken in the historical centers of liberal-neocolonial capitalism is “the clash of civilizations” thesis associated with Samuel Huntington. This dyspolitical formation has found bipartisan American endorsement as “the war on terror” against “the axis of evil” launched by George W. Bush, which has been perpetuated under every subsequent US administration up to the present. Variations on this theme have, in turn, been widely embraced by allies operating in dyspolitical Islamophobic and xenophobic coordination in the UK, France, Germany, Israel, India, and elsewhere—as is reflected by collective support by these nations for the ongoing Israeli violence in Gaza.

Civilizational frameworks are but one possibility for dyspolitics, however, which can just as easily make do with bizarre conspiracy theories about invented devils. These need not have the internal coherence of proper myths or historical traditions. The pervasiveness of the dyspolitical relies not on the power of persuasion, indoctrination, or plausibility, but on supplying rhetorical categories, shifting agendas, and tacitly redefining the terms of political engagement.

Dyspolitics is not the exclusive purview of militarism. In rough historical terms, contemporary dyspolitics in its American variations could be understood as a radicalization of “the culture wars,” which gained influence with the rise of the evangelical Right in America as a culturalist corollary to the Cold War. Consider the sexual paranoias that circulate around gay and trans rights and Roe v. Wade, or anti-Black animus in the aftermath of school integration and the civil rights movement, which found expression in the racist “war on drugs” and the construction of mass incarceration.

After 1989, with the ascent of neoliberal models as the supposed only option after “the end of history,” these culturalist dynamics were increasingly untethered from a materialist backdrop for perceiving and engaging with the political. As an emergent dyspolitics in the US became increasingly detached from an explicit economic ground, it was freed to locate and perpetuate itself through cults of identity, moral condemnation of conservative “deplorables,” and celebrity that may have reached its zenith with President Obama. Under Obama, who was tellingly succeeded by a reality-television star, the US enjoyed an executive whose administration was premised on an ostensibly progressive personality cult while his political-economic ideology was largely an echo of the neoliberal commitments of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

When Thatcher was asked in 2002 what she regarded as her greatest achievement, she famously replied: “Tony Blair and New Labour.” In the same way, Clinton, Obama, and now Biden—not the Republican politicians who fight to carry Reagan’s mantle—may be the truest descendants of Reagan that we have known.

The question of the political asked from Russia—that is, from outside the dominant, ready-made terms of criticism that center Western Europe and the US—is useful not because the Russian scene is altogether unique or original. It is not. Instead, the Russian vantage, if not reduced to the personality of Putin, recasts what has become so familiar and correspondingly muddy in ubiquitous debates about the rise of fascism and reductive obsessions with the authoritarian personality that have permeated political discourse since the election of Donald Trump.

What is most important about dyspolitics is not its contingent leaders or content (e.g., Putin and other figures in Russia, Trump or Biden, migrants, white supremacy, Muslims, Mexicans, Black Lives Matter, etc.) but the structure of a political meta-reality that abstracts a reified collective moral self from materialist grounds and situates politics as a free-floating relation to the threat of categorical others. This structure of dyspolitical formation is just as easily adapted for use by ostensible emissaries of liberal progressivism as it is by the alt-right.

Structural analysis of contemporary Russian politics exposes how political spheres are effectively reconfigured by an essential pairing of dyspoliticization with corollary depoliticization. The synergistic relation between dyspolitics and neoliberal policy should push us to recognize that the lines of political struggle are never—and perhaps least now than ever before—reducible to predetermined monolithic terms by which history simply repeats itself. As different dyspolitical currents circulate across spaces, they operate via mutually reinforcing international correspondence with one another while also always inflected by particular contestations fought on multiple, simultaneous, often contradictory, and always historically specific grounds.

Historical analysis is indispensable for attempts to understand and act in the present. But continuing to invoke precedents and parallels from earlier political epochs—as if the political task of today is simply to repel the fascisms of yore—is insufficient and, without grounding in the political economy and lived material realities of today, may even deepen the dyspolitical crisis through which we are now living. ![]()