Chesterland, Ohio, 1979

Article continues after advertisement

I’m six years old and watching my two older brothers roll dice on the orange linoleum tiles in the basement. If I move a muscle, I’ve been warned—if I speak so much as a single word—my banishment to the upstairs will be reinstated.

Mark, our middle brother, crouches behind a cardboard screen. “You find yourself,” he says, “in a long corridor.”

A corridor! That word! In our house we only have hallways: one hallway, actually. But here, in the wizardry of the basement, are corridors.

“You reach a staircase. You can go up or down.”

Our eldest brother, Chris, scrutinizes a yellow sheet of paper. “We go down.”

Dice roll behind Mark’s screen.

“You enter a room paneled in gold. As soon as you step inside, the door slams behind you. Ahead, you see a chest with a ruby set in its top.”

The cities are stars, the sections constellations, the book a galaxy, and Calvino’s structure allows a reader to study each star and admire its idiosyncrasies.

“We take the ruby.”

“It won’t budge.”

“We open the chest.”

More dice.

“Inside is what looks like a quivering black pudding.”

Chris’s wizard and warrior, who live, apparently, inside yellow sheets of paper, attempt to dump out the pudding to see if there is treasure beneath, but the pudding comes to life! It divides into multiple puddings; it snuffs their torches; it begins to eat through their armor.

I creep forward, desperate to peer behind the screen. I want to see the raging battle, the terrible ooze. But all Mark has back there are a couple of tables of numbers and four sheets of graph paper absolutely covered with a pencil labyrinth. Does the graph paper contain the golden room, the ruby and the chest, the guardian slime?

Chris’s characters are dying; they need to make a run for it. But there’s no way out.

“We search,” he says, “for secret doors.”

More dice.

“You find one.”

*

Novelty, Ohio, 1994

I’m twenty. I dream of becoming a story writer but have no idea how a dream like this becomes real. One day my science-teacher mom hands me a collection of stories called Cosmicomics by an Italian writer named Italo Calvino.

On the first page, a protagonist named Qfwfq remembers a time when the moon was so close to Earth that, at high tide, he could row out in a boat, prop a ladder against the lunar surface, scramble up, and harvest cream cheese. Qfwfq falls in love with Mrs. Vhd Vhd, who loves Qfwfq’s cousin. The story ends with Mrs. Vhd Vhd permanently stranded on the moon. “I still look for her,” Qfwfq says, “as soon as the first sliver appears in the sky.”

In the following story, set at the dawn of the universe, Qfwfq’s sister vanishes inside the still-forming core of the Earth; he does not see her for a few billion years, until he finds her “at Canberra in 1912, married to a certain Sullivan, a retired railroad man.”

Wait. What? The stories I’ve committed to paper thus far involve a poker game and amorous encounters between dog walkers. My characters have names like Ray. And here’s this guy Calvino naming characters Qfwfq and Kgwgk and writing sentences like, “I’ve been in love for five hundred million years.”

The last story in Cosmicomics is narrated by a mollusk.

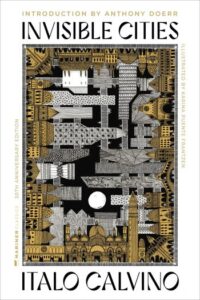

I drive to a Waldenbooks in a mall and buy Invisible Cities, a 165-page paperback inside which, according to the jacket copy, the Venetian traveler Marco Polo tells his boss, Kublai Khan, emperor of the Tartars, tales about a bunch of cities he has visited.

