I encounter Liza for the first time while researching her husband, Oleg Dal, an actor who specialized in playing misanthropic men.

Article continues after advertisement

Oleg met Liza Apraksina in 1969, on the set of a King Lear adaptation. He was playing the Fool, and she was a film editor who cut the celluloid and assembled it into scenes. Actors wandered in and out of the editing room to watch the footage that had been shot that day. Oleg’s jester was an ethereal, emaciated sage; the film’s director said he looked like “a boy from Auschwitz.”

Liza was entranced by this man with high cheekbones and a haunted gaze. She was already being romanced by the writer Sergei Dovlatov, but when both men came to her family’s apartment, it was Oleg whom she asked to stay the night.

Oleg and Liza came from different worlds. He was the son of a schoolteacher and an engineer who hailed from Moscow’s industrial outskirts, while she was born to the old literary intelligentsia in Leningrad. She grew up to work at Lenfilm, one of the Soviet Union’s top studios.

Marx and Engels had seen the family as a site of exploitation and thought it should be destroyed together with private property. After the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks made men and women equal in law, and feminist Alexandra Kollontai called for the public raising of children and open relationships.

The prospect of female emancipation aroused anxiety among a political establishment that was still almost entirely composed of men.

But the prospect of female emancipation aroused anxiety among a political establishment that was still almost entirely composed of men. Under Stalin, the Soviet women’s department was disbanded, and the “woman question” supposedly resolved.

By the 1960s, after Stalin’s death, women had entered the workforce in record numbers, but stayed at the bottom of the ladder and continued to do most of the labor at home. The state did not tolerate any serious criticism of their inequality—purportedly a bourgeois Western problem. According to sociologists, exerting a proper feminine influence would keep irresponsible husbands in check and reinvigorate their flagging masculinity.

In her letters, Liza dubbed Oleg “your eminence” and extolled his growing fame: “Everywhere I hear: Dal, Dal!” He played her his favorite Coltrane records and told her that she relieved his sadness.

“I predict you will experience incredible torments with me,” he wrote to her in a letter. “But love me! I need you. I need your shoulder; for I am a poor fellow [bedolaga] and a spineless madman.”

*

Moscow, summer 1977. Liza catches the B bus on her way home. White puffs waft through the air in the late afternoon sun—fluff from the poplar trees that Stalin planted around the city. Every June they unleash millions of seeds that float on the wind like summer snow. One of them lands in her brown hair, and she brushes it off as she steps aboard.

She is carrying the collapsible string bag that she keeps with her in case of an impulse purchase. If sausage is in the shop today, it might be gone tomorrow. Today the bag is bulging with chanterelles, which have just begun to appear at the market.

Liza feels faint in the heat. She recently read that Chekhov, a medical doctor as well as a writer, advised consuming as little as possible to preserve one’s health. To manage cravings, he suggested drinking a glass of milk, which is the only thing that she has had today.

Oleg barely eats at all. She realized how thin he was the first time he showed up in the editing room, bones visible beneath his skin in a frame as light as poplar fluff. It is her duty to keep him from blowing away.

The doors close and a network of electrical wires propel her forward around the ring, past the triumphal arch that marks the entrance of Gorky Park. The canals of her childhood were winding and intimate; she can’t get used to Moscow’s superhuman scale.

As the trolleybus heaves across the suspension bridge that straddles the banks of the Moscow River, she sees the golden domes of the Kremlin glinting on the river’s edge. The bus hurtles on until she pulls the cord and it comes to a halt at Smolensk Boulevard.

Their apartment walls are covered with bookcases and photos of Oleg. Among them is a charcoal sketch of Liza’s face, scribbled by an artist when she was a child.

She tosses the chanterelles into a frying pan. As their orange bells collapse in the oil, she starts running through the familiar list of questions. What kind of mood will he be in tonight? Will he be drunk? Mean drunk or happy drunk?

If he’s mean, she reminds herself that she must not cry. Oleg hates whining. In fact, if he seems unhappy, it’s best to give him an excuse to blow up at her. If he yells, if he throws something, that’s good—the tension has released. Allowing it to build up is much worse. Anxiety creeps under the door and through the windows like mustard gas.