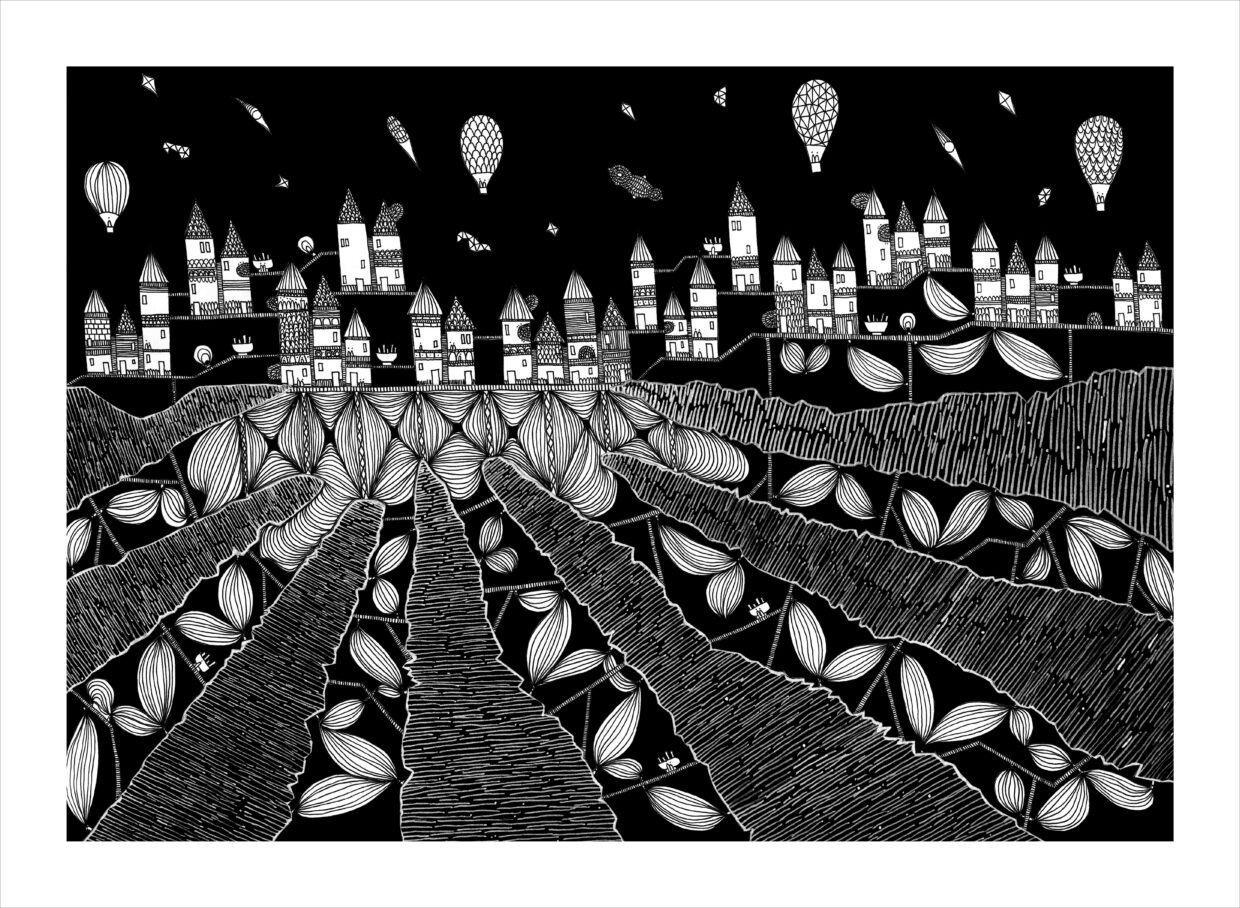

By page 13, the book feels like a sorcerer’s travelogue dipped in a vat of psilocybin—a Lonely Planet in which all of the destinations are imaginary and none of the directions make any sense. To reach the city of Tamara, for example, all you have to do is “walk for days among trees and among stones.” To get to Euphemia, simply proceed “eighty miles into the northwest wind.”

Is this a novel? The jacket copy is noncommittal. Each city’s description arrives on a fresh page as though it were a chapter, but I can’t identify any this-happened-then-this-happened relationships between them. There’s no hierarchy either: this isn’t a “Top Fifty Cities of Your Kingdom” listicle.