At last Oleg walks in, fresh off his flight from Prague, where he traveled with an official delegation from the Soviet film industry. He has brought back a bottle of slivovitz and is wearing a new pair of shoes. The Czechs live like gods, he says. Last night there was a farewell banquet, but to her surprise he doesn’t seem hungover.

When I read Liza’s lines about Oleg, or my own texts with my ex-boyfriend Daniel, I hear the echo of an echo.

The whites of his eyes are clear, his spirits are high, and he’s not asking for a drink. The gas dissipates, and Liza starts to breathe. As they sip coffee with slivovitz, she dares to ask whether he might consider getting an esperal implant—a device that blocks the metabolization of alcohol, producing a severe and near-immediate hangover meant to discourage drinking.

He says he will; she is overjoyed. After he lays down to sleep, she writes her mother a jubilant update: “He’s nothing like he was then.”

A few days later, she sends another letter: “It was bad—terrible depression, fear, etc.”

Weeks later, one more: “Olezhechka,” she writes, using an affectionate diminutive of his name, “is sweet as always.” She signs off as a collective unit:

“Kisses, us.”

*

Their relationship continued until March 3, 1981, when Oleg died in a Kyiv hotel room of a heart attack. Liza told a reporter that “it seems to me as if I was burned and buried too and only some fragment of me remains in this world….It’s what all lovers dream of, dying on the same day.”

She spent the next two decades preserving their apartment as a shrine. More and more photos of him appeared on the walls, until the drawing from her childhood was the only female face in a phantom army of Olegs. She corresponded with his fans and wrote to the Ministry of Culture demanding that more be done to promote his legacy.

When Liza died in 2003 at age sixty-five, her remains were cremated and laid in the ground next to his. A short article about her in a Russian tabloid ended with a list of Oleg’s best films.

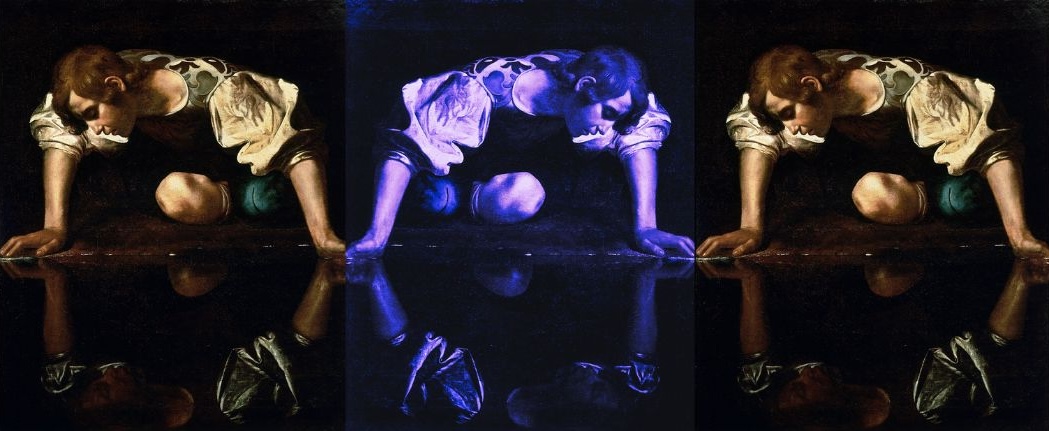

The Greek nymph Echo, who is doomed to parrot the words of others, gazes at Narcissus as he beholds his reflection in the pool. When I read Liza’s lines about Oleg, or my own texts with my ex-boyfriend Daniel, I hear the echo of an echo. I recognize the underlying tension in Liza’s reassurances, her awareness that Oleg could flip at any moment, the constant monitoring that she thinks is care for him but is also an instinctual safeguard for herself.

These men speak and speak, and demand we listen and repeat. Rather than allowing the sounds to fade away, I long to combine them and raise the volume until they form a resonant chord, so loud it drowns out the original source.

______________________________

A Survivor’s Education: Women, Violence, and the Stories We Don’t Tell by Joy Neumeyer is available via PublicAffairs.