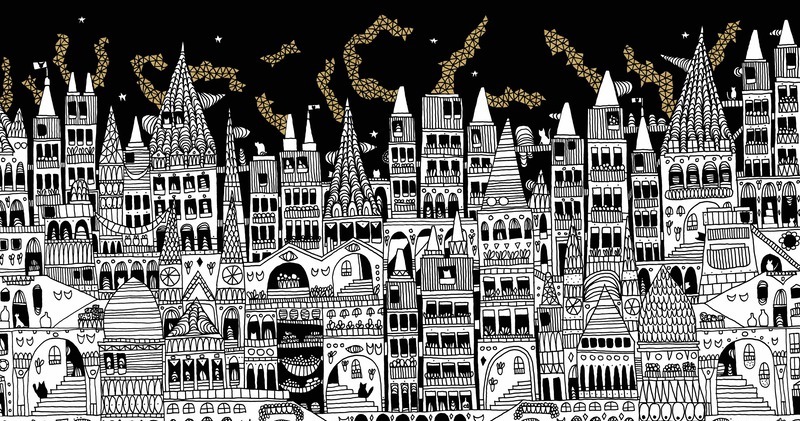

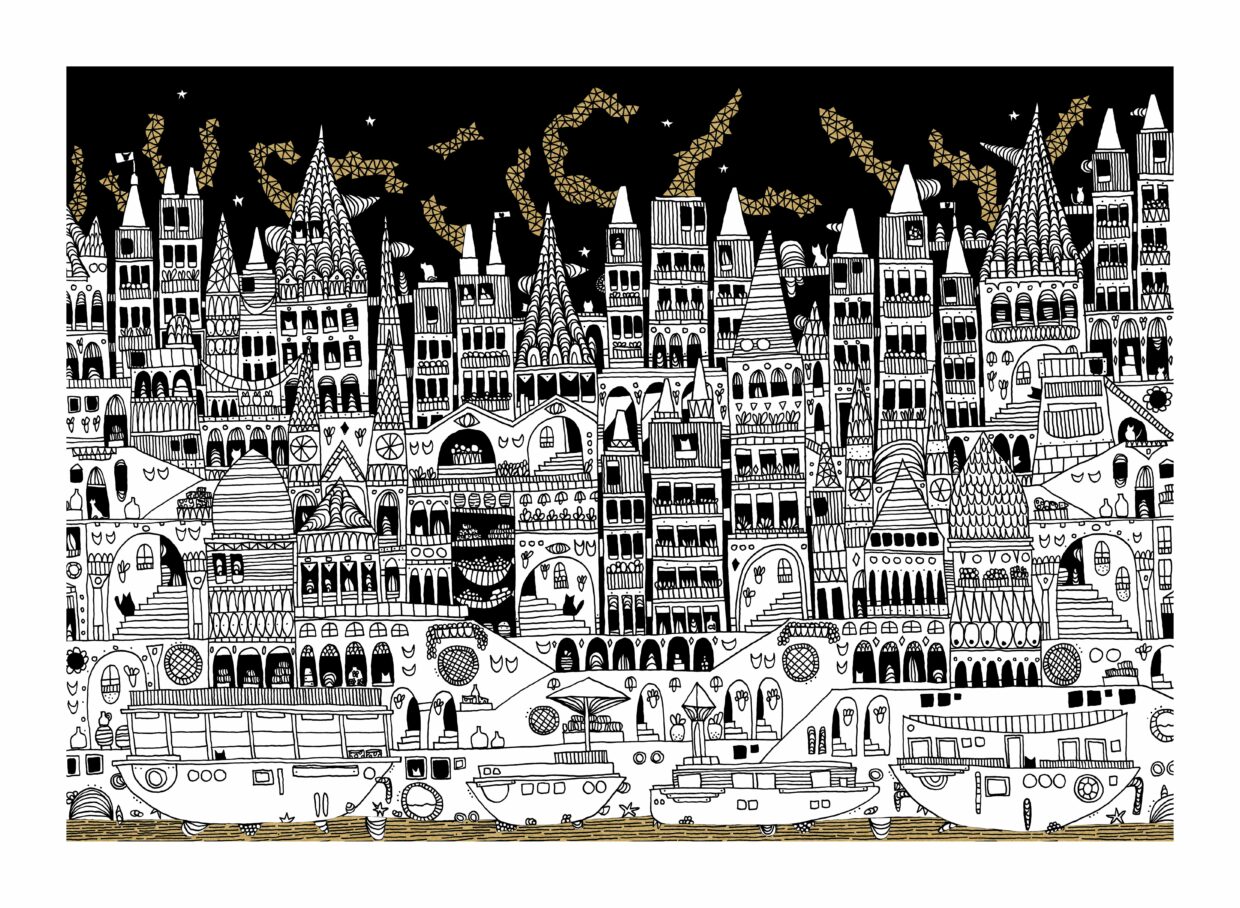

I slow down. I arrive at Isaura, city of a thousand boreholes, where “the gods live in buckets that rise, suspended from a cable, as they appear over the edge of the wells.” Fifteen pages and several days later, I’m in Zenobia, city on pilings, “with many platforms and balconies placed on stilts at various heights, crossing one another, linked by ladders and hanging sidewalks, surmounted by cone-roofed belvederes.” The beauty electrifies. The breadth of Calvino’s imagination dazzles—I see his cities with the same hallucinatory clarity that I saw my brothers’ dungeons in the basement. But I can’t divine any pattern connecting them.

I think: You’re allowed to do this?

I think: I have a lot to learn about writing.

*

Bowling Green, Ohio, 1999

I’m twenty-six. I’m still writing stories built on traditional narrative frames. Rising action, climax, denouement—my characters toil up the slopes of Freytag’s Pyramid. I have become semi-miserable writing this stuff.

One morning I walk to the university library seeking magic. The only Calvino they have is Invisible Cities. I carry it to a carrel; I try again.

Only in Marco Polo’s accounts was Kublai Khan able to discern, through the walls and towers destined to crumble, the tracery of a pattern so subtle it could escape the termites’ gnawing.

By the time I reach Dorothea, city of four aluminum towers and seven spring-operated drawbridges, elation is surging through me. As before, Calvino’s hallucinatory imagination bowls me over. But this time I also glimpse patterns. An architecture does bind this book—I was just too inexperienced to recognize it before.

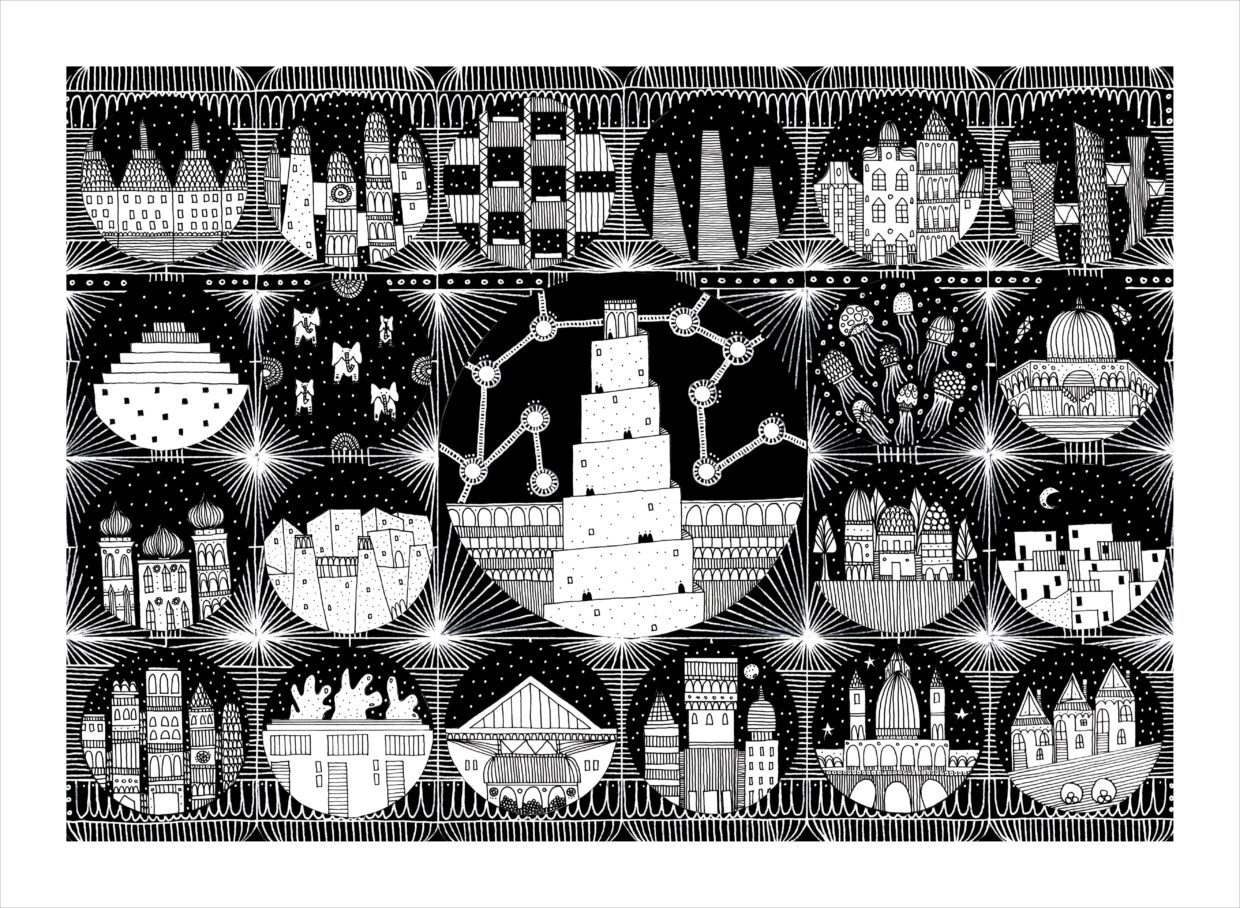

I diagram the table of contents, drawing lines between cities and eyes, cities and names, cities and signs. The text contains fifty-five cities in nine sections; the first and last sections contain ten cities each; each city falls under one of eleven different categories. What do the descending numbers after the categories mean? Would it be possible to plot the cities on a chessboard? Or as a Fibonacci spiral?

It strikes me that Calvino’s blueprint must lie in dualities, as in the city of Valdrada, where everything that happens in the city itself is reflected in the lake it perches above. Or possibly, like the spiderweb city of Octavia, the strands connecting Invisible Cities stretch in a latticework strung between two high points, and “all the rest, instead of rising up, is hung below.”

Six years earlier, it took me weeks to wind my way through Calvino’s cities. This time I whisk through them in a few hours. I draw lines, plot numbers; I feel as though I’m about to find a secret door. Has a book ever filled me with such a sense of possibility? The cities are stars, the sections constellations, the book a galaxy, and Calvino’s structure allows a reader to study each star and admire its idiosyncrasies, while it simultaneously allows him to develop a mysterious, dark energy in the negative spaces between stars.

Like the Great Khan, I’m sure that I’m “on the verge of discovering a coherent, harmonious system underlying the infinite deformities and discords.” If I try a little harder, I believe that I’ll find the key. I’ll identify the one stone in the arch that holds up the bridge.

*

Boise, Idaho, 2024

I’m fifty. I reread Invisible Cities for the fourth or fifth time, a book published fifty years ago, when Calvino was also (almost) fifty. I will finally be old enough, I think, to solve the riddles of this book.

Once again I find myself enchanted and bemused. “I could tell you how many steps make up the streets rising like stairways, and the degree of the arcades’ curves, and what kind of zinc scales cover the roofs,” Polo says about the city of Zaira. “But I already know this would be the same as telling you nothing.”

The more we arrange language in certain patterns, Calvino seems to suggest, and the more those patterns become familiar to us, the less clearly we see the images they’re meant to evoke. Like the towering mountains of trash that accumulate around the city of Leonia, language grows heavy and ineffectual through overuse. Yet language is the only tool Polo has. This is the great paradox of storytelling. We are left banging around on pots and pans, as Flaubert suggested, while we long to make music that can touch the stars.

The Khan, eyes half-lidded, yearns for his emissary to lift away the encrustation of familiarity. “On the day when I know all the emblems,” he asks Marco,

“…shall I be able to possess my empire, at last?” And the Venetian answered: “Sire, do not believe it. On that day you will be an emblem among emblems.”

At the heart of Calvino’s glittering, whimsical humaneness is an adoration for the materiality of life, for cities “crammed with wealth and traffic, overladen with ornaments and offices.” Yet he equally adores the gossamer lightness of the imagination: “cities transparent as mosquito netting, cities like leaves’ veins, cities lined like a hand’s palm.” And he delights most of all in traveling the space between the two.

It’s a fool’s errand, I know now, to attempt to pinpoint a single schematic underlying everything in Invisible Cities—or in life, for that matter.

You cannot read Invisible Cities in the modern era and not think about the ways the internet and social media have transformed travel. Maybe, the very first time you tiptoed out onto the feeds, you felt like an emperor, strolling out from beneath a silk canopy to survey a gleaming, multicolored empire. But, very likely, before you’ve finished your first hour on the infinite scroll, your kingdom, “which had seemed to us the sum of all wonders,” has started to become “an endless, formless ruin.”

Social media, as critics like Jenny Odell have pointed out, has no finish line. On the internet, we are all emperors, trying and failing to “possess” our empires at last. Limits give our lives—and our works of art—meaning. The limits of language, the limits of memory, the limits of our bodies, the limits of a single book to contain all possible worlds: these boundaries produce beauty because they produce finitude. And to be finite is to be human.

*

About Invisible Cities, Calvino would later write, “It became clear to me that my pursuit of exactitude was forking in two directions: on one hand, the reduction of incidental events to abstract schemes that could be used to perform operations and demonstrate theorems; on the other, the effort of words to convey as precisely as possible the perceptible aspect of things.”

It’s a fool’s errand, I know now, to attempt to pinpoint a single schematic underlying everything in Invisible Cities—or in life, for that matter. The wizardry lives both inside the pencil-drawn maze on the graph paper and inside the ever-expanding and contracting space between brother and brother, between Marco and the Khan, between Calvino and you, dear reader.

A great work of literature is a city we can return to throughout our lives, and each time appreciate different sights. My advice is to let this book be whatever it needs to be to you at the time you open it. Visit each city; admire its sights; note the mysterious power that builds in the gaps between. Trust its shape even as it resists your attempts to delineate it.

I finish Invisible Cities and reread Polo’s reminder to recognize and support “who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno.” I step outside and a scent in the wind sends me winging back to an Ohio basement forty-four years ago.

As I grew older, my brothers let me create my own characters and join their game. Sometimes they bought premade dungeons for us to explore, but on the best days we wandered worlds of our own creation. To participate in an act of cooperative imagination—as my brothers and I did those summer afternoons; as every reader and writer do, every time a book is opened—was everything I longed for. We sat in a basement in Ohio on orange linoleum tiles; we simultaneously traveled invisible cities.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Invisible Cities [50th Anniversary Edition] by Italo Calvino. Reprinted with permission from Mariner Books, a division of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 1972 by Giulio Einaudi Editore. English translation copyright © 1974 by Harcourt, Inc. Introduction copyright © 2025 by Anthony Doerr. Illustrations copyright © 2025 by Karina Maria Puente Frantzen.